A. K. M. Adam

andrew.adam@theology.ox.ac.uk

Abstract

The single greatest impediment to clarity in hermeneutics arises from the intuition that words have meaning as a property. This essay will show an alternative to the hermeneutics of subsistent meaning, displaying a way to think about hermeneutics as an interplay of expression and apprehension. By learning about “meaning” from the more pervasive phenomenon of inference and apprehension and reasoning toward language as a special case — rather than beginning from language (which harbours subsistent “meaning”) and treating other patterns of apprehension as “the language of music,” “the language of flowers,” and so on — we can articulate a hermeneutic that better explains interpretive difference, and provides ways to evaluating interpretive claims outwith the customary bounds of exegetical correctness.

Keywords

hermeneutics, interpretation, visual exegesis, information design, comics theory, Magritte, Tansey, differen- tial hermeneutics

At the intersection of intuition, criticism, translation, Whiteness, patriarchy, print technology, and various other pathways of discourse — some honourable and praiseworthy, others louche and enticing, and still others pernicious and toxic — grows the familiar shrubbery of meaning. ‘Meaning,’ that is, in the sense of a quality that subsists in words and phrases, with reference to which someone can adjudicate correct and incorrect interpretations. This “meaning” funds the argumentative commonplace that “words have meanings.’”[1] This sense of “meaning” dominates, implicitly or explicitly, the field of biblical studies; through most of the discipline, the premises that meaning subsides in texts, and that the legitimacy of an interpretation depends on the accuracy with which it identifies this subsistent meaning, provide the grounds for interpretive discourse. Nonetheless, it is precisely the intuition that words have “meaning” as an identifiable subsistent property that constitutes the single greatest impediment to a clear understanding of hermeneutics, and to discernment in interpretation. Indeed, the proposal that words do not “have” meaning as a subsistent property typically elicits the immediate challenge that without some such property, words and language must be meaning-less and all efforts at communication amount to nothing more than an anarchic cacophony of chaotic babble.

We have, however, an alternative mode of hermeneutical deliberation, one we deploy continually, a seamless reliance on a faculty so fundamental to everyday experience that only by patient teasing can we bring its fulness to critical attention. This alternative to the hermeneutics of subsistent meaning takes the inferential practices by which we navigate everyday life as an interplay of expression and apprehension. “Expression,’” in this context, refers to any sort of making-manifest, but particularly to the active offering of one’s ideas, feelings, fleeting thoughts, and so on (whether in language or gesture, drawing, vocalising, or other medium). “Apprehension” refers to the corresponding uptake of what is manifest: inference from observed expression. By learning about “meaning” from the more pervasive phenomenon of expression and apprehension, and from there toward reasoning about language as a special case — rather than beginning from language (which harbours subsistent “meaning”) and treating other patterns of apprehension as “the language of music,’” “the language of flowers,’” and so on — we can articulate a hermeneutic that adequately explains interpretive difference, and provides ways of evaluating interpretive claims outwith the customary bounds of exegetical correctness. A model for hermeneutics based on they interpretive practices by which we interact with the “blooming, buzzing confusion”[2] with which our senses provide us better suits our navigation of a world of interpretive difference than does the conventional hermeneutics’ focus on arriving at a correct interpretation. In the pages to follow, I will outline an abductive argument for the conclusion that we best understand hermeneutics when we begin from the general phenomenon of inference from observation.[3]

The proclivity to treat all manner of interpretive activity under the banner of “language” (with its invisible sidekick, subsistent “meaning”) has a history too long to rehearse here. The appeal of that intuition gains strength from its convergence with the near-universal desire to control interpretation, to suppress error and enforce the right.[4] The predominant discourses of biblical hermeneutics not only marginalise non-verbal aspects of communication, but indeed cultivate a sort of mystified tunnel vision that ascribes unique power and metaphysical status to verbal combinations of alphabetical (or logogrammatic) glyphs. The proliferation of such non-verbal modes of communication as images, video, and audio clips in digital media, however, as it pushes back at the long-standing hegemony of the printed page, alerts us to the urgent importance of a hermeneutic that takes account of non-verbal as well as verbal communication. Indeed, the role of non-verbal media in recent online political propaganda[5] forcibly opens the possibility that verbal expression operates not only as an atypical, but perhaps even subordinate mode of political rhetoric. Certain aspects of print-determined verbal hermeneutics remain usefully illuminating in the aftermath of our conducting a thorough housecleaning. Especially as the digital avalanche overtakes and bears us forcefully onward willy-nilly, though, we stand to benefit much more (and in the end to learn more about sound biblical interpretation) if we relax our disciplinary death-grip on the mode of reading that print culture has elevated to a nonpareil semiotic norm.[6] Instead, we can adopt an understanding of interpretation that draws on all our senses and accounts for broader phenomena of interpretation and meaning expressed in action, in tone, perhaps even in flavour, scent and texture. For instance, one can cavil indefinitely about interpretations of Mary’s attitude to Gabriel’s surprising news, but many will find particular depictions of the Annunciation much more persuasive than any grammatical or historical explication of Luke 1:26-38. After understanding the operations and effects of non-verbal modes of expression better, we then can recognise as extending to account for verbal meaning as well — a sensuous hermeneutic.[7]

The full case for a sensuous hermeneutic requires a more extensive treatment than this manifesto can offer, so here I will restrict myself to proposing a way of thinking about “meaning” that remains with the domain of visual interpretation while forgoing the habit of ascribing paradigmatic significance to words: As a first step, I propose a visual-communicative continuum that runs between alphabet and image.[8] In our daily round of expression, that continuum begins with plain old ordinary pictures and extends through varying degrees of stylisation until particular graphical forms attain the status of alphabetical glyphs — and we can communicate in diverging ways with diverging effects as we adopt graphical styles from various particular points on this continuum.[9] The discipline of biblical studies has been slow to recognise the extent to which the matters that the biblical authors treated in discursive alphabetical prose could otherwise have been expressed by other communicative gestures.[10] Film studies has established a stronghold in the biblical disciplines,[11] and iconographic studies have begun to take root (Christopher Rowland,[12] Yvonne Sherwood,[13] Heidi Hornik and Mikeal Parsons,[14] Cheryl Exum,[15] the subfield of graphic novelisation and comics theory,[16] and the work of the Centre for Reception History of the Bible at Oxford University under the leadership of Christine Joynes[17]). But these have not deflected the overwhelming momentum of the verbal-interpretive juggernaut. Often, even these studies perpetuate an underlying verbal priority even as they examine still and moving images; the object of study has changed, but some of the premises concerning “meaning” linger. In this essay, however, I propose to begin with the inevitably graphical dimension of linguistic (even “alphabetic”) interpretation, and proceed from there to the use of pictorial representation to interrogate and, if possible, undermine the disciplinary coherence of verbal hermeneutics in favour of a hermeneutic that acknowledges the various differing modes of communicative expression on equal terms. As we pursue the project of a more richly sensuous hermeneutics, such interrogations will constitute a fulcrum for amplifying the breadth of our sensitivity to increasingly complex communicative practices, and for essaying a first few faltering steps toward non-verbal means of articulating our theses.

The first step in my argument, then, entails a quick tour through the rough-and-ready graphical-communicative continuum. Let’s say that the pictorial end of the spectrum begins with images with no recognizably glyphic elements, something like a “pure” image (Figure 1[1] ).

