Gerald O. West and Sithembiso Zwane*

west@ukzn.ac.za; zwane@ukzn.ac.za

Abstract

Biblical studies in the School of Religion, Philosophy, and Classics at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa has been partially constituted by the community-based activism of the Ujamaa Centre for Community Development and Research over a period of more than thirty years. This essay reflects on a particular series of contrapuntal movements in which 1 Kings 21:1-16 has been interpreted within this interface of community-based activism and formal academic pedagogy, moving between Contextual Bible Study workshops with unemployed African youth and classroom-based learning with African undergraduate and postgraduate students. We give particular attention in this essay to how interpretive space is reconstituted through this intentional collaboration.

Keywords

Contextual Bible Study; 1 Kings 21; Land; Gender; Unemployment

Introduction

The ordering in our title is deliberate. Our university-based biblical studies pedagogy is shaped by our community-based Contextual Bible Study (CBS) activism. This movement between community and university is, of course, cyclical: classroom-based pedagogy draws on aspects of biblical studies scholarship that turn out to be useful for community-based CBS work. But the ordering is important, for it reflects the predominant orientation to our pedagogy. We seldom teach biblical studies material that we have not practised.

Our praxiological preference at the Ujamaa Centre is that we offer a Contextual Bible Study at the request of or summons by a local organised community-based social sector. This is how an earlier version of the 1 Kings 21 CBS (constructed in 2003) came about,1 as did the more recent version discussed in this article. “Contextual Bible Study” is a form of praxis in which the Ujamaa Centre for Community Development and Research re-reads an already present (and significant) Bible with and within particular organized communities of the poor and marginalized, recognizing that theological change is required for sustained-systemic social change in contexts where the Bible is a sacred site.2 Typically, the Ujamaa Centre is invited by a community-based or faith-based group to work with them on a particular contextually generated concern. In each case there is some recognition that the contextual concern has a theological component, which is why the group invites the Ujamaa Centre to work with it. In each case the group has its own local resources and makes use of a range of other available resources from its community-based networks. The collaborative contribution of the Ujamaa Centre, through CBS processes, is only one set of resources among others. But, if it is true, as we argue it is,3 that without theological change there can be no sustained social systemic change in communities where the Bible is a significant-sacred text, then CBS is a meaningful resource.

The work of CBS is collaborative work, with CBS structuring, through its See-Judge-Act processes,4 an interpretive alliance between what we prefer to refer to as “ordinary readers” and socially engaged biblical scholars.5 South Africans are wary of “non-“ language, so Teresa Okure’s term “non-scholar” has not been readily adopted,6 but it does capture rather well an important contribution of CBS to the interpretive alliance. The particular resources of biblical studies identify and focus on the detail of biblical texts. Though only one of the constituent features of CBS processes, textual detail not ordinarily accessible to “ordinary non-scholar readers” is a distinctive feature of CBS.7

Collaborative interpretation between scholar and non-scholar (or the trained reader and the ordinary reader of the Bible) has, like so much of South African reality, been marked by race and/as class. Biblical scholars have historically been, in the majority, white and middle-class.8 Ordinary readers of the Bible with whom we have worked over more than thirty years have historically been, in the majority, black, female, and working-class. CBS collaboration recognizes,9 but deconstructs – transgresses and transforms – the historically sectoral (scholar/non-scholar), class/racial (white/black), and gender (male/female) realities of biblical interpretation in South Africa.

Given the Bible’s ambiguous presence in African contexts, both a tool of imperialism and an African sacred icon,10 community-based CBS activism is a necessary postcolonial requirement of classroom-based biblical studies. A liberationist pedagogy requires community-based CBS-type work wherein the socially engaged biblical scholar is being regularly partially constituted by work with others.

Reading with and/as working with

Central to the work of the Ujamaa Centre, since its inception as the Institute for the Study of the Bible in 1989,11 has been notions taken from Sharon Welch’s “ethic of solidarity and difference”.12 Published at the same time as we were beginning our CBS work, aspects of Welch’s work shaped both our community-based and classroom-based work. Despite recognizing “the limitations in the work of postmodern social theory”,13 Welch leans heavily on Michel Foucault’s epistemology. Welch finds “in the thinking of Foucault compelling reasons for an epistemology of solidarity and a communicative ethic”.14

Welch, together with other feminists,15 is worried by Foucault’s “indifference” to who is speaking in a text at precisely the time when there is “an explosion of new speakers and writers”.16 “It is ironic”, she continues, “to find Foucault’s declaration of the death of the author and the self just as women and other marginalized people begin to write and assert their identity politically and culturally”.17 For this reason, she argues, “Some feminists have chosen, therefore, to work within the philosophical debate framed by Habermas over against that of Foucault, Derrida, or Lyotard”.18

But, despite such limitations, Welch finds value in postmodern social theory “for at least two reasons”. “First, we can find in the postmodern critique of Enlightenment reason and ‘grand narratives’ support for feminist critiques of unwarranted claims of universally valid interpretation of human experience and the nature of critical thinking”.19 Welch affirms here a similar argument made by Cornel West, whose work was formative in the emergence of the Ujamaa Centre.20 As West argues at length, postmodern points of view can serve “as a useful springboard for a more engaged, even subversive, philosophical perspective”. “This is so”, he continues, primarily because they encourage “the cultivation of critical attitudes toward all philosophical traditions, inducing a crucial shift in the subject matter of philosophers from the grounding of beliefs to the scrutiny of groundless traditions – from epistemology to ethics, truth to practices, foundations to consequences” and, in so doing, he argues, “such postmodern perspectives have the potential to lend themselves to emancipatory ends” in that they propose “the tenuous self-images and provisional vocabularies that undergird past and present social orders as central objects of criticism”. And, as West continues, such shifts are “particularly significant for those on the underside of history,” because “oppressed people have more at stake than others in focusing on the tenuous and provisional vocabularies which have had and do have hegemonic status in past and present societies”.21

