David Tombs

david.tombs@otago.ac.nz

Abstract

Recent work in biblical studies has given increased attention to a reading of Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse. This article explores how the stripping of Jesus might be understood as an example of abuse ‘hidden in plain sight’. Most students are initially surprised or doubtful when it is suggested that Jesus is a victim of sexual violence. However, this scepticism can become a powerful learning resource if they are helped to ‘discover’ it for themselves through an experiential learning process. This might involve a critical examination of crucifixion and stripping images, and/or a contextual bible study on Matthew 27:26–31. Discovering the sanitising and erasure of sexual violence in the dominant (mis)understanding of crucifixion can offer students insight into other ways that past and present sexual violence is often marginalised, normalised, or hidden. Often these classroom exercises prompt a discussion of what makes abuse ‘sexual abuse’.

Keywords

Jesus; Sexual Abuse; Crucifixion; Francisco Goya; Susan Sontag

1. Background

I developed a keen interest in liberation theologies during my undergraduate studies at Oxford and my Master’s at Union Theological Seminary, New York in the 1980s. In 1993, I began a part-time PhD at Heythrop College, University of London, to investigate Christology within Latin American liberation theology. I initially planned to investigate the development of liberationist Christology from the 1970s to the 1990s with particular reference to Jon Sobrino’s work in El Salvador. I found Jon Sobrino’s reading of Christ in light of ‘the crucified people’ of El Salvador (the Saviour) especially inspiring.[1] Sobrino’s life and work took seriously the inequality, social injustice and oppression which was the daily experience of the Salvadoran poor. He described how crucifixion of the Salvadoran poor was an ongoing reality. The poor were ‘crucified’ by relentless unjust economic structures. This was a slow and grinding crucifixion. If they sought to challenge or change these structures were met with harsh repression and political violence by the social elites and the military. This was a sudden and brutal crucifixion. In response to these two forms of crucifixion, Sobrino offered a powerful theology of solidarity with the crucified people of the world. He stressed the importance of taking crucifixion seriously in the present day, and spoke of ‘taking the crucified down from the cross’ as a focus and urgent challenge for Christian faith.

After a visit to El Salvador in the summer of 1996, I read an account of a particularly graphic sexualised execution of a health worker during the war in El Salvador in the early 1980s.[2] The execution included two features which I later came to realise were common in many torture practices. First, the extremity of the violence was a way to intimidate and threaten a wider audience. It was an intentional form of state terror. Second, the sexualised nature of the act was not a strange incidental detail but was an integral part of the intention to terrorise. Sexualised violence and sexual abuses are very common in torture practices. Rape and other abuses are commonly used to humiliate and degrade both male and female victims, and can be a devastating instrument of state terror.

To gain a deeper understanding of the impact of torture and sexual violence on the ‘crucified people’ in Latin America I started to read torture reports documenting the authoritarian regimes in the 1970s and 1980s. Looking at the common practices and patterns in the reports made me wonder how the state terror and sexual abuses of torture might shed light on the crucifixion narratives presented in the gospels. Could more recent torture and execution narratives from Latin America illuminate Roman practice and biblical narratives?

My article ‘Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse’ (1999) was an attempt to answer this question.[3] It sought to show the value of the Latin American liberationist approach to reading the bible in light of a concrete social context. It argued that Latin American torture reports could illuminate elements in the biblical narratives which might otherwise be easily missed. It concluded that Jesus was a victim of sexual abuse, since Mark and Matthew are explicit that he endured repeated stripping and exposure and this was intended as sexual humiliation. It also discussed the further possibility that Jesus might have suffered some additional form of sexual assault which the texts do not immediately disclose.[4]

Since publishing the article, I have had opportunities to work with students in the United Kingdom, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, and elsewhere, on how they respond to reading Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse. Other scholars, working independently and in different contexts, have also written on this neglected element in the crucifixion narrative.[5] The next section describes two preparatory exercises to introduce this work into a classroom. This is followed by a presentation of two classroom approaches (an image-based approach and a contextual bible study) that can be used either individually or in combination to explore the sexual violence of crucifixion. The final section suggests how reading crucifixion in terms of sexual violence, and noticing the silences and stigma around this, might develop critical awareness and offer opportunities for activism.

2. Preparatory Work

It is important to start with appropriate trigger warnings for what will come. Students should be encouraged to exercise self–care as well as being informed of available support. I explain that students can talk with me further about any of the issues raised if they wish to do so, and I make available a location specific support sheet for anyone who wishes to access confidential support. If I am visiting another institution, I try to discuss this in advance with my hosts, to ensure that support will be available if needed. The publicity for an event can be used to give a clear indication that the subject material might be challenging and potentially distressing so people attending a public event are warned in advance. Likewise, for students in a class setting, the potential sensitivity can be signalled in advance in the course outline or syllabus, and a reminder can be given the week before. Sometimes, at the very start of the session, I ask if anyone has reservations on what the topic might cover. If anyone raises potential concerns, we take time to discuss these first, and this can provide reassurance for the student who raised the concern as well as for others who might have been hesitant to speak.

a. Initial classroom discussion

To promote an experiential process and support self-reflection, an initial exercise can be used to gauge student responses to the suggestion that Jesus was a victim of sexual abuse. One way to do this is to write the confronting statement ‘Jesus was a victim of sexual abuse’ on a PowerPoint slide (or writing it on a whiteboard or chalkboard). Students are then asked to reflect on their response to this statement, and to consider both their thinking and their feelings. They are encouraged to take a few minutes to make a mental note of their own first responses, and then to think about possible reasons behind this. They do not need to write anything down but they are welcome to write down their responses if they wish to do so. It is likely that any group will have students who have personally experienced different forms of sexual violence, and it is helpful to signal at the outset than nobody will be expected to share their responses unless they wish to do so.

After a couple of minutes, if any students are willing to share their thoughts with the group it is always interesting to hear these. But I always reinforce that this sharing is a voluntary and it is fine if students prefer to keep their responses to themselves. This helps students to focus on how they do actually respond, rather than worry about how they ‘should’ respond, or what might be ‘correct’ to share with others. The intention is to help students to attend to their own actual response and to reflect on why this might be the case.