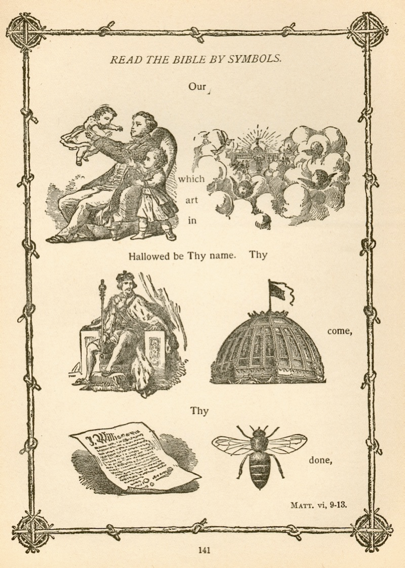

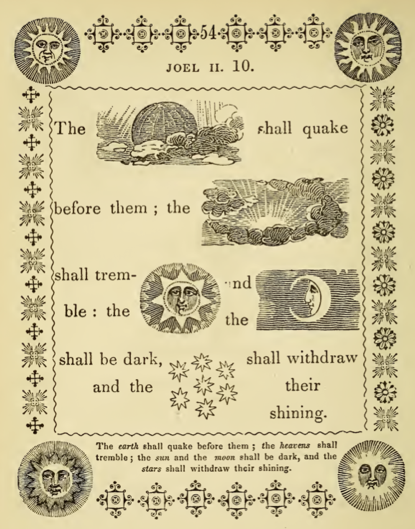

Moving from such a hypothetically ‘pure’ image toward verbal communication, we may enlist captioned art (in which a verbal appendix adjacent to or superimposed on the image constitutes a complementary but distinct element of an integrated whole) (Figure 2); and thence to pictured-words[18] (in which an image relies for its cogency on a viewer’s recognition of verbal signs intrinsic to the image within which they play a part) (Figure 3).

Next, importantly, come comics, in which image and verbal communication deliberately join forces – as they do also, differently, in such artifices as poetry plastique[19] and calligram (Figure 4).

Perhaps at the centre of the spectrum, logotypes and other such conventional paraglyphic signs stand where a siglum does the visual work of a name (Figure 5) — and the European-traditional form of the logo, the coat of arms (on which the use of letters is strictly deprecated).

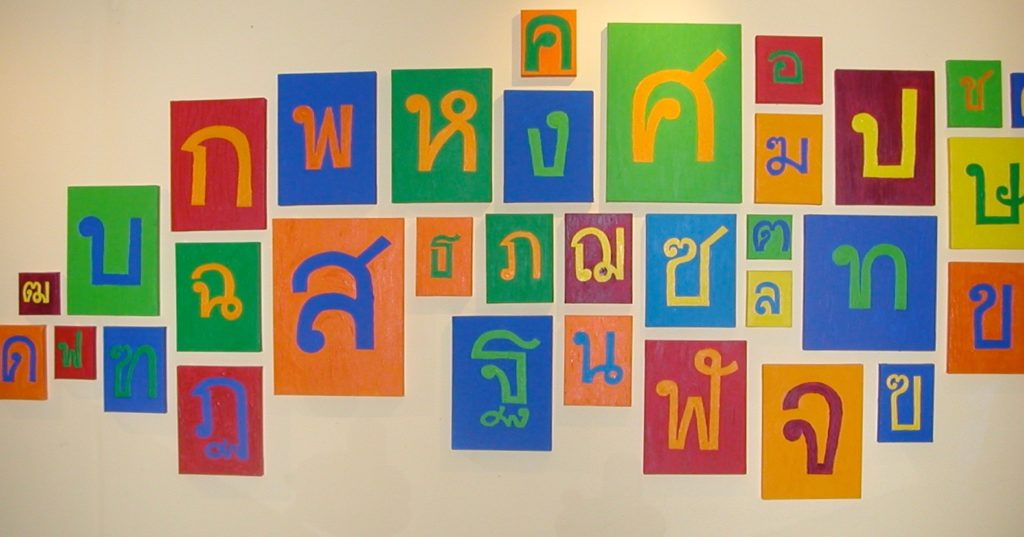

Thence we may proceed to illustrated verbal texts, a sort of opposite of comics in which word and images take varying proportions, the images serving to illustrate the more primary words; then rebuses, where pictorial signs substitute for words whether representationally or phonetically (Figure 6), picture alphabets[20] and alphabetic characters displayed for form rather than verbal coherence (Figure 7) [Photo of letters[2] from Happy Noodle in Evanston], and finally “plain” verbal texts such as the pages from which you are reading.[21] In each of these cases, the mode of expression involves more — and other — than simply the words that may be incorporated in the image.

✹

This continuum calls forth several observations. First, at any given point on the continuum, the verbal and imagistic forms of communication always inevitably interpenetrate one another; there is neither purely pictorial nor purely linguistic communication. The Mona Lisa incorporates no glyphic design elements or captions, and its “title” is a matter of ambiguous convention; still, the image properly known as La Gioconda does not escape the miasma of verbal communication which surrounds and illuminates and occludes the painting. If one thinks of the title as Mona Lisa, an abbreviated form of Madonna Lisa, does one then spell its title with two “n”s to avoid the vulgar connotations of the Italian slang “mona”? If one refers to the painting as La Gioconda, how does one deal with the resonances that join the model’s married name (Giocondo) to the sense of the Italian word “gioconda,’” the feminine form of an adjective for “amused, cheerful”? And at the opposite end of the spectrum, the ways that the glyphs of a verbal text look – their typeface or lettering style – inevitably inflect the ways that readers make sense of that verbal text. (It is no surprise that academic journals are set in stolid, readable, uninteresting serif[3] type rather than the whimsical, irregular hand-drawn lettering more common on cafe menus, posters, and signs for children’s lemonade stands.) Images cannot by dint of interpretive determination be isolated from linguistic influences, nor can glyphic text escape visual connotations. Their words alone are not the only source of their signification.

The mutual saturation of the glyphic with the image calls to mind a distinction proposed by Julia Kristeva and, slightly differently, Roland Barthes: the distinction between the genotext and the phenotext. In the ensuing discussion, I will follow George Aichele[22] in associating these terms with their corresponding biological equivalents; that is, the genotext, as with a genotype, provides the structure of signifying elements that give rise to various actual interpretations, and the phenotext (as with phenotype) designates the various manifestations of the text as we encounter it. Kristeva’s discussion of this distinction runs the gamut from downright murky to utterly opaque[23]; she defines ‘genotext’ in terms of the phonematic, melodic, sequential, associative, non-linguistic aspects of an utterance.[24] She stipulates that “[w]e shall use the term phenotext to denote language that serves to communicate, which linguistics describes in terms of ‘competence’ and ‘performance’”[25] — language, that is, as it does its job in the world of appearances. “The phenotext is a structure (which can be generated, in generative grammar’s sense); it obeys rules of communication and presupposes a subject of enunciation and an addressee.”[26] For the purposes of this essay, we should note that Kristeva betrays a textual overdetermination of this distinction when in another account she stipulates the “phenotext” to be “the printed text”: “ce phéno-texte qu’est le texte imprimé.”[27] On Kristeva’s account, genotext is a non-linguistic process of an utterance’s emergence into articulation; phenotext pertains to the particular utterance itself; genotext is (as it were) the Platonic ideal of the utterance, and the phenotext is each occurrence of the utterance.

Barthes characterises the distinction differently in “The Grain of the Voice.”[28] Barthes acknowledges Kristeva’s usage, applying it to baritone singers Charles Panzéra and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau.