Welch’s second reason for turning to postmodern social theory leads her and us to Foucault. As indicated, she finds “in the thinking of Foucault compelling reasons for an epistemology of solidarity and communicative ethic”.22 Her logic is instructive:

I concur with Habermas’s conclusion that there is an imperative to enter into dialogue with others, but for Foucault’s reasons. Habermas grounds dialogue and the search for consensus in the imperatives of the speech act itself. I find Foucault’s reasons for dialogue more compelling. Foucault argues that we can see a system of logic as a particular system and not as truth itself only when we are partially constituted by different systems of producing truth. We can transcend the blinders of our own social location, not through becoming objective, but by recognizing the differences by which we ourselves are constituted and, I would add to Foucault, by actively seeking to be partially constituted by work with different groups.23

Though led by black South African forms of liberation theology, we recognized resonances with Welch’s white feminist formulations.24 Welch’s notion of “actively seeking to be partially constituted by work with different groups” has been enacted and exegeted by us for over thirty years. Hence, we have forged CBS processes within which the Ujamaa Centre has actively sought to be partially constituted by work with organized sectors of the poor and marginalized.25 Welch’s underdeveloped notion of “work with” has been explicated as CBS praxis through the biblical hermeneutics of Latin American Liberation Theology, South African Black Theology, and South African Contextual Theology.26 Our understanding of “reading with” requires the prior reality of “working with”. The CBS work on 1 Kings 21 which is the focus of this article illustrates rather well how we understand the relationship between community-based activism, the Bible as a site of struggle, and classroom-based pedagogy.

Working with unemployed youth

The Ujamaa Centre has been working with the Sakhingomuso (“building the future”) youth group since 2014, collaborating with them over the past five years. During this period, the problem of youth (15–34 years old) unemployment in South Africa has worsened, standing officially at 38.2% in November 201827 when we did the workshop which included a CBS on 1 Kings 21.

As youth unemployment has increased over the five years of our collaboration, other youth group formations have joined the collaboration. Our engagement with these organized youth movements was to facilitate a conducive environment for critical deliberations on unemployment as a socio-economic challenge confronting South Africa. We have used the “Mzwandile Week” as the focal site for our work together. The week’s activities are in commemoration of our late colleague, Mzwandile R. Nunes, a life-long economic activist for forms of African socialism.

In 2015, the inaugural “Mzwandile R. Nunes Week” (now “Mzwandile Week”), was organized and facilitated by the Ujamaa Centre’s Bread Theology Programme, under the leadership of Sithembiso Zwane. For the 2015 Mzwandile Week the youth identified faith and the economy as fundamental areas for discussion, resulting in the theme, “Faith and Economic Justice: Youth as the Agents of Socio-Economic Transformation”. This theme engaged with the role of faith in ensuring that economic justice prevails. The 2016 Mzwandile Week focussed primarily on the building of social movements, including unemployed youth groups, HIV support groups, and Gender-Based Violence (GBV) survivor groups, contributing to our theme on “Revitalizing Social Movements for Socio-Economic Justice”. The emphasis in both 2015 and 2016 was to interrogate the dominant discourse that characterizes unemployed youth movements as “a lost generation”. Part of this narrative is a prevalent myth that unemployed youth are responsible not only for their own unemployment but also for criminal activities in local communities.

For the 2017 Mzwandile Week the youth decided on the issue of education as the focus. This was the beginning of the #FeesMustFall movement, which began within universities but which was taken up more broadly by a range of social movements and political formations.28 The youth re-visited the South African “Freedom Charter”, arguing that it promised that “the doors of learning … shall be opened”.29 The theme was “Education: Right or Privilege?” The deliberations centred on access to education for working-class youth previously deprived of the opportunities for quality education under the apartheid system.

In 2018, the youth argued that though the issue of education continued to be important, they felt strongly that they must reflect on the African National Congress’ (ANC) programme of “Radical Economic Transformation”,30 and the related proposed government bill on land expropriation without compensation.31 The youth in rural areas raised the issue of access to land as an economic justice issue. They argued vehemently that the land was central in addressing the economic challenges in South Africa. Furthermore, the youth from the rural areas under tribal authority raised concerns regarding the land under traditional-cultural leadership. Their concern was linked to gender dynamics in rural areas in particular, given that decisions about the allocation of land in rural areas is the prerogative of local chiefs and headmen. The socio-cultural patriarchal system has the propensity to undermine the role of women in decision-making processes, hence the concern about women’s access to land in the rural areas. Adding their urban voice to the discussion was Abahlali baseMjondolo, the shack-dwellers’ movement in South Africa,32 with whom the Ujamaa Centre has a long history of collaborative work. Urban land, under the control of the eThekwini Municipality in this case, regularly restricts access of the urban poor to urban land and evicts the urban poor from urban land they have occupied.