Students may find the statement strange and the invitation to respond to it perplexing. The initial sense of surprise might be because it is so rare to give any serious thought to Jesus in connection with sexual issues. The controversy around films like The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) show that linking Jesus to sex can generate strong feelings, negative responses and accusations of blasphemy. The invitation to think of Jesus in relation to sexual abuse may therefore come as an unexpected bolt out of the blue. Sometimes students ask for further direction, or want to double-check they have heard correctly. They might ask ‘What exactly are you asking us to do?’. If students ask for further guidance on what form a response might take, the three broad categories of ‘positive, neutral, or negative’ responses can be offered as one-word responses to show how students might position themselves in relation to the statement. Students can be asked whether they see the statement as something positive, neutral or negative, and why. If they can elaborate in more detail beyond positive, neutral, or negative, then so much the better.

For most students the statement ‘Jesus was a victim of sexual abuse’ is a new idea to them and they have never thought about this possibility before. However, if students have heard the idea before they can be encouraged to think back to how they responded when they first heard it, as well as how they respond now, if they wish to include this. Depending on the group, and how well they know each other, if the majority of students prefer to keep their thoughts to themselves a second question can be added to promote class discussion before moving on. After asking students about their own response, they can be asked to think of how others might respond to this statement. For example, how do they think members of their peer group, or family, or religious community might react. Students are usually quite happy to say what other people would think or say, and to hear what other students say on this, without needing to name any individuals or disclose their own personal views.

Common response examples include: That is a really strange suggestion! Did I read/hear/understand that correctly? How could such a reading of Jesus be true? What historical or textual evidence could be offered to support it? Why are we doing this, is it to be provocative? Isn’t this likely to be really offensive to some people? I would believe this if there was evidence for it, but it sounds like it is reading something into the text that is not there, so what is the point?

Rather than comment on these responses immediately, I usually simply thank the group and make a note of what was said for later, with the promise that we will come back to them in due course and a reminder to students to remember what they thought and felt. Depending on the time available one might then turn to the work in the next section on images of crucifixion and stripping, and/or the contextual bible study. However, if there is sufficient time, there is a further exercise that can be helpful preparation before moving on to these.

b) Hidden in Plain Sight

The cover image for Susan Sontag’s book Regarding the Pain of Others offers a helpful example for thinking about how sexual violence can be hidden in plain sight.[6] After a brief reminder on the sensitivity of the material that will be shown, we start by looking at the cover to Regarding the Pain of Others projected on screen. Students are invited to look at it for themselves and then say what they see, to make it easier to focus on the image the original etching by Francisco Goya (1746–1828) can be projected.

It shows a man hanging by a rope noose from a truncated tree branch. Another man, in military dress, is sitting and leaning backwards a few feet away. He is shown looking up at the hanging man, as if admiring the scene. In the background of the original etching there are two further figures hanging from tree branches to the left of the main figure. However, neither of these more distant hangings features in the version on Sontag’s book cover, only the two main characters at the front of the image are shown in the cropped version of the image on Sontag’s book.

Later in the book Sontag explains that the image is one plate in a numbered sequence of over 80 print etchings, The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra), which Goya created between 1810 and 1820.[8] The scenes depict atrocities against civilians committed by Napoleon’s forces during the Peninsular War in Spain (1808–1814). Sontag’s cover image is plate 36 in the sequence. Goya captioned each image with a title, and number 36 is titled ‘Nor this’ or ‘Not here either’ (Tampoco).[9]

When students are asked what they see, they typically mention the man hanging from a noose, and some also comment on the man looking up at him, and may also note the observer’s unusual pose and facial expression.

Sontag explains that ‘Goya’s images move the viewer close to the horror.’[10] She writes: ‘The ghoulish cruelties in The Disasters of War are meant to awaken, shock, wound the viewer’. [11] She also comments on the juxtaposition of the images with the captions, and notes a strange tension these create between looking and not looking:

The account of war’s cruelties is fashioned as an assault on the sensibility of the viewer. The expressive phrases in script below each image comment on the provocation. While the image, like every image, is an invitation to look, the caption, more often than not, insists on the difficulty of doing just that. A voice, presumably the artist’s, badgers the viewer: can you bear to look at this? One caption declares: One can’t look (No se puede mirar).[12]

Yet despite Sontag’s focus on Goya’s attention to horror and suffering she makes no mention of the hanging man’s apparent state of undress. She does not discuss, or even note, that his trousers are pulled down beneath his long shirt. One reason this can be missed is that the eye of the viewer is drawn upward to the head of the hanging man, the sawn-off tree branch, and the noose. This is also where the other man in the picture appears to be looking, and it is easy to follow his gaze. The words of the book title serve also serve to draw the eye away but in a different direction. The wording descends down to the bottom-right corner of the page. However, looking towards the bottom left corner of the cover, and focussing on the details and not just on what is immediately obvious, it is clear that the hanging man’s trousers have been pushed down to beneath his knees. Although his upper legs are covered by his long shirt there is no question that he is a state of undress.

Even if the image is left on screen for a while, the man’s undress tends to go unnoticed or at least unremarked. It is possible that some students might notice it but not comment upon it, and often when it is explained there are one or two nods in a group as if this confirms what some were thinking but did not say. For most groups, however, the majority of students are surprised when this is pointed out, and many are puzzled that they did not see it.

Other images in the sequence show that Goya was fully aware of how sexual violence could be used in war to mock and humiliate. For example, plate 33 ‘What more can be done?’ (Qué hai que hacer mas?) shows two soldiers holding apart the legs of an upturned and naked male captive, whilst a third soldier slices his sword down into the captive’s crotch.[13] Following plate 36 are a number of particularly disturbing images. Plate 37 shows a corpse impaled on a tree trunk with the caption ‘This is worse’ (Este es peor), which suggests a clear connection with the hanging man in plate 36.[14] Plate 39, ‘Great feat! With dead men!’, (Grande hazaña! Con muertos!) shows three naked male corpses on a tree, one of which is dramatically dismembered.[15] Depending on the group, these other images might be displayed or just mentioned without being shown.