The pheno-song (if the transposition be allowed) covers all the phenomena, all the features which belong to the structure of the language being sung, the rules of the genre, the coded form of the melisma, the composer’s idiolect, the style of the interpretation: in short, everything in the performance which is in the service of communication, representation, expression, everything which it is customary to talk about, which forms the tissue of cultural values (the matter of acknowledged tastes, of fashions, of critical commentaries), which takes its bearing directly on the ideological alibis of a period (‘subjectivity,’ ‘expressivity,’ ‘dramaticism,’ ‘personality’ or the artist).[29]

On the other hand, “the geno-song” on Barthes’s account,

is the volume of the singing and speaking voice, the space where significations germinate ‘from within language and its very materiality’; it forms a signifying play having nothing to do with communication, representation (of feelings), expression; it is that apex (or that depth) of production where the melody really works at the language — not at what it says, but the voluptuousness of its sounds-signifiers, of its letters — where the melody explores how the language works and identifies with that work.[30]

Put more simply, Barthes identifies Fischer-Dieskau’s phenotextual performance with a sort of abstracted (‘sterile’) mechnical correctness, but Panzéra’s genotextual performance with material bodiliness, a perceptible “friction between the music and something else”;[31] Wole Soyinka suggests simply that “one has soul, the other does not.”[32]

My own use of these terms (not determined by Kristeva, Barthes, Aichele, or anybody else’s prior usage) might take them in yet another different, related, direction. The genotext treats textuality in a formal, pure, uninflected sense, as the degree zero of signification; it constitutes the condition for the possibility of interpretation, the “something-here” that warrants (provokes, engenders) interpretation. The phenotext, then, is the text as it appears, φαίνειν, available to interpretation even as it is always already interpreted.

One can see from the start a sort of usefulness to this distinction in the biblical-studies world by reflecting on the relation between technical-exegetical study of the Bible and the burgeoning field of reception history; such a division would find its explicit manifestation in the time-hallowed discourse that works to separate and reconnect meaning and application. One might then reckon that in a seminar on the Pauline Epistles, our colleagues aim at determining the genotext of Romans (its pure, formal, uninflected, “actual” meaning), for instance, and that in a seminar on the reception history of Romans we consider its phenotext (the manifold ways that Romans has been received and put into effect among the centuries of its interpreters). Frances Young and David Ford have done valuable work along the lines of understanding a text as a musical score, a script, or a screenplay which awaits performance;[33] in terms of their works, the score/script/screenplay provides the genotext, and the performance actualises the phenotext. Most recently, Brennan Breed has developed an adventuresome account of text and meaning, interrogating the premise that any single phase in the composition of a text qualifies to function as a uniquely authoritative “original”; any particular instance of a text will generate a plurality of readings, so that the task of the interpreter arises not from giving the correct account of the origin and real meaning of a text, but rather to show and analyse the various ways that various texts have engendered various interpretive possibilities.[34]

✹

My description of the communicative spectrum may already have alerted you to ways in which the heuristic distinction between genotext and phenotext collapses under pressure: every phenotext instantiates a version of its genotext, and every genotext one could imagine always involves some sort of particular representation. If every genotext is at least faintly inhabited by representation (one of Breed’s arguments in The Nomadic Text[35]), one might well doubt that there ever is any such a thing as a formal, uninflected, actual “meaning” of a text. Even those who adhere to the possibility of ideal meaning will probably recognise the problems with thinking someone has ever arrived at it; for them, the genotext (so understood) exists as an asymptotic ideal to be approximated ever more closely, albeit never attained. But such a vision assumes the consequent: that there is a pure, ideal genotext in the first place. If the ideal meaning is in principle unattainable, how would we know it is there at all? The assumption that there must be some genotext runs through the score/performance model, and (differently) through Kristeva’s and Barthes’s descriptions of phenotext and genotext. The more intensely one looks for a genotext, the more one discovers phenotextuality all around. The distinction can still be useful heuristically, as a rough way of distinguishing aspects of a text about which everyone in a given constituency agrees — in the way that technical exegetes agree (with reservations) about the text of the Bible — but the phenotext/genotext distinction serves best to remind us that il n’y a pas de genotexte, that any alleged pure form of a text is already saturated with phenotextual characteristics.

These considerations underscore the limitation of the genotext/phenotext distinction. Where, for instance, would one locate the genotext of Dali’s Christ of St John of the Cross, which draws on textual narrative, observation of a particular landscape, an imagined overhead perspective on a first-century execution, and much more? And if we can recognise that La Gioconda exemplifies phenotextuality through and through, must we not acknowledge the same about verbal expressions (which never come to us except via the inflections of pitch and vocal tone, or handwriting, type, colour, context, and so on)? A focus on genotextual aspects of the Bible that brackets phenotextual aspects by interpretive fiat can most readily — perhaps only — be justified on ideological grounds, ideology being particularly amenable to dominant classes who assign privilege to reified non-existent entities.

So although I’m proposing a communicative continuum, that continuum cannot simply function strictly on a linear or even planar or triaxial basis (one could devise any manner of third axes; stylised-vs-natural, or saturated-vs-desaturated). The examples of poetry plastique[36] and the use of glyphic images as decorative art,[37] as noted before, do not fit neatly onto a single image-text axis. By the same token, the sorts of cognitive linguistic studies that inform type design explore the confluence of word and design, light-heartedly reflected in the recurrent flurry of commentators who discuss the apocryphal ‘study at an English university’ that allegedly found that readers can successfully pick out words even when their constituent letters are jumbled.

Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at an Elingsh uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt [sic] tihng is taht frist and lsat ltteer is at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae we do not raed ervey lteter by it slef but the wrod as a wlohe.[38]

Readers supposedly recognised the words in a sentence by the appearance of their elements and context more than by the precise spelling of the word. Typographers refer to word-shape as a bouma, and argue over the extent to which they should design typefaces with a view toward the criterion of amplifying the contribution of letterforms to word intelligibility. In all visual communication, though, glyphic composition constitutes only one aspect of the communicative gesture; apprehending and expressing inevitably, necessarily partake in non-glyphic communication. An interpretive fixation on ‘words’ will minimise or ignore innumerable communicative indices (colour, pitch, size, volume, scent, visual context)as it stifles exactly the healthy use of imagination appropriate to any sound hermeneutics — but especially the imagination requisite for a sensuous hermeneutic released from its captivity to the printed page.[39]

Last, one can readily produce examples of each of these modes of graphical communication from the visual reception history of the Bible.[40] From mosaics[41] (Figure 8) and illustrative paintings of biblical figures and scenes (Figure 9) , through the blockbook Pauper’s Bibles[42] (Figure 10), illustrated Bibles (Figure 11), Picture Bibles[43] (Figure 12) , Hieroglyphic Bibles of various sorts[44] (Figures 13 and 14), illuminated manuscripts, the contemporary illuminated and hand-lettered St John’s Bible,[45] to the current vogue of biblical passages displayed on abstract or sentimental photographic backgrounds as projections to illustrate sermons or inspire readers of social media, to the conventional printed biblical texts on which virtually every exegete relies. The conventional discourses of biblical interpretation rely on a textual reductionism that occludes the visual effects that attend even the most austere presentation of the Bible: the typeface (or script), the page layout, any graphical illustrations, and so on. Although these aspects of the text affect interpretation as well as the text — the letters and words — that is abstracted from them, the discursive power of this textual reduction far surpasses its theoretical justification. There can be no text-in-the-abstract apart from specific instantiations of it, but the predominant discourses of biblical studies typically exclude these necessary specifics from consideration.[46]

✹

The importance of the multidimensional semiotic continuum described above lies not simply in reminding interpreters that design matters (though it does), nor in re-opening the hermeneutical conversation to interpreters who articulate their sense of the verbal text in non-verbal modes. Granted that we communicate in both image and word (or, perhaps better, in imagetext, as W. J. T. Mitchell suggests[47]), then to the extent that our hermeneutical deliberations confine themselves to verbal analyses, in typescript and print, of verbally-defined versions of the Bible, not only do those deliberations suffer from the arbitrary constraint of textual reduction, but they moreover reinforce the ideologically enforced priority of verbal communication.[48] In order to break down that artificial confinement, and in order better to explore the ramifications of the constraints that verbal communication imposes on hermeneutics, the discourse of hermeneutics needs deliberately to slough off its own captivity to the printed word.