These combined rural and urban unemployed youth conceived the 2018 workshop, using the theme, “Gender, Land and Unemployment: Our Kairos Moment”. The participants came from youth formations in the districts of UMgungundlovu, Mbutshana, Dambuza, Umshwathi, as well as from the city of eThekwini. Approximately eighty unemployed youth participated in the workshop.

The different youth formations participated actively in the “See” moment of the See-Judge-Act process, analyzing the various social dimensions of the intersections between gender, land, and unemployment as a social reality of both the rural and urban poor. Having analyzed their social realities, they then called on the Ujamaa Centre to offer CBS resources as part of the “Judge” moment of the See-Judge-Act process. Key to both the “See” and “Judge” moments, and more specifically to their intersection (See-Judge), is our understanding of space. It is a particular conception of space that facilitates each of the moments and their intersection. CBS is a particular kind of space.

Inventing spaces

Space has long been a theoretical concept within the work of the Ujamaa Centre. Notions of indigenous African contestations of encroaching colonial space,33 the sequestered space in which a “hidden transcript” is nurtured on the margins of the public realm,34 the “circles of dignity” inhabited by marginalized subjects,35 the ambiguity of boundaries,36 and the heterotopic dimensions of space (and time),37 have informed and shaped our understanding of CBS occupying a safe and sacred space.38 As with any component of our conceptual apparatus that is CBS methodology, we continue to reflect on how we might understand the space within which we work.

The communities with whom we work have long been objects of various forms of “development”, whether colonial “development”, apartheid’s “separate development”, or even our liberation government’s neo-liberal capitalist co-opted “reconstruction and development”.39 Central to all of these forms of “development” is the desire to control the space (and time)40 of those considered African “objects”. Henri Lefebvre makes it clear in his analysis that, “(Social) space is a (social) product”.41 Significantly for our work with the unemployed, Lefebvre goes on to argue that the space “thus produced” by the global processes of commodities, money, and capital “also serves as a tool of thought and of action; that in addition to being a means of production it is also a means of control, and hence of domination, of power”.42 As a “reality of its own”,43 continues Lefebvre, “it escapes in part from those who would make use of it. The social and political (state) forces which engendered this space now seek, but fail, to master it completely”.44 Space, even controlled space, has taken on “a sort of uncontrollable autonomy”.45

Andrea Cornwall and her colleagues’ work on space has taken us further in the direction of the contestation of space. Cornwall sets up a contestation between “invited” (controlled) spaces and “popular” (liberated) spaces.46 Sithembiso Zwane has elaborated Cornwall’s conceptual analysis, arguing for a continuum from invited spaces to invigorated spaces to invented spaces. Not only is this elaboration useful in its own right, but it maps rather nicely on to another continuum we work with: the continuum of interpretive resilience, interpretive reworking, and interpretive resistance.47 Zwane, following Cornwall, recognizes that invited spaces undermine progressive forces and adversely entrench an economic and political hegemony that dehumanizes and undermines people’s agency and praxis. Invited spaces, characterized by exclusion or at best supervised participation, deprive the community of the ability to participate in development processes. Invigorated spaces, in which local community sectors are partially in control, contend with invited spaces and may lead to the formation of invented spaces, within which local community sectors are substantially in control.

CBS space is a form of invigorated space. Invigorated spaces provide much needed capacity to unemployed youth to challenge their non-participation and exclusion from development processes. The focus of invigorated spaces is capacity-building for those excluded or marginalized by neo-liberal development processes. Invigorated spaces contribute to the building of agency within the religious and social movements, enabling them to challenge marginalization and exclusion. The invigorated spaces of agency created by the collaborative work of the Ujamaa Centre contend with invited spaces. Furthermore, invigorated spaces facilitate the creation of the invented spaces within which interpretive resistance might flourish, and that have the potential to lead to participatory community development. Cornwall argues that the “popular” or “invented” spaces are those “arenas in which people come together at their own instigation”;48 “arenas within and from which people are able to frame alternatives, mobilise, build arguments and alliances and gain the confidence to use their voice, and to act”.49

In-between invited and invented spaces, we argue, are the invigorated spaces of resilience that find expression in the redemptive religious pedagogy of CBS. Invigorated spaces facilitate the creation of invented spaces, and within such spaces the potential for interpretive resistance. The unemployed and working-class disrupt invited spaces, but also make use of the kinds of invigorated space available to them, such as the collaborative space of the Ujamaa Centre’s CBS processes. The organized unemployed and working-class inhabit this invigorated space and from within it forge invented spaces in which to engage in collective action, mobilizing other social agents to challenge social, economic, and political injustices in the public realm. These spaces are critical in re-defining community engagement from below, and among these spaces is the space constructed by CBS.

In contexts in which religion is a significant feature of life, such as in South African contexts, there can be no sustained social change without religious change.50 Dominant forms of religion mitigate against change “from below”, having formed alliances with political elites.51 Even in post-liberation South Africa, political elites and religious elites publically advocate for privatized forms of what the Kairos Document referred to as “church theology”.52 Doing development “from below”,53 with the unemployed youth as agents of their own economic transformation, requires theological transformation. Theological transformation is the praxis CBS offers in our collaborative work.

CBS is our particular contribution to theological change. In the next section we reflect on the formation of the 1 Kings 21 CBS.