The hanging man’s state of undress in plate 36 may often go unnoticed because sexual violence against men in conflict has received much less attention than sexual violence against women.[16] Even when there are obvious clues suggesting sexual violence, such as a state of undress, they are often missed when the victim is male because the viewer (or reader) does not come to the scene with this expectation. However, the likelihood of noticing the violence in plate 36 increases significantly if it viewed alongside plates 33, 37 and 38, which encourage the reader to consider sexual violence. In addition, earlier in the sequence, there are a number of plates depicting the rape of women. In plate 9, ‘They do not want to’ (No quieren), an elderly woman with a knife is shown coming to the defence of a younger woman who is being assaulted by a soldier. This is followed by plate 10, showing the rape of at least two women, with the same caption as plate 36 (Tampoco), which might be translated in this case as ‘Nor do they’. The repeated caption in plate 36 and plate 10 might help viewers of the whole series to give more attention to the man’s undress in plate 36, but most readers of Sontag’s book are unlikely to have this wider context in mind when they look at the cover. The violence, or at least the clear suggestion of it, remains ‘hidden in plain sight’.

A viewer may look at the book’s cover image many times yet fail to notice signs of sexual violence. However, in my experience, once the signs have been seen, they are likely to remain clear to the viewer. The viewer becomes aware of the scene in a new way, and sees both what is familiar and what is easily missed. The signs of sexual violence are therefore unlikely to revert back to being hidden once they have been recognised. Instead, when they have been noticed, they become some of the most noticeable elements of the scene even if they stay hidden to other viewers.

Viewing Sontag’s cover page can allow students to go through the process of personally discovering something hidden in plain sight. It is more useful to personally experience the process than to just hear about it. When it is a class activity it is rare for more than one or two students to notice the man’s undress until this is pointed out. The majority of students therefore have a direct experience of not seeing, and then seeing, what is in front of them. Those who were able to see it from the outset have a sense of how common it is for others to not see what they can see even when looking at the same scene. In both cases, the activity makes the idea of ‘hidden in plain sight’ more meaningful for the class. It shows how easy it is to miss what should be noticed, and opens the way to further activities which explore how the stripping and crucifixion of Jesus are usually depicted in ways that obscure the sexual element.

3. Classroom activities to explore the sexual violence of crucifixion

Once the preliminary exercises have been completed, class activities can move on to a more direct focus on crucifixion.[17]

a. Images of crucifixion and stripping

Most images of crucifixion in western art present a fairly formalized scene.[18] In most cases Jesus is nailed (or sometimes tied) to a Latin cross. The cross is made up of an upright and a crossbeam, and the crossbeam is affixed to the upright a little way down from the top. Jesus hangs with arms outstretched on the crossbeam. His legs hang down together, and his feet are fixed to the upright. He is without most of his clothing but usually wears some form of loincloth.

The scene has been depicted so often in Christian art that there is no shortage of images that can be used in a classroom as illustrations. Starting a discussion with some examples of these can help illustrate what is already quite familiar to students. It can also show some minor variations, such as a platform beneath the victim for him to stand on. If the preparation work included looking at Goya’s work, then looking at Goya’s representation of crucifixion ‘Cristo en la cruz’ may be of particular interest.

This and other more conventional images of crucifixion can then be viewed alongside less common depictions, some of which might raise questions about sexual violence. For example, students might discuss how much the loincloth in Goya’s ‘Cristo en la cruz’ influences the viewer. How does this image look when viewed alongside Michelangelo’s crucifix sculpture in the church of Santo Spirito, Florence?

Showing an image of a fully naked Jesus, such as Michelangelo’s can open up a lively classroom discussion. Michelangelo’s sculpture follows most of the common conventions but, at least in its present form, it does not have a conventional loincloth. A discussion can start with a relatively straightforward question on whether this is the first instance that students have seen a fully image of Jesus on the cross (for some it usually is) or whether they have seen others. Where students have seen other images of a naked Jesus these can be considered as well. The frequency of depicting Jesus as fully naked, versus the frequency of depictions with a loincloth, can also be discussed. What the students see as the likely reasons for this can then be explored. The loincloth is not mentioned in the text, so why is it so common? The possibility that the statue might originally have had a loin cloth can also be mentioned, and students can be asked if this makes a difference to how they see it.

When the group are ready, discussion might then move to whether seeing Jesus naked makes them view crucifixion in a different way to conventional images, and what the reason might be for this. Is the naked Jesus more confronting than conventional depictions? Could there be even more confronting images than Michelangelo’s?

This can be a good opportunity to raise questions around enforced public nudity and sexual humiliation and sexual violence. In a classroom setting, this requires considerable care and sensitivity. It is good to remind students that, as indicated at the outset, some of the material will be sensitive and potentially disturbing. The students may have heard this at the outset, in the consideration of ‘hidden in plain sight’ but not have anticipated how the class might develop. The initial statement that Jesus was victim a victim of sexual abuse might have seemed far-fetched and not a serious suggestion, but viewing a naked Jesus on the cross can be more unsettling. Students may also be familiar with Christa images (female figures on the cross or presented as if crucified) and this can lead to a discussion on why Christa figures are often represented naked and whether there might be different social attitudes to female and male nudity.[21]

Alongside images of a naked Jesus on the cross, some images of the stripping of Jesus can also offer similar opportunities to re-think assumptions and perceptions. Most images of the stripping focus on the stripping at the cross, featured as the Tenth Station of the Cross, and just prior to the division of Jesus’ clothing. Most of these images follow a fairly standard convention. Jesus is rarely shown as fully naked and there are often only two or three people who are involved in the stripping. The stripping is sometimes downplayed, as if Jesus is being helped to undress, rather than being forcibly stripped. Examples of more gentle disrobing scenes can be shown in class, and these can begin an initial discussion of how well these images might fit with the reality of how a condemned prisoner would be treated and what they might leave out.[22] A variety of more forceful images of the stripping can be introduced, depending on how confronting these might be to a group.

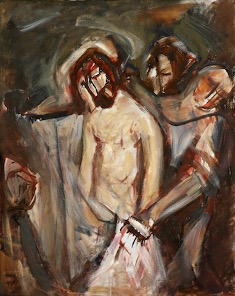

The Tenth Station of the Cross in St Peter’s church in Zagreb, Croatia (image 4), shows a sorrowful Jesus with two figures beside him, one to the right side next to him, and the other to the left and behind him. The facial expression of the figure beside Jesus, and the grip he has on Jesus clothing, suggest the forceful violence of the encounter and how this was experienced. Jesus is shown with his eyes shut, as if unable to watch. It is a useful image to compare with images of stripping that suggest a peaceful calm.