In other words, if as Wittgenstein suggested, “A picture held us captive. And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably,”[49] then perhaps a more sensuous hermeneutic can begin shifting the exclusive locus of the discourse of biblical interpretation from words-about-words to rich-media[50] articulations of problems and prospects relative to approaching and expounding the Bible. The exemplary work of biblical exegetes comparing more or less representational depictions of biblical scenes to the ways the Bible narrates these scenarios will grow even stronger and richer as scholars grasp the theoretical continuity (and peculiarity) of technical exegesis with expressive and critical discourses in non-verbal media.

That path has already been opened, although the academic discipline of biblical hermeneutics tends to ignore that discursive path. The particular provocation for this essay’s efforts lay in an essay that René Magritte composed in 1929 for La Révolution Surréaliste, entitled “Les mots et les images.”[51] In eighteen line drawings[52] (with printed captions), Magritte interrogates the assumption that words and images can be distinguished as neatly as we customarily assume. Our customary approaches to words and images invoke two markedly different cognitive interpretive modes, even though (as Magritte points out), “[i]n a picture, the words are of the same material as the images.”[53] This short graphic essay makes explicit some of Magritte’s interest in subverting those interpretive assumptions, and prefigures several of his hermeneutical images.

The visual aphorisms in the essay involve the ways that language and image interweave and create the illusion that they are somehow tethered to realities that they purport to represent (“Some objects get along without a name” showing a generic dinghy floating on the sea; “An object [in an image] can make us think that there are other objects behind it,’” depicting a brick wall with hatching behind it that, conventionally, suggests a space cast into shade; “The words that serve to designate two different objects do not show what can differentiate the objects from one another,’” depicting an indistinct blob on which the two phrases “character losing their memory” and “woman’s body” are handwritten). Two of the image-aphorisms provide far-reaching challenges to the logocentric tunnel vision of textual hermeneutics: one reminds readers that, as I noted before, “in a painting, the words are of the same material as the images,’” and the second that “[a][5] n image can take the place of a word in a proposition,’” a reflection that resonates with the Hieroglyphick Bible cited above. With both these premises, Magritte tugs at the loose thread that binds mystified semiotic properties to alphabetical graphical marks. Written words are nothing more than ink on paper – as sketches and portraits and landscapes are paint on canvas. Although we deploy markedly different strategies in our interpretations of verbal and pictorial markings, the markings themselves don’t differ in intrinsic properties. A narrowly verbal hermeneutic tends (for example) to occlude the extent to which all interpretation inevitably depends on imagination as well as syntax and semantics; a hermeneutics that takes account of the graphical saturation of written verbal communication opens the door that leads out from the sterile and straitened debates over objectivity, meaning, and intention that beset the familiar discourses relative to biblical interpretation.

Magritte’s most famous experiment in combining word and image occurs not in “Les mots et les images,’” however, but in a painting executed at approximately the same time. La trahison des images depicts a smoking pipe against a flat background, suspended over the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.’” The canvas picks up and amplifies several of Magritte’s messages from “Les mots et les images”: “One sees the images and the words in a painting differently” — “An object never performs the same function as its name or image” — and especially Magritte’s contrast between real and represented objects.[54] The words on the canvas are true enough; the words themselves are not a pipe, the demonstrative pronoun “ceci” is not a pipe, the painting is not a pipe, and so on – but the image persistently and clearly depicts that which the caption denies. One may explore the ramifications of the painting at length (as did Michel Foucault[55]), but at the very least the painting calls into question the transparency and autonomy of written words; never has the context-dependence of language stood out more vividly.

Although this image now ranks among Magritte’s best-known works, and evidently made a small sensation when first exhibited, it was not shown or reproduced for 20 years after its first appearances.[56] (He subsequently returned to the image a number of times — Martin Lefebvre counts no fewer than ten iterations of this specific image, not counting sketches and letters[57] — eventually in 1966 heightening the hermeneutical stakes in Les Deux Mystères by representing a version of the original image, framed, in front of another massive, floating pipe).

The material of the words and images may be the same in La Trahison des Images, but one would think it quite odd if an art critic treated the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” simply as a matter of colour and curves, of script rather than roman letters. The script signifies not simply as a design element, but also (decisively?) as the words it transcribes. Although the typography/chirography/painting of the words makes a difference, as do the colours and the positions of the words on the canvas, Magritte invites his viewers to consider the semiotics of representation, of textual hermeneutics, of the relation of words to images when they’re incorporated together in a single art work, and of the repetition of one thematic motif in similar but not identical versions – just for starters. If on Magritte’s canvas the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” do not mean, simply, “this is not a pipe,” how are our textual hermeneutics to take account of the non-verbal communication that decisively inflects the interpretation of this relatively straightforward phrase? With this painted image, Magritte provokes hermeneutical reflection without dictating the terms on which the interaction will conclude; there’s no “therefore” or “obviously” to these paintings (a point which Magritte himself endeavours to make in numerous interviews and essays).[58] To a certain extent, Magritte’s Trahison reverses the textual reduction that characterises biblical scholarship by making it impossible to consider the words of his images apart from the images themselves; but if one can’t satisfactorily make sense of the lettering on Magritte’s canvas without considering its context, one might make the same claim against textual reduction in biblical criticism.