Discerning biblical detail

First Kings 21, The Story of Naboth’s Vineyard, as it is popularly known in African contexts and beyond, is a regular resource for African postcolonial biblical scholarship.54 The Ujamaa Centre’s CBS work on this text both draws on and contributes to this trajectory. In 2003 we were invited by a local Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO), the Church Land Programme, to work with them and a local Community-Based Organisation (CBO), the Rural Network, on a CBS series on land issues.55 The “See” process in 2003 identified five key issues: land possession and land dispossession, women and land, food security and land, leadership and land, and HIV and AIDS and land. Together we constructed a CBS with which to engage each of these dimensions of the land struggle, using 1 Kings 21 as the basis for the CBS on land possession and land dispossession. At the time we did not consider this biblical text as a resource for gender and land (choosing instead Numbers 27:1-11, the account of the petition by the daughters of Zelophehad and the law concerning inheritance of land in the event of a man having daughters and no sons).56

In 2003 our CBS on 1 Kings 21 took the following form, offering two related versions, depending on the specific context:57

1. What is this text about?

2. Who are the characters and what do we know about them?

3. Why does Ahab want Naboth’s vineyard?

4. Why does Naboth want to keep his vineyard?

5. What strategies are used to take Naboth’s vineyard from him?

6. What role do race and class and ethnicity play in this story?

7. Why and how have people in your community lost their land?

8. Why is this land your land?

9. What strategies are there to regain your land?

10. What will be your plan of action?

[Or, if the community is struggling to retain its land:]

7. Why is this land your land?

8. What strategies are being used to take away your land?

9. What resources are there for you to retain your land?

10. What will be your plan of action?

When the invitation came from the “Gender, Land and Unemployment: Our Kairos Moment” workshop described above, we decided to revisit the 1 Kings 21 biblical text, having recognized its potential for intersecting gender and class and land. Because biblical studies generates potentially useful textual detail for the construction of CBS, we trawl “biblical studies” for such (subversive)58 detail. In the case of 1 Kings 21 the work of South African Makhosazana Nzimande provided additional detail for our ongoing CBS work on this biblical text. We first came across Nzimande’s work on this text in her (US-based) doctoral dissertation (2005),59 and Gerald West invited her to write a summary version of her argument as an essay for a collection on African biblical interpretation so that it would be more readily available to a wider African audience.60 In constructing our earlier version of the 1 Kings 21 CBS, working with the Church Land Programme and the Rural Network in 2003, Nzimande’s work was not yet available. But we were familiar with our colleague Elelwani Farisani’s emerging work.61 In different ways in the early days of the Ujamaa Centre (then known as the Institute for the Study of the Bible) we grappled with how to make use of potentially useful biblical studies detail, including work that was being done by biblical studies students like Farisani.

What Nzimande’s work on 1 Kings 21 offered us, when we returned to 1 Kings 21 more than a decade later in order to construct a CBS with another local community, was an overtly inter/trans-sectoral hermeneutic. Though “intersectionality” has made a significant conceptual contribution within biblical studies,62 we prefer the more Marxist notion of “sectoral”, indicating as it does the fundamental presence of the economic and an implied ideological commitment to marginalized economic sectors. Among the many inter-sectoral features of South African reality, race and/as class, gender, and land were the focus of this CBS, and Nzimande’s analysis offered us plenty of potential biblical and contextual detail to work with.

Nzimande uses the metaphor of imbokodo (the grinding stone),63 an item of rural African women’s work, in order overtly to intersect/transect race, class, gender, and culture. She draws deeply on the trajectories of the three overlapping phases of South African Black Theology within which she stands, and inaugurates a fourth phase in which class is a distinctive feature not only within an analysis of the apartheid system but also of “traditional” indigenous African culture and community.64 Like Itumeleng Mosala,65 whose class-laden analysis she takes up, Nzimande sets out to establish lines of connection between the economic systems of contemporary struggles and the economic struggles of “the oppressed and exploited in the text”.66 In so doing she also takes up Mosala’s challenge of understanding what is required hermeneutically to use the Bible to get the land back.67

Nzimande’s contribution to the post-apartheid land restitution project is to bring her South African context into dialogue with kindred struggles “over stolen lands” in the biblical text.68 Her first interpretive move follows Mosala, using historical-critical resources to locate the biblical text (1 Kings 21:1-16) historically. But her next move is not a Mosala-like Marxist materialist sociological analysis of this period; instead, she draws on feminist literary analysis in order to provide a detailed characterisation of the leading female character (queen Jezebel). The Mosala-like sociological contribution, but using postcolonial theory, comes in her next move, where she locates the text within its imperial setting (Phoenician imperialism), giving attention to both the literary-narrative imperial setting and the socio-historical imperial setting of the biblical text. She then takes up Mosala’s specifically economic emphasis in her final textual interpretive move, which is to delineate the class relations within this imperial context (including Jezebel as part of a royal household).69