The Tenth Station at the Church of Holy Cross in Sisak, Croatia, (image 5) can also generate thoughtful discussion in a classroom. Jesus stands at the centre surrounded by an indeterminate number of others. The flurry of aggressive action is suggested in the way that different figures seem to blur into each as the clothing is pulled away with the clear suggestion that Jesus will be left fully exposed. The painting conveys the vulnerability of Jesus. He seems to be readying himself for when the cloak will be pulled away by screening his crotch with his right hand. His eyes appear to be closed, or near closed, as if he is unable to look.

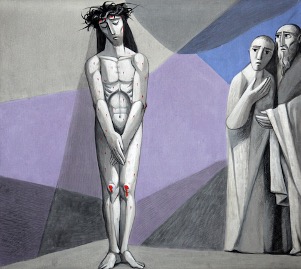

The Tenth Station at Church of the Holy Trinity, Gemünden am Main, Germany, offers a slightly different focus. This image features the aftermath of stripping rather than the stripping itself. Those who have stripped Jesus are not depicted, instead he is shown alone and apart. He stands slightly off-centre but nonetheless the focal point of the viewer’s gaze. In the absence of a loincloth, he seeks to shield himself with both his hands. In the background, and a few steps away from the isolated Jesus, two onlookers join the viewer in surveying the scene. Their facial expressions and hand gestures suggest they do not know how to react or respond to what they see. In this, perhaps they serve a similar purpose as Goya’s captions by conveying a message to the viewer. What they see is confronting and difficult, and they signal that the viewer is likely to feel likewise.

Discussing images like this can help students to think more critically about the way the stripping of Jesus is commonly portrayed, and how the element of sexual violence is so readily downplayed or sanitised in more traditional versions. One of the points that might be made in this discussion is that nearly all the images of stripping in Christian iconography focus on the stripping at the cross. This is the final stripping, as featured in the traditional Tenth Station of the Cross, which has an important role in Catholic (and some Anglican) devotional traditions. John 19:23 suggests that at this point the clothes of Jesus were divided between into four parts, with a part for each soldier. Representations of the scene in art do not always show that it is soldiers who strip Jesus, but they do invariably suggest that it is only a few people, typically two or three. Students can be invited to contrast this stripping with earlier strippings of Jesus. A close reading of the Mark 15:15–24 and Matthew 27:26–31 suggests that the stripping in the praetorium was a much more dramatic affair. It is said that the ‘whole cohort’ was gathered (Mark 15:16, Matt. 27:27). Students are often surprised that this was not just a few soldiers but more to have been 400–500 soldiers.[23] What would this look like it if was depicted? How might it challenge a viewer’s sense of what was happening? The absence of images of the stripping of Jesus in front of the cohort in the praetorium,in comparison to the many images of the stripping at the cross, is a further example of how selective depictions of the stripping in western art have been.

b) A Contextual Bible Study on Matthew 27:26–31

A second way to approach the sexual violence of the stripping of Jesus in the classroom is through a close reading and discussion of the text. The contextual bible study (CBS) on the crucifixion of Jesus, developed by the Ujamaa Centre, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), provides a good way to do this.

The Ujamaa Centre began its activism work during the anti-apartheid struggle and is known for its community-based participatory bible studies.[24] One of the best known of these is the Tamar CBS (2 Samuel 13:1–22) which was originally developed in 1996 to explore rape and violence against women, and built on Phyllis Trible’s well-known work Texts of Terror (1984).[25] Other CBS address a wide range of important social issues ranging from youth, family, community, economics, land, food, justice, HIV/AIDS, and much else. A CBS will typically immerse a group in a ‘slow reading’ of a biblical passage. A sequence of questions and discussions guide the group as they look at the narrative with close attention to detail. This gives the group opportunities to reflect on the text, to offer their own interpretation and address tensions and complexities, and to discuss the text’s relevance to their own situation.

In 2018, the Centre for Theology and Public Issues at the University of Otago hosted the biblical scholar Gerald West of UKZN, as a De Carle Distinguished Lecturer, for a lecture series on ‘The Bible as a Site of Struggle’.[26] West is well known for his work on contextual hermeneutics and his work with the Ujamaa Centre on contextual bible studies.[27] His time in New Zealand included a workshop at the Anglican Cathedral in Wellington on the Tamar CBS (10 March 2018).[28]. The previous evening, I presented a public Lenten Lecture at the cathedral titled ‘When Did We See You Naked?’ on the stripping of Jesus.[29]

Hosting these two events together confirmed the value of undertaking further collaborative work. The Lenten Lecture was the first time I used an excerpt from the HBO television series Rome to consider what being stripped in front assembled soldiers might involve. The show features the stripping of Vercingetorix, in front of Caesar and his assembled soldiers, following the defeat of the Gauls at the battle of Alesia (52 BCE).[30]

A fortnight later, Katie B Edwards and I published a short piece titled ‘#HimToo – why Jesus should be recognised as a victim of sexual violence’ which included a link to the Vercingetorix stripping in Rome.[31] This short piece on the online platform The Conversation prompted a lively debate on whether or not Jesus should be viewed as a victim of sexual abuse, and underlined the need for more attention to the stripping of Jesus in biblical studies.

In 2019, the Centre for Theology and Public Issues and the Ujamaa Centre began a collaborative research project to develop a CBS on the stripping of Jesus, as a way to address sexual violence.[32] A research grant from the University of Otago allowed me to make two visits to South Africa in 2019. During the first visit, in June 2019, I presented a public lecture on ‘The Stripping of Jesus: Sexual Violence Hidden in Plain Sight’ looking at Matthew 27:27–31.[33] The following day, community activists, students, and staff, were invited to an Ujamaa workshop led by Gerald West and Charlene van der Walt to develop a CBS response. After further discussion on some of the issues raised by the lecture, about twenty workshop participants split into four small groups to discuss and draft a contextual bible studies on either Mark 15:15–24 or Matthew 27:27–31.[34] Most groups chose the Matthew passage:

26 Then Pilate released Barabbas for them; but after having Jesus scourged, he handed Him over to be crucified.

27 Then the soldiers of the governor took Jesus into the Praetorium and gathered the whole Romancohort around Him.

28 They stripped Him and put a scarlet robe on Him.

29 And after twisting together a crown of thorns, they put it on His head, and a reed in His right hand; and they knelt down before Him and mocked Him, saying, “Hail, King of the Jews!”