Magritte represents an early twentieth-century challenge to conventional assumptions about interpretation, displaying the mutual saturation and mutual interrogation of words and images; his hermeneutical successor Mark Tansey advances the critique of interpretive reason in a comparable but divergent front, using images metacritically to display the problematic coherence of the practice of critical interpretation.[59] In an image from an early phase of his hermeneutical reflection, in the paired images entitled Modern/Postmodern, Tansey proposes a distinction between a modern perspective on interpretation – in which the interpreted framed image has depth behind the canvas and reaches out to act upon, indeed to kick the viewer in the teeth – from a postmodern perspective on interpretation, in which the initiative for interpretation falls to the viewer, who imposes interpretation upon a passive (and, typically, closed) text, trying to kick his way into the canvas. Tansey’s series of hermeneutical images from the early nineties invokes familiar texts and figures from poststructuralist theory in pictorial meditations on the nature, effect, and clarity of communication. Figures strain to scale pages shown as rock walls (in a canvas entitled Close Reading), peer intently into a murky textual obscurity (View From Mt. Hermeneut), immerse themselves into the opaque textuality of a cave (in Reader), wrestle at the edge of a textual abîme (in Derrida Queries de Man), endeavour to escape their textuality by shedding the clothing of words (in John the Baptist Discarding His Clothes in the Wilderness), and excavate the Grand Canyon (Constructing the Grand Canyon, with cameo appearances, again, by Derrida, De Man, and Foucault, and with a Yale banner behind them). In these images, Tansey suggests visually that interpretation of verbal textuality entails risky labour in precarious circumstances; that verbal textuality is obscure, that textuality covers and conceals; that textuality is both natural and given (on one hand), and constructed (on the other). While Tansey uses mostly indistinct words and pages as design elements, he specifically makes the text illegible (apart from occasional appearances of title lines); his point in incorporating these words is to comment on textuality, not on the particular words of Derrida and de Man. Biblical interpreters may recognise their particular implication in the biblical resonance of such canvases such as Doubting Thomas, The Myth of Depth (in which Jackson Pollock walks on water, as other New York School artists and critics look on), Sola Scriptura, and The Key (in which a man and woman stand outside a locked garden, whose gate is surmounted by a sword-wielding angel on one pillar and a snake wound around a tree on the other). With vivid images, Tansey invokes a hermeneutics of opacity, of risk, of exploration, of conflict, and of uncertainty. Indeed, such characterisations fall very far short of the full hermeneutical force of the paintings; by presuming to supplement the images with words-about-them, I manifestly attenuate that which Tansey communicates with the images. Still, as W. J. T. Mitchell says of a sketch he provides in Iconology, “I present this model graphically, not to argue for its rightness, but to make visible the way we divide up our universe in common parlance.’”[60] Or as I would say, “not because I want to prove that it is right, but to show that it is possible” — and to show on that basis another, more compelling way of framing our interpretive problems.

At this point, some may object that this approach to interpretation leads to the nihilism of universal meaninglessness. Quite the contrary: I contend that our patterns of expression and apprehension are quite thoroughly constrained[61] — though not by alleged intrinsic or subsistent “meanings.’” Our communications function predictably and (on the whole) quite successfully because they rely on our predictable participation in effective patterns of shared behaviour and custom. The more thoroughly one complies with one’s neighbours’ communicative expectations, the more likely one’s communication with these neighbours will play out to mutual satisfaction.[62] These shared patterns of communication include predictable (non-arbitrary) patterns of intonation, personal appearance and attire, adoption or avoidance of nonstandard usage (slang, pidgin, jargon), gestures, and shared indications of taste (the music to which one listens, the literary sources to which one alludes, the football team one supports). A complex of behaviour, expression, taste, and attitude constitutes a signifying practice,[63] a constellation of ideas and actions that decisively and effectively govern utterances and interpretations in particular circumstances. The range of behaviour and expression that a common observer might associate with a particular social niche thus exemplifies such a signifying practice, as when someone adopts the Received Pronunciation (and diction), wears neat clothing in muted colours, favours the opera over dance clubs and cricket over football (or supports no sport at all), evinces dismay at breaches of formal etiquette, drops the names of titled persons with painstakingly correct styles of address, all in order to underscore an identity as “posh.’” The sort of conventionalised patterns of expression and recognition that operate on a community-sized scale in the signifying practices of social classes, pockets of cultural resistance and acquiescence, professions and other street gangs, operate as well on the vast scale of linguistic (and to some extent gestural, culinary, and aural) cultures. Language plays a role in the ordering of these groups, and a single person can only rarely defy even a handful of the conventions of language without losing intelligibility; but language in itself does not have meaning as an attribute distinct from the semiotic practices of its users (any more than printed notes of currency have value apart from the economic conventions that treat them as tender, or a red light has the intrinsic meaning of “stop” apart from conventions of traffic management).[64]

Thus this presentation proposes approaching hermeneutical deliberation from the starting-point of more general interpretive behaviour (estimating the hour of day by the intensity and angle of sunlight, reckoning apparent distance and trajectory by the size and motion of a known object, and so on), and considering linguistic interpretation as an outlying instance of unusually precise expression and inference. Rather than thinking of all communicative behaviour on the model of language, we should consider language on the model of non-verbal modes of expression. This has the salutary effect of clarifying that interpretive discourses legitimately propose their expositions not solely or paradigmatically in technical academic exegesis, but in any expressive mode whatever. A baker may just as well devise interpretive croissants as a Pauline scholar writes a technical article. The legitimacy and soundness of interpretations derive from the discourses to which they affiliate, not by the nature of language or textuality.

This model of interpretation does not provide access to a degree-zero realm of pre-interpretive “meanings,’” control of which might enable us to require others to accede to our interpretive conclusions. The fantasy of interpretive control so cherished by the official (White, male, bourgeois, Euro-American) biblical academy distracts practitioners from the more pertinent, more attainable goals of presenting cogent arguments with specific evidence, warrants, and rationales. Repeated insistence that we are the experts, we adjudicate legitimate interpretation avail naught in discursive arenas that don’t already accord biblical academics that status; attending to the need to communicate persuasively would do more for the public authority of the discipline than do convoluted accounts of intention, objectivity, alleged origins, and so on.

What difference does this make?[65] It need not make any difference whatever; indeed, Stanley Fish makes the argument that theory cannot make a difference in the “Consequences” section of Doing What Comes Naturally.[66] The point of the exoteric sensuous hermeneutics I expound here, however, lies in their capacity to provoke and illuminate, not their capacity to sustain the illusion of control. The goal of hermeneutics, on this account, is to know more and to integrate what is known more fully with the range of interpretive claims. Thus, a conventional historical critic might continue to go about her work in almost exactly the same way she has for decades, with the proviso that this is simply how conventional biblical criticism works (rather than with the justification that this accords with the very nature of interpretation itself). I have observed that almost all conventional scholars go ahead so to do. Exoteric hermeneutics do not supply scholars or civil or ecclesiastical authorities with a stick to beat recalcitrant erroneous interpreters.

On the other hand, this approach does help explain the relations among various interpretive emphases and interests. It does undermine flat claims to “correctness,’” “naturalness,’” or “common sense.’” Thinking about hermeneutics sensuously does provide a theoretical frame for articulating the relation of linguistic hermeneutics to such related practices as interpretation in non-verbal modes of expression, translation from one language to another, and the many relations between the vocation of biblical interpretation and other lived identities. The entire cottage industry of “theological interpretation” retreats from its prominence as a burgeoning subfield with a peculiar problem at its basis and a tortured relation to technical exegesis as its trademark, and takes on the mantle (or perhaps the cassock) of interpretation of biblical texts in the contexts of doctrinal, homiletical, ecclesiastical claims made about them. Even conventional biblical critics nowadays will make at least a perfunctory acknowledgement that their work is not “objective”; the pivotal importance of sensuous hermeneutics lies in demonstrating the stark provinciality of hermeneutical claims to universality and authority. Sensuous hermeneutics actively bring to the fore, with robust theoretical backing, the vivid alternatives possible when one suspends the privilege of textual reduction and abstraction. The explosion of interest in reception history testifies to what often remains an under-theorised eagerness to engage biblical texts more imaginatively than the discipline has condoned. These alternatives need not inhabit a marginal existence dependent on the assumption that technical exegesis gets at the real meanings that legitimate, or delegitimate, visual representations; sensuous interpretive practice actively promotes the role of imagination in apprehending plausible interpretations on grounds less technical and often more compelling than the desiccated abstractions in which conventional disciplines trade.