She then brings this text and her set of (imbokodo) inter/trans-sectoral interpretive resources into dialogue with an inter/trans-sectoral analysis of the South African context, recovering the identity and agency of African queen-mothers in their governance of African land. The postcolonial recovery of African culture and/as religion as envisaged by South African Black Theology is apparent here. But, in an innovative move, she does not conclude her work with this religio-cultural recovery. She pushes the boundaries of (African) feminist postcolonial criticism to include matters of class, recovering the “voices” of “those at the receiving end of the Queens’ and Queen Mothers’ policies”.70 She uses her imbokodo hermeneutics “to read with sensitivity towards the marginalised and dispossessed”,71 the South African equivalents of Naboth’s wife,72 recognizing that “the beneficiaries” of indigenous elites, including indigenous queens and queen mothers, “are themselves and their sons, rather than the general grassroots populace they are expected to represent by virtue of their royal privileges”.73

Summoned by a local community struggle, shaped by the realities of unemployed South African youth, and resourced by Nzimande’s inter/trans-sectoral work on 1 Kings 21, we constructed and facilitated the following CBS:

1. Listen to a dramatic reading of 1 Kings 21:1-16. What is this text about?

2. Who are the characters in this story and what do we know about them? Draw a picture of their relationships.

3. What are the strategies and systems that those in power (Ahab and Jezebel) use to take Naboth’s land?

4. What indications does the story give about why there is no solidarity between Jezebel and Naboth’s wife as women?

5. What strategies are used by the powerful in South Africa (both in the private and public sector) to control land and other economic resources?

6. Read 1 Kings 21:17-20. How does God respond to this injustice? How does the prophet Elijah respond to this injustice?

7. How should the churches respond? How should the churches collaborate with the unemployed and landless? What actions can we take to challenge the churches to work in solidarity with the unemployed and landless?

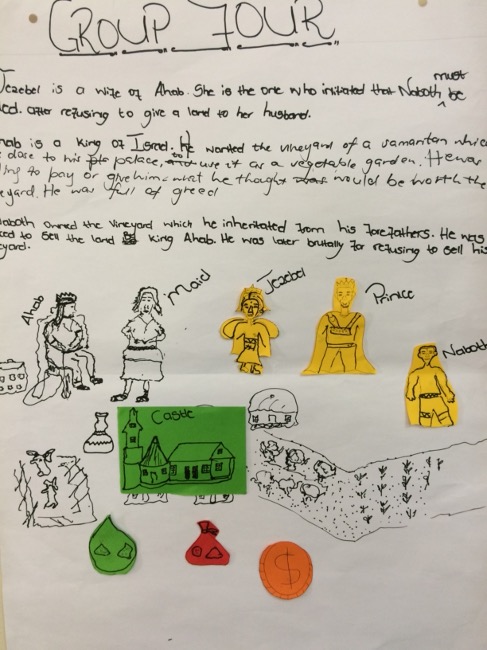

The participants devoted more than seven hours to this CBS, refusing to conclude the process until they felt it was complete. The pictures each small group had drawn (Question 2) were referred to (and amended) again and again as they continued the process, offering a cumulative account of each small group’s discussions. One of the small groups made innovative use of movable cut-out figures and objects, enabling them to show how people and resources transacted and so participated in exploitation (see picture).

As Questions 2, 3, and 4 demonstrate, we prioritize literary-narrative questions, recognizing that such questions provide an egalitarian, but still “critical” in the biblical studies sense, entry into the detail of a biblical text.74 The literary-narrative character-driven analysis of Question 2 was crucial to the CBS. Question 2 required careful and regular re-readings as each small-group of about 7-9 participants used the question to analyze character, plot, and setting. Setting, both temporal and spatial, is a distinctive feature of the narrative, which is why we invited participants to draw a picture. Considerable time was spent on this task, resulting in a close reading of the narrative detail.

The dominant theological orientation in much of contemporary (African) Christianity is towards the individual and the moral, what the South African Kairos Document refers to as “church theology”.75 The young people we collaborated with are heirs of church theology accounts of unemployment, where being unemployed is considered the result of personal moral failings.76 Question 3 probed, therefore, the systemic dimensions of land expropriation. This story is about more than “good” and “bad” individuals; it is about, Question 3 suggests, systems of exploitation. Systemic analysis was central to the 1980s struggle against apartheid, but a decline in post-liberation South Africa of what the Kairos Document refers to as “prophetic theology” has meant that systemic analysis has almost disappeared from theological discourse.77 So there was a palpable excitement in the room as the small groups grappled with Question 3, recognizing not only exploitative systems within the text but emerging resonances with exploitative systems in their own contexts.

However, the contours of the CBS remained within the biblical text for one more question, Question 4. This question facilitates reflection on inter-sectoral engagements between class and gender systems. We decided not to foreground the ethnic dimensions of the story in our CBS questions, focussing instead on class. We worried, particularly given the realities of xenophobia in South Africa, that ethnic matters might deflect from the class concerns that were part of the summons from this sector of unemployed youth. Interestingly, some of the participants did engage with the ethnic identity of Jezebel, but with an emphasis on how her ethnic privilege was used to exploit other women. Equally interesting was how those participants who read back into the story of Jezebel (earlier in 1 Kings), in order to answer Question 2 (though this is not an intended task of Question 2), did not place any emphasis on her different religious background. What interested them was how her particular ethnic identity included education. Her ethnic background clearly allowed her, as the daughter of a king, to have access to education, for she was able to send letters in her husband Ahab’s name (v. 8). Yet, the participants were disappointed to note, she did not use her education to empower her sister, Naboth’s wife. She used her education to participate in hetero-patriarchal systems, perpetuating econo-patriarchy.78

Though we privilege literary-narrative questions in CBS work, because of their capacity to be inclusive of “ordinary” reader-hearers of the Bible, such questions often generate specific socio-historical questions. We were prepared, therefore, with the kind of socio-historical resources Nzimande uses in her imbokodo interpretation, and we shared these resources with participants when asked about the ancient systems that produced a text like this.