30 They spat on Him, and took the reed and beganto beat Him on the head.

31 After they had mocked Him, they took the scarletrobe off Him and put His owngarments back on Him, and led Him away to crucify Him.

(American Standard Version 1995)

At the end of the day, the groups shared their drafts with those present. Ideas from the different groups were subsequently consolidated into a single CBS on Matthew 27:26–31, with the title ‘The stripping of Jesus as sexual violence/sexual abuse: Constructing a CBS’. This initially included seven questions:

- Listen to a ‘slow’ reading of Matthew 27:26-31 in a number of different translations and languages. What have you heard from this slow reading of a well-known story that disturbs you?

- Who are the characters in this story, and what do we know about each of them?

- How many times is Jesus stripped? Matthew makes it clear that Jesus was stripped more than once. Re-read the text carefully and identify how many times Jesus is stripped.

- Matthew also makes it clear that Jesus was stripped in front of a whole ‘cohort’ of about 500 soldiers. What other forms of sexual abuse might have taken place when so many men were involved in the repeated stripping and beating of Jesus?

- In what situations in your context are men sexually abused by other men?

- Are there resources in your community to address male sexual violence against men?

- What can we do to address the issue of male sexual violence against men? Devise a specific ‘action plan’ of an action that you can participate in.

During the following semester, West and Van der Walt co-taught a UKZN class on ‘Religion and Gender’. As one of the class assignments, students facilitated the CBS on the stripping of Jesus with an external group of their choice. Students then submitted a written assignment on how they approached the task, their experiences facilitating the group, and the responses that they had encountered.

When I made my return visit in October 2019, students made an oral report on what they had learned from the course, including the CBS experience. Hearing their responses was particularly instructive on how the CBS was received by others. A number of students mentioned the initial efforts required to find participants willing to do the bible study. Some groups were intrigued and enthusiastic about what might be involved, but others were wary and cautious. Some students spoke of the initial scepticism and resistance that greeted the suggestion.

It was also interesting to hear more about which parts of the discussion some group found difficult and how language and translation could impact on this. For example, some of students who had conducted the bible study in isi-Zulu had confronted strong reactions to the term ‘stripping’, since it implied a level of force and violence. Some participants found this shocking, and even offensive, so it required careful facilitation. However, although this could be confronting it also created a positive opportunity. It opened the door to discussions on what the stripping in the Greek text really involved, and whether it might get missed in English versions of the text.

In light of the student experiences and insights, the CBS discussion questions were further considered and refined. The title was changed to ‘A Contextual Bible Study on the Crucifixion of Jesus: Engaging the issue of male violence against men’.[35] The initial seven questions were expanded to ten. The additional questions scaffolded the discussion around potentially sensitive issues more carefully, and nuanced some of the steps a bit further. In the revised version the questions became:

- Listen to a ‘slow’ reading of Matthew 27:26–31 in a number of different translations and languages. What have you heard from this slow reading of a well-known story that disturbs you?

- Who are the characters in this story, and what do we know about each of them?

- What forms of violence are used against Jesus?

- Is stripping a man a form of violence? Why do the soldiers strip Jesus?

- How many times is Jesus stripped? Matthew makes it clear that Jesus was stripped more than once. Re-read the text carefully and identify how many times Jesus is stripped.

- Is the repeated stripping of Jesus a form of ‘sexual abuse’? Discuss in your group what you mean by ‘sexual abuse’?

- Matthew also makes it clear that Jesus was stripped in front of a whole ‘cohort’ of about 500 soldiers. (The Romans often used sexual violence to humiliate those they conquered and ruled.) What other forms of ‘sexual abuse’ might have taken place when so many men were involved in the repeated stripping, beating, and humiliation of Jesus?

- In what situations in your context are men sexually abused by other men?

- Are there resources in your community and church to address male sexual violence against men?

- What can we do to address the issue of male sexual violence against men? Devise a specific ‘action plan’ that you can participate in that will help address the issue of male sexual violence against men?

The revised CBS is seen as a work in progress. It will be refined and revised further in light of experience. Working with the staff and students at UKZN students on this process as a form of classroom activism has been a great privilege and learning experience.

4. Surfacing Stigma

If the preparatory classroom activity started with the discussion exercise on the statement ‘Jesus was a victim of sexual violence’ then it is possible to go back to the initial discussion after completing the images work and/or the bible study. This can be a valuable step to allow for experiential learning in addition to critical analysis.

I ask students to recall to themselves their own responses and/or how they thought other people might respond. I might ask about any positive responses the students had, or expected others might have, and the reasons for this. As with earlier discussion, these responses can be shared aloud if students are willing, but there is no need for students to disclose anything they prefer to keep to themselves, and it is good to re-state this as a reassurance. The primary purpose is to help students process their own thoughts.

I then ask whether any of the material (Plate 36 from Disasters of War, or any images of crucifixion or stripping, or Matthew 27:26–31 changed this. If so, what accounts for the change? Then I would ask more about any negative reactions. Students are rarely surprised when they are told that the claim that Jesus was a victim of sexual abuse usually draws sceptical and often dismissive or hostile reactions. I ask students to reflect on whether they themselves initially felt any negative reactions, or if they anticipated negative reactions from others. If so, what might have been behind these negative responses? As before, students can be given opportunities to share their thoughts without being pressured to do so. It is their own self-reflection which is important, not what they say aloud.

If the group seem receptive, there may be an opportunity to open up a discussion on sexual violence and stigma. Sexual violence often carries a heavy stigma, which can be devastating for social standing and self-worth. In his oft-cited work, Erving Goffman describes stigma as a ‘spoiled identity’.[36] This is often conveyed in negative responses to survivors from wider society, and is easily internalised as low self-worth by survivors.[37] Stigma, and assumptions about damage to social standing, appear to be a key factor in negative responses to naming Jesus as victim of sexual violence.[38] In class discussions, students often indicate they see stigma as a factor in negative responses. Often the stigma is so pervasive that it is not even named when students first think about reactions, it is taken as so self-evident and unavoidable that it can be taken for granted and not even named. When the stigma is not explicitly named it can remain unexamined and unchallenged. So it is helpful to help students to ask students to think more about this part of a response to sexual violence.