The greatest difference thus involves cutting interpretive discourses off from overblown pretensions to intrinsic authority. Mystified subsistent meanings no longer warrant the coercive power of our claims; only persuasion in the full rhetorical sense wins the approbation of viewers and readers. One reader may lend greater credence to an author who seems insouciantly impious, whereas another trusts authors whose names are followed by the initials of a religious order, and another may discount the scholarship of attractive women academics on the prejudice that genuine scholars are homely, or may ignore non-European scholars on the grounds of their postcolonial partisanship, and so on.

This essay has dwelt first on the visual relationship of words and images, and second on the ways that we might grow out of the constraints that limit our imagination of how the Bible comes to expression in the visual arts[67] by taking a cue from Magritte and Tansey, who deployed the hallmark “realism” of painterly representation to point beyond the artificial limitations of painted discourse. But this only begins the work of a sensuous hermeneutic. As interpreters become more sophisticated in thinking through biblical interpretation as a family of signifying practices, we will learn the conventions and idioms indigenous to each such practice, and will learn how various criteria flex and give, or remain rigid — rather than deferring in each case to the disciplinary imperatives of academic biblical scholarship (admirable though it be). We will be better able to parse the signifying practices appropriate to ecclesiastical appropriation of Scripture from the practices required for technical interpretation in the secular academy. No one signifying practice controls a uniquely privileged methodological or ethical key to interpretive legitimacy; within each interpretive signifying practice, indigenous conventions will raise up some interpretations as sounder and more compelling, and will discountenance others as uninteresting, poorly-executed, unsound. In order to have made sense of everything we have experienced in all our lives, we must have had viable conventions and criteria by which we venture and assess interpretations (of sunlight, of weather, of the speed of an approaching bicycle when you’re crossing the Turl Street). The same capacities will serve us well as we undertake interpretations of the Bible; though we may falter at first, and err more often than we’d like, we will in short order be able to acclimate ourselves to interpretations authorised on the strength of characteristics that do not depend primarily on their deference to an unreachable subsistent meaning. But in that light, what we now call ‘reception history’ will be readily intelligible simply as “biblical interpretation under circumstances other than those that prevail right here, right now.”[68] When we reach that day, the quest for an authoritative “correct” meaning will seem at first less urgent, and eventually irrelevant. We manage quite well with art, music, drama, cooking, perfumery, and caresses of different sorts for different audiences, and just as we evaluate instances of these as more or less satisfactory vary depending on culture, interests, experience, and even religion. In the same way, we can manage very well by treating biblical interpretation imaginatively, seriously, variably, sensuously.

[1] In January 2016, Jerry Seinfeld attracted attention on the internet for a short monologue on the premise that “words have meanings,” that it is improper to refer to the American globular breakfast pastry as a “donut hole” because holes, by definition, are an absence of substance. His monologue can be viewed at <http://digg.com/video/seinfeld-standup-colbert> (viewed 11 July 2019).

[2] William James, The Principles of Psychology (New York: Henry Holt, 1890), 488.

[3] Because this argument points away from language and toward other modes of expression and apprehension, a written essay provides the least propitious medium in which to articulate this thesis. Indeed, it has earlier been presented as a slide lecture, and would probably make an even stronger case as, perhaps, a video recording — or a guided walking talk, wherein one might directly invoke smells and flavours. Nonetheless, even a straightforward prose essay, however, should be able to make an initial case for the plausibility of this model of expression and apprehension.

[4] Think, for instance, of the complexion of on-going arguments about the Bible and ethics: If it were generally agreed that there were no subsistent meaning which warranted requiring others to do this or not do that, such debates could more gracefully modulate to discussions of varying ways one might most satisfactorily embody an ethos congruent with the ways one may apprehend God’s approbation and disapprobation expressed in the Bible. As the most prominent conventions of interpretive discourse involve the premise that a latent ‘meaning’ subsists as a property of biblical strictures on behaviour, though, advocates of various positions on the Bible and ethics persistently argue over what this or that text really means (despite the long history of conscientious interpreters arriving at divergent conclusions).

[5] The advertising industry has, of course, subordinated linguistic claims about particular products to implicit visual claims that a given brand’s automobile, or hairspray, or undergarments, or coffee will render the user irresistibly attractive, happy, and healthy.

[6] My invocation of semiotics here provides a convenient point at which to acknowledge Mieke Bal’s powerful intervention in biblical studies in the late ’80s, in her appearances at conferences and in her publications, of which Lethal Love: Feminist Literary Readings of Biblical Love Stories (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Pres, 1987), Murder and Difference: Gender, Genre and Scholarship on Sisera’s Death, trans. Matthew Gumpert (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1988), Death and Dissymmetry: The Politics of Coherence in the Book of Judges (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988) and especially important for the topic of this essay, Reading “Rembrandt”: Beyond the Word–Image Opposition (Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991) — and her Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative, trans. Christine van Boheemen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985) and On Story-Telling: Essays in Narratology (Sonoma, CA: Polebridge Press, 1991) provided an early influence on the direction of this essay.

[7] A sensuous hermeneutic, on this account, differs from the discourses surrounding “orality” and “secondary orality” inasmuch as a fully sensuous hermeneutic interrogates any essentialised or oversimplified account of sundry media, especially those which emphasise one particular faculty of sensing at the cost of neglecting the interpretive contributions of others. Communicative expressions come in all manner of media: sounds, sights, scents, flavours, touches, and more, and none is satisfactorily reduced to the others (as I will argue later).

[8] Scott McCloud proposes a triaxial version of the continuum I propose here (in Understanding Comics, 52-3), with vertices at “the picture plane,” “reality” (in inverted commas), and “meaning.” Reality and the picture plane are connected by “the retinal edge”; meaning and the picture plane are connected by the “conceptual edge,” with a “language border” distinguishing glyphic and non-glyphic modes of expression. McCloud’s version emphasises pictorial representation (for obvious reasons), but looks toward glyphs to cite the company logotype (#76 – apparently missing in the edition of Understanding Comics in hand), the title logo (#77, “the word as object”), and the spelled-out sound effect (#78, “the word as sound”).

[9] My initial explorations of specifically graphical dimension of this topic have been deeply informed by McCloud’s Understanding Comics; Edward Tufte, Envisioning Information (Cheshire, Conn.: Graphics Press, 1990), Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative, (Cheshire, Conn.: Graphics Press, 1997), Beautiful Evidence (Cheshire CT: Graphics Press, 2006); W. J. T. Mitchell, Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986); Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994); Jeff Ward, “Towards a Rhetoric of Word and Image” (MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2001); and René Magritte, “Les mots and les images,” La Révolution Surréaliste 12 (December 1929), among many others.

[10] Here Tom Boomershine stands out as an obvious counterexample. A generous conversation with him in — what? Chicago, 1988? — proved more generative a provocation to my thinking than either of us could have guessed at the time. Since that meeting, over the last three decades, interpreters have devoted increasing attention to cinematic and graphic representations of biblical themes, although such work still constitutes a mere trickle in the torrent of biblical interpretation.