Question 5 moves the CBS from a repeatedly re-read text into the lived context of the participants. With the additional biblical and theological resources offered by the previous questions, Question 5 gave opportunity to each small-group to do inter-sectoral systemic analysis of their own realities. A major theological shift could be felt among participants as they began to articulate a more systemic-prophetic theological understanding of their contexts. They were unemployed not because of personal factors but because of systemic factors. Understanding and owning this recognition moves the CBS from “Judge” to “Act” (Question 7).

But before we moved organically to the “Act” moment of CBS we disrupted the typical flow of a CBS by offering another text-related question, Question 6.

The redactional processes by which the Bible has been produced are important to our CBS work. We are persuaded by Itumeleng Mosala that “the texts of the Bible are sites of struggle”.79 Though Mosala acknowledges that the final literary form of the biblical text bears witness to these struggles,80 his primary focus is the socio-economic sites of struggle that produced and are evident within the various redactional editions of the biblical text. While Mosala accepts the final form as a starting point for ideological redaction-critical work, he recognizes that the final form “cannot provide inspiration to oppressed peoples because it is inherently a theology of domination and control”.81 So, for Mosala, ideology-driven redactional work is a necessity if we are to appropriate the Bible for liberation. The enduring problem, according to Mosala, is that the final form of the Bible we have and use is a form shaped by the dominant classes of particular historical periods in the Bible’s formation. Dominant classes have through the redactional processes of the Bible’s composition co-opted the ideological perspectives of other socio-economic sectors. Collaborative work between socially-engaged biblical scholars and ordinary readers from within the struggles of the poor and marginalized is therefore required in order to “discover kin struggles in biblical communities”, for it is only then that there is the potential for “[t]hese biblical struggles … [to] serve as a source of inspiration for [their] contemporary struggles, and as a warning against their co-optation”.82

Even biblical prophets “co-opt” the voices of the most marginalized.83 So it was with some caution that we offered Question 6 in the 1 Kings 21 CBS. The question proved to be enabling, offering additional textual resources for moving into forms of community-based action (Question 7). But, we wonder, is the prophetic voice required in order to hear the voices of Naboth, his wife, and children crying out against injustice? Perhaps, but Mosala reminds us that often a contemporary struggle “draws its poetry from a future that in this struggle’s collision with … [much of the biblical text as we have it] is experienced as an ‘absence’”.84 In the language of the Kairos Document, “people’s theology” may be as much a resource within the biblical text as it is in the construction of contemporary forms of “prophetic theology”. The Revised Second Edition (1986) of the Kairos Document makes an important distinction between “people’s theology” and “prophetic theology”:

It should also be noted that there is a subtle difference between prophetic theology and people’s theology. The Kairos Document itself, signed by theologians, ministers and other church workers, and addressed to all who bear the name Christian is a prophetic statement. But the process that led to the production of the document, the process of theological reflection and action in groups, the involvement of many different people in doing theology was an exercise in people’s theology. The document is therefore pointing out two things: that our present Kairos challenges Church leaders and other Christians to speak out prophetically and that our present Kairos is challenging all of us to do theology together reflecting upon our experiences in working for justice and peace in South Africa and thereby developing a better theological understanding of our Kairos. The method that was used to produce the Kairos Document shows that theology is not the preserve of professional theologians, ministers and priests. Ordinary Christians can participate in theological reflection and should be encouraged to do so. When this people’s theology is proclaimed to others to challenge and inspire them, it takes on the character of a prophetic theology.85

There can be no “prophetic theology” without there first being a “people’s theology”, according to the Kairos Document. This is indeed the starting point of the Ujamaa Centre’s work. We begin with the lived reality of local communities of the poor and marginalized as it is embodied by them. This is the “raw material” of prophetic theology. And CBS is a process, given invigorated time and space, that enables this people’s theology to become prophetic theology.86 What Mosala’s ideological redactional work suggests is that we find something similar within the biblical text, “beneath” the redactional layers of dominant-class voices.87 Even without Question 6 the participants were attentive to the absent voices of Naboth’s family. What Question 6 offered was an overt prophetic voice – though this prophetic voice then goes on to co-opt the economic dimensions of the story for theological purposes (v. 26).

The focus in 1 Kings 21, participants argued, is on the activation of patriarchal power networks for economic exploitation. Econo-patriarchy rules. Participants, through their discussion of Question 4, were disturbed by the lack of solidarity between Jezebel and Naboth’s wife. Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo (“You strike a woman, you strike a grinding stone”) is a familiar refrain, echoing though “African time”88 since the 9th August 1956, when over 20,000 South African women of different races and/as classes marched to the Union Buildings, singing this resistance song,89 to protest the apartheid “pass” laws, under which “non-Europeans” were compelled to carry “passes”.90 Where was a similar show of solidarity among these biblical sisters in 1 Kings 21, the CBS participants wondered? What shocked participants was not only that Jezebel had exploited her sister, but how she had carefully employed patriarchal power (vv 8-10), writing letters “in Ahab’s name” and sealing them “with his seal” and sending them to his fraternal networks of other powerful men (v. 8). Instead of using her educational privilege (as one of the Phoenician elite) in solidarity with other women, Jezebel chose to use her education to exploit economically her sister, Naboth’s wife. Class interests ruled. Participants were also appalled by the content of the letters, in which Jezebel in her guise as patriarch “captured”91 the religious and legal systems of ancient Israel for her own family’s economic gain (vv 9-10). The econo-patriarchy of “the men of his city” (v. 11) was deployed by a woman.