On reflection, students invariably feel the attachment of stigma to those who experience sexual violence is unfair and misplaced. This can open a conversation on why this reaction is nonetheless so common. Furthermore, some students even recognise that the stigma towards sexual violence is not just a negative response that other people have, but something that they themselves might have internalised at some level. Students might not have believed this about themselves if it had simply been asserted from the outset, but the classroom process can help students to come to this conclusion for themselves, through reflection on their own initial responses to the sexual abuse of Jesus. Just as discovering violence hidden in plain sight can be more powerful than just hearing about it, so a classroom encounter with assumptions and values that students may not previously have recognised, can offer a powerful opportunity for transformative learning.

5. Conclusion

One of the reasons for looking at the crucifixion as a form of sexual violence is that it can make a practical difference to how sexual violence is viewed. Students can draw upon work on Jesus as a victim of sexual violence to make connections with how sexual abuse/violence operate in other contexts. How might other examples of sexual abuse/violence remain hidden in plain sight? How do they stay hidden and how can they be recognised? What difference does it make when it becomes known and named appropriately? To what extent are perceptions of sexual violence in church and society governed by misplaced attitudes to stigma? How can these negative attitudes be challenged and changed?

The answers to these questions will vary from context to context. Likewise, the classroom opportunities for moving beyond better awareness to directly promoting activism will vary from place to place. In some contexts, awareness may be a more appropriate classroom goal than activism, at least as a first stage. Classroom discussions might promote awareness of the issue, and also awareness of the important contribution that activism can make to it, without necessarily committing to activism as a classroom activity. In some institutions, especially when engagement with sensitive material and topical issues is viewed with concern or even suspicion, framing classroom activities primarily in terms of awareness may be a prudent option. However, wherever possible, there are even greater learning opportunities when students are encouraged to move from awareness to activism. Linking practical activism to critical reflection in the classroom offers greater opportunities for practical learning. One of the inspiring examples of work at the University of KwaZulu-Natal was the integration of classroom work with practical activism.[39]

Reading Jesus as victim of sexual violence offers extraordinary potential for building awareness on sexual violence. In particular, the biblical texts can be used to show how readily sexual violence is hidden in plain sight, and how strongly stigma impacts on attitudes to sexual violence. Acknowledging Jesus in this way can draw sceptical and often dismissive or hostile reactions. However, these responses often yield excellent classroom opportunities to go beneath superficial understanding and attitudes and to address more deeply rooted stigmas in both the churches and wider society.

Works Cited

Burgess, Kaya. “#HimToo: Jesus was a sex abuse victim, say scholars,” The Times (27 March 2018); https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/himtoo-jesus-was-sex-abuse-victim-say-scholars-5lmx3cg58.

Clague, Julie. “The Christa: Symbolizing My Humanity and My Pain,” Feminist Theology 14:1 (2005): 83–108.

Edwards, Katie B. and David Tombs, “#HimToo – why Jesus should be recognised as a victim of sexual violence,” The Conversation (23 March 2018); https://theconversation.com/himtoo-why-jesus-should-be-recognised-as-a-victim-of-sexual-violence-93677

Everhart, Ruth. Ruined. Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House, 2016.

Gafney, Wil. “Crucifixion and Sexual Violence,” HuffPost (28 March 2013); https://www.huffingtonpost.com/rev-wil-gafney-phd/crucifixion-and-sexual-violence_b_2965369.html.

Goffman, Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York and London: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

Golden, Renny and Michael McConnell. Sanctuary: The New Underground Railway. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1986.

Goldsworthy, Adrian K. The Roman Army at War: 100 BC–AD 200. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Harries, Richard. The Passion in Art. Ashgate Studies in Theology, Imagination and the Arts; Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate 2004.

—– The Image of Christ in Modern Art. Farnham, Surrey; Burlington VA: Ashgate, 2013.

Harley-McGowan, Felicity. “Picturing the Passion.” Pages 290–307 in Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art. Edited by Robin M. Jensen and Mark D. Ellison. New York and London: Routledge, 2018.

Heath, Elaine A. We Were the Least of These: Reading the Bible with Survivors of Sexual Abuse. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2011.

Jensen, Robin Margaret. Understanding Early Christian Art. New York and London: Routledge, 2000.

Parker, H. M. D. The Roman Legions. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928.

Raynor, Vivien. “Goya’s ‘Disasters of War’: Grisly Indictment of Humanity,” New York Times (25 February 1990): CN.12.

Reaves Jayme R. and David Tombs, “Shiloh Lecture: #MeToo Jesus: Why Naming Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse Matters,” Sheffield Institute for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies, University of Sheffield (16 January 2018); http://www.shilohproject.blog/video-recording-of-metoo-jesus-why-naming-jesus-as-a-victim-of-sexual-abuse-matters/.

—– “Acknowledging the Sexual Abuse of Crucifixion: #MeToo as an Invitation to a New Conversation,” Queen’s Ecumenical Theological Foundation, Birmingham (17 January 2019).

—– “#MeToo Jesus: Naming Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse,”International Journal for Public Theology 13.4 (2019): 1–26.

Slee, Nicola. Seeking the Risen Christa. London: SPCK Publishing, 2011.

Smith, Christian. Resisting Reagan: The U.S. Central America Peace Movement. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1996.

Sobrino, Jon. Jesus the Liberator. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books; Tunbridge Wells, Burns & Oates, 1993.

—– The Principle of Mercy: Taking the Crucified People from the Cross. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1994.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Giroux and Strauss, 2003.

Stemple, Lara. “The Hidden Victims of Wartime Rape”, New York Times (1 March 2011): A.25.

Tombs, David. “The Hermeneutics of Liberation.” Pages 310–55 in Approaches to New Testament Study. Edited by Stanley E. Porter and David Tombs. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995.

—– “Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse.” Union Seminary Quarterly Review 53 (Autumn 1999): 89–108; http://hdl.handle.net/10523/6067.

—– Latin American Liberation Theology. Religion in the Americas Series Vol. 1; Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2002.