[11] Adele Reinhartz, Scripture on the Silver Screen (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2003); Reinhartz, Jesus of Hollywood, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007); George Aichele and Richard Walsh, eds., Screening Scripture: Intertextual Connections Between Scripture and Film (Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 2002); Walsh, Reading the Gospels in the Dark: Portrayals of Jesus in Film (London and New York: Trinity Press International; 2003); Walsh, Finding St Paul in Film (Edinburgh, T&T Clark, 2006); Aichele and Walsh, “Metamorphosis, Transfiguration, and the Body,” Biblical Interpretation 19 (2011), 253-275; W. Barnes Tatum, Jesus at the Movies: A Guide to the First Hundred Years and Beyond (3rd ed., Salem: Polebridge, 2013); Joan E. Taylor, ed., Jesus and Brian: Exploring the Historical Jesus and his Times via Monty Python’s Life of Brian(London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015); Rhonda Burnette-Bletsch, The Bible in Motion: A Handbook of the Bible and Its Reception in Film, Handbooks of the Bible and Its Reception 2, 2 vols. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016); Aichele, Peter D. Miscall, and Walsh, “Heirs Apparent in Juxtaposition: David in Samuel-Kings and Michael Corleone in The Godfather,” Biblical Interpretation 26 (2018), 316-333; Walsh, ed., T&T Clark Companion to the Bible and Film, Bloomsbury Companions (London: T&T Clark, 2018).

[12] Christopher Rowland, Blake and the Bible, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011).

[13] Yvonne Sherwood, A Biblical Text and its Afterlives: The Survival of Jonah in Western Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

[14] Heidi J. Hornik and Mikeal C. Parsons, Illuminating Luke, 3 vols (Harrisburg, Pa.: Trinity Press International, 2003); (eds.) Interpreting Christian Art, (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2008); The Acts of the Apostles through the Centuries, Wiley-Blackwell Bible Commentaries (Malden, MA and Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2016).

[15] J. Cheryl Exum, Plotted, Shot, and Painted: Cultural Representations of Biblical Women (Sheffield : Sheffield Academic Press, 1996); Between the Text and the Canvas : the Bible and Art in Dialogue (Sheffield : Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2007); Art as Biblical Commentary: Visual Criticism from Hagar the Wife of Abraham to Mary the Mother of Jesus (London: T&T Clark, 2019).

[16] Cf. Scott S. Elliott, “Comic Testaments, Graphic Novels, and the Biblical Imagination,” Translation and the Machine: Technology, Meaning, Praxis. Steve Berneking and Scott S. Elliott, eds. (Rome, Italy: Edizioni di Storia e Letturatura, 2008) 103-124; “Jesus in the Gutter: Comics and Graphic Novels Reimagining the Gospels,” Postscripts: The Journal of Sacred Texts and Contemporary Worlds 7, no. 2 (2011): 123–148; “Transrendering Biblical Bodies: Reading Sex in The Action Bible and Genesis Illustrated” in Comics and Sacred Texts : Reimagining Religion and Graphic Narratives (Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2018), 132-148; Dan W. Clanton, Jr., ed. The End Will Be Graphic: Apocalyptic in Comic Books and Graphic Novels (Sheffield, U.K.: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2012); Zanne Domoney-Lyttle, “Drawing (non)Tradition: Exposition and Interpretation of Matriarchal Narratives in ‘The Book of Genesis, Illustrated by R. Crumb’,” (PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 2018).

[17] Christine Joynes, “Visualizing Salome’s Dance of Death: The Contribution of Art to Biblical Exegesis,” in Between the Text and the Canvas, eds. J. Cheryl Exum & Ela Nutu (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2007), 145-163; Perspectives on the Passion: Encountering the Bible through the Arts, ed. Christine Joynes (London: Continuum, 2008); “A Place for Pushy Mothers? Visualizations of Christ Blessing the Children,” Biblical Reception 2 (2013), 117-133; “Re-visioning Women in Mark’s Gospel through Art,” Biblical Reception 5 (2018) 83-97.

[18] John Vachon, Boy from out of Town Sleeping in the Railroad Station Radford, Virginia, December 1940; my thanks to Jeff Ward for calling this image to my attention.

[19] Charles Bernstein’s term for the convergence of non-verbal graphic art with verbal poetry: “Not words and pictures but poems as visual objects (read: subjects). Not poems about pictures but pictures that are poems. Not words affixed to a blank page but letters in time.” Poetry Plastique (New York: Granary Books, 2001), 7.

[20] Consider, for example, such instances as Brandon Voorman’s Everyday Alphabet, <http://brandonvrooman.deviantart.com/art/Everyday-Alphabet-159925054> or Yousuke Ozawa’s Satellite Font <http://satellitefonts.tumblr.com> (former versions of this essay pointed to Dean Allen’s page <http://www.textism.com/photos/?s=14>, the Alphabet Project at <http://www.fotolog.net/alphabet/>, and this sculptural alphabet <http://www.jellyassociates.com/happy_10.html>, all of which sites are now inactive). Active sites viewed 11 July 2019.

[21] Note that even “plain printed text” differs from page design to page design. A single-spaced A4 page of 12-point Times New Roman is not the same as a page from one of William Morris’s Kelmscott Press editions. The biblical guild reacted with atypically consensual distaste for the type design chosen for the American Bible Society’s third edition of their Greek New Testament.

[22] In The Control of Biblical Meaning (Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 2001), 15-17. I should confess here that this reverses the categories of phenotext and genotext as I have apprehended them before — part of the reason I here set out a fuller exposition of the terms.

[23] Johanne Prud’homme and Lyne Légaré provide helpful clarification in their 2006 online essay, “Semanalysis. Engendering the Formula,” in Louis Hébert (dir.), Signo, Rimouski (Quebec), <http://www.signosemio.com/kristeva/semanalysis.asp>.

[24] Revolution in Poetic Language, trans. Margaret Waller (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), 86.

[25] Revolution, 87.

[26] Revolution, 87.

[27] Σημειωτικὴ: Recherches pour une sémanalyse (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1969), 219.

[28] Image-Music-Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill & Wang, 1978), 179-189.

[29] Image-Music-Text, 182.

[30] Image-Music-Text, 182.

[31] Image-Music-Text, 185.

[32] “The Critic and Society: Barthes, Leftocracy, and Other Mythologies,” Black American Literature Forum, 15 (1981), 140; as cited in Jonathan Dunsby, “Roland Barthes and the Grain of Panzéra’s Voice,” Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 134:1, (2009), 115.

[33] Frances M. Young and David Ford, Meaning and Truth in 2 Corinthians (London: Wm. B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1987); Young, The Art of Performance: Towards a Theology of Holy Scripture (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1990); and much of the work emerging from the Scriptural Reasoning project <http://www.scripturalreasoning.org>, accessed 9 August 2016. Earlier, Nicholas Lash made a powerful intervention in this field with the essays that became Part II of Theology on the Way to Emmaus (London: SCM Press, 1986), 37-92: “Performing the Scriptures,” “What Authority Has Our Past?,” “How Do We Know Where We Are?” and “What Might Martyrdom Mean?”.

[34] Brennan Breed, Nomadic Text: a Theory of Biblical Reception History (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2014). Breed’s argument and diagnosis cohere closely with that proposed here; the principal grounds of difference arise from his primary concentration on the linguistic-textual dimensions of the text, as opposed to my own emphasis on foregrounding aspects of interpretation that emerge more powerfully when we avert our attention from the strictly linguistic dimensions of a text; and his willingness to grant an “immanent potentiality” to the text, which to my mind too closely resembles a stand-in for subsistent meaning.

[35] “[T]he oldest imaginable Hebrew text of the story of Job is simultaneously a reception as well as an original.” Breed, The Nomadic Text, 2.

[36] For instance, the Poetry Plastique exhibit at the Marianne Boesky Gallery, 535 W 22nd St, New York, NY (9 February – 10 March 2001) or Tom Phillips’s A Humument (1973)

[37] Franco Sanno, “Alphabet Art,” Galleria La Fenice, Sassari, Italy (20 September – 15 October 2002).