These considerable participant-generated re-reading resources were used to mobilize and commit these formations of unemployed youth to further action. Each small group offered its own specific “action plan,” whether focussed on the church (as Question 7 suggests) or more widely on other institutional systems, including local, provincial, and national government.

We, the Ujamaa Centre, for our part, continue with our work, moving back-and-forth between community and academy.

Re-inventing classroom space

Returning to classroom space, we shared our CBS work on 1 Kings 21 with students, both third-level undergraduate students and postgraduate students. Much of the pedagogy of what is now the School of Religion, Philosophy, and Classics at the University of KwaZulu-Natal has been formulated through careful and rigorous intentional context-directed debate within the School.92 The Ujamaa Centre’s contribution to this debate, drawing on collegial strands of already present reflection, and specific contributions from feminist pedagogy,93 was to envisage “contextual” pedagogy as a threefold cord/chord braiding the embodied “engagement” with the Bible that students bring to the discipline in their biblical studies modules, with the “critical distance” that biblical studies methods construct in the reading of the biblical text, through forms of “contextuality” like CBS.94 “Contextuality”, we argued, enabled students to recognize the capacity of biblical studies critical detail (generated by biblical studies critical methods) as a resource for community-based (systemic) social change. Contextuality enabled biblical engagement and biblical critical distance to forge emancipatory alliances.

The biblical studies curriculum reflects this pedagogical orientation. Instead of beginning the first year of biblical studies with an introduction to the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible (and Hebrew), we begin with an introduction to the New Testament (and Greek) because we recognize that the vast majority of our students come from a New Testament oriented Christian experience. Then, in the first module of the second year of biblical studies (“Text, Interpretation, and Culture”), we demonstrate that each constituent of the major biblical studies cluster of methods, literary-narrative and socio-historical methods, for instance, offers critical detail that may be useful for CBS-type work in local churches and communities. The second-semester module in the second year (“Critical Tools for Biblical Study”) deepens the students’ critical capacities with a careful focus on literary-narrative critical methods and socio-historical critical methods. These capacities are then appropriated in the capstone exit module in the third year (“Biblical Theology”), where we foreground contextual realities, using various African realities to summon particular critical detail from particular biblical texts, using both literary-narrative and socio-historical methods. Literary-narrative methods almost always precede the use of socio-historical methods, precisely because literary-narrative methods are closer to (through different from) the students’ “ordinary” ecclesial and devotional interpretive “methods”. Embodied engagement with the Bible is our starting point, taking seriously the “cultural capital” students bring with them to academic biblical studies.

In the compulsory third year module (“Biblical Theology”) and our postgraduate core module (“Biblical Interpretation”) we work overtly with the notion of the Bible as “a site of struggle”. Shaped by, but going beyond the biblical hermeneutics of the Kairos Document,95 we appropriate Mosala’s notion of the Bible as “a site of struggle”.96 Mosala reminds us that biblical studies has always been aware of “the tendency in biblical literature for older traditions to be reused to address the needs of new situations”.97 What Mosala adds to this understanding is the ideological nature of the such reuse. Redactional activity is not ideologically innocent.98

Among the contemporary contextual realities that constitute the third-year biblical theology module, the postgraduate biblical interpretation core module, and the elective biblical studies modules in the second semester of our postgraduate programme is an emphasis on economics and gender and land, and on their intersections. In 2019, within both the third-year biblical theology module and the elective biblical studies module “Issues of Gender and Masculinity”, we used Nzimande’s essay and our CBS work within a biblical studies pedagogical context. Community-based CBS work “does” contextual critical Bible re-reading. Classroom-based pedagogy reflects on the relationship between biblical exegesis (to claim an old-fashioned notion) and CBS praxis. Students interrogate how particular biblical studies detail is discerned using biblical studies method, how accountability to particular community-based realities risks a partial appropriation of this detail, and how this detail is given shape by CBS methodology.

While analyzing our most recent version of the 1 Kings 21 CBS with the postgraduate class, one of the Master’s students, who had engaged with 1 Kings 21 in both the core biblical studies module and the elective module, decided to use this CBS as part of his thesis research. He wanted to probe the absence of Naboth’s family more fully; and so we began to reflect on how we might adapt the CBS yet again. Many years ago we had done something similar in constructing a CBS on 2 Kings 5, the story of Naaman the leper, reading it as the story of the unnamed slave girl who is pivotal to the plot. This CBS worked rather well, with participants having no problem at all in focussing on a story that the biblical text implies but does not tell.99 One of our Master’s students at that time used the 2 Kings 5 CBS as part of her thesis research.100 Indeed, CBS work not only reshapes biblical studies’ pedagogy, it reshapes the discipline of biblical studies itself and academic research more generally. While CBS is first and foremost a form of emancipatory praxis, inhabiting invigorated and invented spaces, it can be used, with care, as a form of participatory research.101