—– Unspeakable Violence: Reading the Crucifixion in the Light of the Truth Commission Reports for El Salvador and Guatemala. Unpublished PhD, Heythrop College, University of London, 2004.

—– “Lord When Did I See You Naked”, Anglican Taonga (Winter 2018): 22–23; https://issuu.com/anglican_taonga/docs/taonga_winter_2018_web_1/22

—– Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse: Text and Context. Dunedin: Centre for Theology and Public Issues, University of Otago, 2018; http://hdl.handle.net/10523/8558.

—– “Confronting the Stigma of Naming Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Violence.” Pages 71–86 in Enacting a Public Theology. Edited by Clive Pearson. Stellenbosch: SUNMeDia, 2019.

Trainor, Michael. Body of Jesus and Sexual Abuse: How the Gospel Passion Narrative Informs a Pastoral Approach. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2014.

Ujamaa Centre for Community Development and Research. Doing Contextual Bible Study: A Resource Manual. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2014.

Van der Walt, Charlene. “Is There a Place for Protest in Pedagogy? Engaging the Silencing Effects of Gender Based Violence within the Context of Theological Education,” in “Space and Place: Theological Perspectives on Living in the World,” Fifth Consultation of the Global Network of Public Theology, Bamberg, 23-26 September 2019.

West Gerald O. The Stolen Bible: From Tool of Imperialism to African Icon. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

West Gerald O. and Phumzile Zondi-Mabizela, “The Bible Story that Became a Campaign: The Tamar Campaign in Africa (and beyond),” Ministerial Formation 103 (2004): 4–12.

—– “Jesus, Joseph, and Tamar Stripped: Trans-textual and Intertextual Resources for Engaging Sexual Violence Against Men.” In “When Did We See You Naked?”: Acknowledging Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse. Edited by Jayme R. Reaves, Rocío Figueroa, and David Tombs. London: SCM Press, in preparation for 2021.

Zalewski, Marysia, Paula Drumond, Elisabeth Prügl, and Maria Stern, eds., Sexual Violence Against Men in Global Politics.New York: Routledge, 2018.

Zarkov, Dubravka. The Body of War: Media, Ethnicity and Gender in the Break-up of Yugoslavia. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

[1] See especially, Jon Sobrino, Jesus the Liberator (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books; Tunbridge Wells, Burns & Oates, 1993); Sobrino, The Principle of Mercy: Taking the Crucified People from the Cross (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1994). For a wider discussion of Latin American liberation hermeneutics, see David Tombs, “The Hermeneutics of Liberation,” in Approaches to New Testament Study (ed. S. E. Porter and David Tombs; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 310-55; David Tombs, Latin American Liberation Theology (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2002).

[2] Renny Golden and Michael McConnell, Sanctuary: The New Underground Railway (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1986), 64-65. I first read about it during 1997, in Christian Smith, Resisting Reagan: The U.S. Central America Peace Movement (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1996), 53. Sadly the name of the health worker who was killed is not preserved in these accounts. I had first visited El Salvador in 1988, following a graduate year at Union Theological Seminary, New Yok. I made a second visit to El Salvador in 1996, and reading the story so soon after this second visit made a strong impression. See further, David Tombs, Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse: Text and Context (Dunedin: Centre for Theology and Public Issues, University of Otago, 2018), 1; http://hdl.handle.net/10523/8558.

[3] David Tombs, “Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse,” Union Seminary Quarterly Review 53 (Autumn 1999): 89-108; http://hdl.handle.net/10523/6067.

[4] This argument became increasingly central to the PhD. When I finally submitted in 2004 the thesis had developed into a much fuller version of the central argument published in 1999; David Tombs, Unspeakable Violence: Reading the Crucifixion in the Light of the Truth Commission Reports for El Salvador and Guatemala (Unpublished PhD, Heythrop College, University of London, 2004).

[5] Elaine A. Heath, We Were the Least of These: Reading the Bible with Survivors of Sexual Abuse (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2011); Wil Gafney, “Crucifixion and Sexual Violence,”, HuffPost (28 March 2013); https://www.huffingtonpost.com/rev-wil-gafney-phd/crucifixion-and-sexual-violence_b_2965369.html; Michael Trainor, Body of Jesus and Sexual Abuse: How the Gospel Passion Narrative Informs a Pastoral Approach. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2014.

[6] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Giroux and Strauss, 2003); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regarding_the_Pain_of_Others#/media/File:Regarding_the_Pain_of_Others.jpg. Public Domain.

[7] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/334470 Public Domain.

[8] See Vivien Raynor, “Goya’s ‘Disasters of War’: Grisly Indictment of Humanity,” New York Times (25 February 1990), CN.12. The sequence is in three sections. Section 1 depicts the violence against civilians during the war (images 1-47). Section 2 shows the famine which followed (48-64). Section 3 shows the disillusion and frustration after the return of Ferdinand VII and Bourbon restoration. When the prints were first published in 1863, thirty-five years after Goya’s death, there were eighty images but a further two were added later.

[9] Plate 35 is captioned ‘One can’t tell why’ (No se puede saber por qué) shows a group of priests and peasants holding crucifixes; https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/381363 Public Domain. Placards hang from their necks describing their alleged crimes around their necks, but they are not legible to the viewer. The caption ‘Nor this’ (Tampoco) for plate 36 therefore suggests that the reason for the hanging is likewise unknowable.

[10] Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 39.

[11] Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 40.

[12] Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 40.

[13] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/381361. Public Domain.

[14] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/361848. Public Domain. The notes for this plate on the web page for the National Galleries Scotland indicate that it based on a real event that happened in 1808 at the town of Chinchón, where Goya’s brother served as the parish priest. The French army massacred every man they could find in response to the killing of two French soldiers; https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/34019/worse-esto-es-peor-plate-37-disasters-war-series

[15] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/381365. Public Domain.

[16] Dubravka Zarkov, The Body of War: Media, Ethnicity and Gender in the Break-up of Yugoslavia (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 155-69; Lara Stemple, “The Hidden Victims of Wartime Rape,” New York Times (1 March 2011), A.25; Marysia Zalewski et al., eds., Sexual Violence Against Men in Global Politics (New York: Routledge, 2018).