[38] ‘Rdiaeng,’ by Steve Dodson, <http://www.languagehat.com/archives/000840.php> (accessed 20 March, 2019). Among the follow-up points, many of which can be reached from LanguageHat’s page, one should acknowledge that this works less well with a higher proportion of long words, or in languages that use inflectional endings, with words including a high proportion of vowels, and words with a lower proportion of ascenders and descenders. See also the forum thread “Bouma as bounded map,” <http://typophile.com/node/15432> (viewed 11 July 2019).

[39] We ought also to bear in mind that this essay primarily concerns visual communication — while aural, gustatory-olfactory, tactile, and other communicative modes involve innumerably more possible dimensions of signification, as Proust’s madeleine testifies.

[40] Commendable as is the initiative and the theoretical work done in the interests of the American Bible Society’s “New Media Project” (<http://americamagazine.org/issue/279/article/internet-bible>, visited Nov. 1, 2014), the term “transmediation” seems too facile a term for the multifarious process in which a printed text is expanded into a cinematic representation.

[41] Such as those documented at the Eufrasiana Basilica at <http://nickerson.icomos.org/euf/> (accessed 21 March 2019).

[42] For one example, cf. <https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1040376f/f7.image> (accessed 21 March 2019).

[43] The New Bible Symbols: The Bible in Pictures, Max Bihn and James Bealings (Chicago: John A. Hertel Co., 1922), p. 149.

[44] The Hieroglyphic Bible (New York: James Miller, 1870); Picture Puzzles, or, How to Read the Bible by Symbols (Toronto: J. L. Nichols & Co., 1899).

[45] The hand-lettered and illuminated Saint John’s Bible, housed at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library of Saint John’s Abbey, Collegeville, Minnesota.

[46] Text criticism, of course, devotes significant attention both to the scripts in which manuscripts are composed and to any material clues to provenance and history. These considerations are permitted for establishing the text, but are then usually excluded from interpretations of the (now-abstracted) passage.

[47] Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994); Wiesenthal, Christine, and Brad Bucknell, “Essays into the Imagetext: An Interview with W. J. T. Mitchell,” Mosaic 33 (2000): 1–23.

[48] When I ascribe ideological character to the prioritisation of verbal communication, I do not mean to suggest that the world would be a better place if people prioritised pictorial or gestural communication. Rather, I intend simply to emphasise the extent to which the ascribed priority of verbal communication, and especially graphical verbal communication, outstrips the demonstrable importance of other modes of visual, aural, tactile, olfactory and even gustatory communication.

[49] Philosophical Investigations, §115. Trans. G. E. M. Anscombe. Third ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1968).

[50] Graphical, audio, video, and verbal information, along with adaptive instruction on how these come into play — with an open gateway to further as-yet unarticulated possibilities.

[51] La Révolution Surréaliste 12 (December 1929): 32–3; reprinted in Écrits Complets, ed. André Blavier (Paris: Flammarion, 1979), 60-61, and in the René Magritte Catalogue Raisonné, ed. David Sylvester; I: Oil Paintings 1916-1930, David Sylvester and Sarah Whitfield. The Menil Foundation. (London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 1992), 110. “Les mots et les images” can easily be viewed online with a simple web search, but it has not modulated into the public domain in most of the world, so I regretfully do not link to it here. The English translations from Magritte’s French are my own.

[52] One should not overlook the decision to render Magritte’s captions with print, rather than the handwritten versions he supplied in early versions of his manuscript. Cf. René Magritte Catalogue Raisonné, ed. Sarah Whitfield; VI: Newly Discovered Works: Oil Paintings, Gouaches, Drawings, David Sylvester and Sarah Whitfield. The Menil Foundation. (London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2012), 71-73; Michel Draguet, Magritte tout en papier (Paris: Hazan, 2006), 55-59.

[53] “Les Mots et les images,” 60.

[54] “Les Mots et les images,” 60-61.

[55] This is Not A Pipe. Trans. and ed. James Harkness. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983). The painting does a better, more vivid, much more concise job of communicating with its viewers than does any commentary, perhaps particularly this one.

[56] Sylvester, Magritte, 170.

[57] Martin Lefebvre, “‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe(rie)’: propos sur la sémiotique et l’art de Magritte,” in Images et sémiotique: sémiotique pragmatique et cognitive, Bernard Darras, ed. (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 2006), p. 46: “Il existe de nombreuses versions de cette œuvre qui jalonnent le carrière de Magritte comme l’un de ses thèmes préférés. En effet, en comptant les toiles, les gouaches, la version intitulée Les deux mystères, etc., on trouve non moins de dix versions de La trahison des images produites entre 1929 and 1966.”

[58] One might suspect that Magritte’s resolute refusal to admit any message or explanation of his works would tell against the premise of Silvano Levy’s Decoding Magritte (Bristol: Sansom & Co, 2015); Levy himself, however, tries to elude Magritte’s strictures against extracting an articulated coherent theme to his works.

[59] Tansey’s works are not in the public domain. Though they are frequently reproduced online, and one can often find them with a web search for their titles (perhaps with Tansey’s name) as well, they cannot be displayed here.

[60] Iconology, 16.

[61] “Multiple constraints — which are ultimately sociopolitical — stop the signifying process at one or another of the theses that it traverses”; Kristeva, Revolution, 88.

[62] Prof. Dana Moser of the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, identifies this general phenomenon as “context-sensitive semantic subtlety” in his 2016 Convocation Address (personal communication, 29 May 2016). People will exhibit this capacity to varying degrees, of course; some parochial or narcissistic minds will decline to consider any systems of signification other than those already familiar to them, and others will insist that the contexts that seem obvious to them are intrinsic and natural (“words have meanings!”), whereas still others (such as the students Prof. Moser had in view) will revel in the indefinite possibilities of signification afforded by different cultures, media, and languages.

[63] The term “signifying practice” operates in several discourses to describe a regime of practices that support and reinforce each other, toward the end of constituting a particular semiotic community; cf. Julia Kristeva, Revolution in Poetic Language; Kristeva, Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1980); Stuart Hall, ed., Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (London: Sage, 1997), 15–64, esp. 28–29; Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London: Routledge, 1979); I have deployed it in several previous essays on hermeneutics.

[64] The position articulated here has much in common with the approach to language and meaning known as usage-based constructionist perspective in linguistics, for a provocative recent example, cf. Adele E. Goldberg, Explain Me This: Creativity, Competition, and the Partial Productivity of Constructions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019). Cf. also J. Marshall Unger, “Emotion, Reason, and Language: Meanings Are Made, Not Retrieved,” Sino-Platonic Papers 287 (2019).

[65] My thanks to my colleague Mary Marshall, who pressed this (friendly) question at an earlier presentation of this argument.

[66] Doing What Comes Naturally: Change, Rhetoric, and the Practice of Theory in Literary & Legal Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1989), 313-467.

[67] But also, importantly, in music, film, liturgy, and so on.

[68] Similarly, Breed concludes Nomadic Text by summarising his argument that “reception history is nothing if it is understood as analyzing that which comes after the original. There is no such thing, since there was nothing entirely original in the first place. But by that same token, everything is then reception history if it is understood as analyzing how un- original texts manifest unoriginal meanings” (pp. 204–205). Such a vision of reception history admirably complements sensuous hermeneutics.