[17] Another exercise that can be used as preparation involves looking at an image by the artist Ghislaine Howard, in her series on ‘The Captive Figure’ (2000). However, for reasons of space this image will not be discussed here.

[18] See Robin Margaret Jensen, Understanding Early Christian Art (New York and London: Routledge, 2000); Richard Harries, The Passion in Art (Ashgate Studies in Theology, Imagination and the Arts; Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate 2004); Richard Harries, The Image of Christ in Modern Art. (Farnham, Surrey; Burlington VA: Ashgate, 2013); Felicity Harley-McGowan, “Picturing the Passion” in Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art (ed. Robin M. Jensen and Mark D. Ellison; New York and London: Routledge, 2018) 290-307.

[19] Francisco Goya, Museo Nacional del Prado, artchive.com; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christ_Crucified_(Goya)#/media/File:Cristo_en_la_cruz_(Goya).jpg

[20] Photo by Alexandra Korey, http://www.arttrav.com. Used with permission.

[21] Julie Clague, “The Christa: Symbolizing My Humanity and My Pain,” Feminist Theology 14:1 (2005): 83-108. Nicola Slee, Seeking the Risen Christa (London: SPCK Publishing, 2011).

[22] The image used to illustrate an article by Kaya Burgess in the Times is just one example of this; Kaya Burgess, “#HimToo: Jesus was a sex abuse victim, say scholars,” The Times (27 March 2018); https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/himtoo-jesus-was-sex-abuse-victim-say-scholars-5lmx3cg58

[23] A cohort was notionally 600 men; H. M. D. Parker, The Roman Legions (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928). In practice, the actual number was less than this. Goldsworthy explains that each legion was composed of 10 cohorts, and each cohort was sub-divided into six centuries. However, the ‘centuries’ typically comprised 80 men rather than 100, making a typical ‘full cohort’ 480 men; Adrian K. Goldsworthy, The Roman Army at War: 100 BC-AD 200 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 13-14. Some scholars suggest the number might be even lower. Losses during campaigns might further reduce a cohort’s numbers, but there is no reason to think that the cohort taken to Caesarea to ensure order at the Passover festival would have been significantly under strength.

[24] See Ujamaa Centre for Community Development and Research, Doing Contextual Bible Study: A Resource Manual (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2014).

[25] Gerald West and Phumzile Zondi-Mabizela, “The Bible Story that Became a Campaign: The Tamar Campaign in Africa (and beyond),” Ministerial Formation 103 (2004): 4-12; Ujamaa Centre, Doing Contextual Bible Study, 49-55.

[26] See https://www.otago.ac.nz/ctpi/projects/west.html

[27] Gerald O. West, The Academy of the Poor Towards a Dialogical Reading of the Bible (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999); The Stolen Bible: From Tool of Imperialism to African Icon (Leiden: Brill, 2016).

[28] The Tamar story was the first CBS developed by the Ujamaa Centre in 1996, and has been widely used in different contexts. In April 2018, West also led a Tamar CBS at the Pacific Theological College, Suva, as part of a project for the New Zealand Institute for Pacific Research.

[29] See David Tombs, “Lord When Did I See You Naked,” Anglican Taonga (Winter 2018), 22-23; https://issuu.com/anglican_taonga/docs/taonga_winter_2018_web_1/22. ‘When Did We See You Naked?’ is a collaborative project (2018–2020) by Jayme Reaves, Rocío Figueroa, and myself. The Lent Lecture built on a presentation Jayme R. Reaves and David Tombs, “Shiloh Lecture: #MeToo Jesus: Why Naming Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse Matters,” Sheffield Institute for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies, University of Sheffield (16 January 2018); http://www.shilohproject.blog/video-recording-of-metoo-jesus-why-naming-jesus-as-a-victim-of-sexual-abuse-matters/; and Jayme R. Reaves and David Tombs, “Acknowledging the Sexual Abuse of Crucifixion: #MeToo as an Invitation to a New Conversation,” Queen’s Ecumenical Theological Foundation, Birmingham (17 January 2019). See further, Jayme R. Reaves and David Tombs, “#MeToo Jesus: Naming Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse,”International Journal for Public Theology 13.4 (2019): 1-26.

[30] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xkl5ovfANO8&feature=youtu.be

[31] Katie B. Edwards and David Tombs, “#HimToo – why Jesus should be recognised as a victim of sexual violence,” The Conversation (23 March 2018); https://theconversation.com/himtoo-why-jesus-should-be-recognised-as-a-victim-of-sexual-violence-93677. Edwards is a Co-Director of the Shiloh Project and had hosted the Reaves and Tombs ‘#MeToo Jesus’ (January 2018) lecture. This article was picked up by newspapers and social media and attracted both positive and negative responses.

[32] This collaboration is described by West in Gerald West, “Jesus, Joseph, and Tamar Stripped: Trans-textual and Intertextual Resources for Engaging Sexual Violence Against Men” in “When Did We See You Naked?”: Acknowledging Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse (ed. Jayme R. Reaves, Rocío Figueroa Alvear, and David Tombs; London: SCM Press, in preparation for 2021).

[33] David Tombs, “The Stripping of Jesus: Sexual Violence Hidden in Plain Sight,” Ujamaa Centre Public Lecture (4 June 2019).

[34] See West, “Jesus, Joseph, and Tamar Stripped”. West helpfully suggested expanding the verses to be explored by adding the flogging in Mark 15:15 and Matt. 27:26.

[35] West explains that the title was intended to signal that the CBS focus was on male sexual violence against men. This was to avoid distracting conversations around female sexual violence against men, which is sometimes used to avoid discussion of male sexual violence against women; West, “Jesus, Joseph, and Tamar Stripped”.

[36] Erving Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (New York and London: Simon & Schuster, 1963).

[37] See, for example, Ruth Everhart, Ruined (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House, 2016).

[38] David Tombs, “Confronting the Stigma of Naming Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Violence”, in Enacting a Public Theology (ed. Clive Pearson; Stellenbosch: SUNMeDia, 2019), 71-86.

[39] See the paper by Charlene van der Walt, “Is There a Place for Protest in Pedagogy? Engaging the Silencing Effects of Gender Based Violence within the Context of Theological Education,” in “Space and Place: Theological Perspectives on Living in the World,” Fifth Consultation of the Global Network of Public Theology, Bamberg, 23-26 September 2019.