During 2019, while we were reflecting on the 1 Kings 21 CBS work with unemployed youth, and while one of our Master’s students was considering how he might use a revised version to focus on the absent but narratively implied presences of Naboth’s family, the Ujamaa Centre was invited by the organization Anglican Alliance to collaborate with them in creating a set of CBS on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Among the CBS ideas our collaborative working group contemplated was one that intersected land, power, and gender. We offered the following revised version of 1 Kings 21 that we had been working on. Though it has not yet been used in this form, the revised 1 Kings 21 CBS, in which Naboth’s family is a focus, takes the following shape:

1. Listen to a dramatic reading of 1 Kings 21:1-16. What is this text about?

2. Who are the characters in this story and what do we know about them? Draw a picture of their relationships.

3. What are the strategies and systems used by those in power (Ahab and Jezebel) to take Naboth’s land?

4. What indications does the story give about why there is no solidarity between Jezebel and Naboth’s wife as women?

5. Are there women like Naboth’s wife in your communities? What are their names and why have they lost their land?

6. What strategies are used by the powerful in your contexts to control land and other economic resources?

7. Read 1 Kings 21:17-20. How does God respond to this injustice? How does the prophet Elijah respond to this injustice?

8. How should the churches respond prophetically? How should the churches collaborate with the unemployed and landless? What actions can we take to challenge the churches to work in solidarity with the unemployed and landless?

This version is very similar to the CBS discussed more fully above, which we did with the unemployed youth. What is distinctive about this revised version is Question 5, where we invite participants to “complete” the story. As Musa Dube argues, African Semoya readers re-write the imperial Bible as an inclusive Bible, using participatory and communal genres in the African struggle for survival, healing, resistance, and empowerment.102 “[T]he biblical story is an unfinished story: it invites its own continuation in history”.103 Decolonization, says Dube, “calls for a practice of reading, imagining, and retelling biblical stories in negotiation with other religious stories in the post-colonial era”.104 Question 5 invites such re-tellings.

Conclusion

CBS plays a role in invigorating, and perhaps even inventing, community-based space. And the CBS work done within community-based spaces offers significant capacity, as indicated, for reconfiguring, even reinventing, classroom-based space. This is intentional, for when the Ujamaa Centre was being forged in the late 1980s, the initial proposal was to establish it as an NGO among the many other Faith-Based Organisations (FBOs) of that period. But Gunther Wittenberg, the founder of the Institute for the Study of the Bible (ISB), the Ujamaa Centre’s earlier incarnation, was persuaded by his colleagues in the (then) School of Theological Studies in the (then) University of Natal to locate the ISB within the School, so that it might partially reconstitute theological education.105 This the work of the ISB-Ujamaa Centre has done, contributing towards what Julia Preece (a colleague in adult education we have worked with) refers to as “the porous university”.106 1 Kings 21 has moved back-and-forth between community and academy, partially transforming both, summoning the academy to serve community-based activism and enabling the community to re-invent the classroom.

Works Cited

Abahlali baseMjondolo. Available online: http://abahlali.org/ (accessed 28 December 2019).

Ali, Diana. “Safe Spaces and Brave Spaces. Historical Context and Recommendations for Student Affairs Professionals.” NASPA Policy and Practice Series 2 (2017): 1–13.

ANC. “Economic Transformation: ANC Discussion Document 2017.” Available online: https://www.politicsweb.co.za/documents/economic-transformation-anc-discussion-document-20 (accessed 28 December 2019).

Banerjee, Abhijit, Sebastian Galiani, Jim Levinsohn, Zoe McLaren, and Ingrid Woolard. “Why Has Unemployment Risen in the New South Africa?”. Economics of Transition 16/4 (2008): 715–40.

Benhabib, Seyla and Drucilla Cornell. Feminism as Critique: On the Politics of Gender. Feminist Perspectives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Beukes, Rosemary. “A Re-Reading of 2 Kings 5: In Search of a Redemptive Masculinity.” Master’s dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2014.

Booysen, Susan. Fees Must Fall: Student Revolt, Decolonisation and Governance in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2016.

Cochrane, James R. Circles of Dignity: Community Wisdom and Theological Reflection. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1999.

Cochrane, James R. and Jonathan A. Draper. “The Parting of the Ways: Reply to John Suggit.” Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 59 (1987): 66–72.

Comaroff, Jean. and John L. Comaroff. Of Revelation and Revolution: Christianity, Colonialism and Consciousness in South Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Comaroff, John L. and Jean Comaroff. Of Revelation and Revolution: The Dialectics of Modernity on a South African Frontier. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Cornwall, Andrea. “Introduction: New Democratic Spaces? The Politics and Dynamics of Institutionalised Participation.” IDS Bulletin 35/2 (2004): 1–10.

Cornwall, Andrea and Vera Schatten P. Coelho. Spaces for Change? The Politics of Citizen Participation in New Democratic Arenas. London: Zed Books, 2007.

Diamond, Irene and Lee Quinby, eds. Feminism & Foucault: Reflections on Resistance. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988.

Draper, Jonathan A. “Old Scores and New Notes: Where and What Is Contextual Exegesis in the New South Africa?” Pages 148–68 in Towards an Agenda for Contextual Theology: Essays in Honour of Albert Nolan. Edited by McGlory T. Speckman and Larry T. Kaufmann. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2001.

Dube, Musa W. “Readings of Semoya: Batswana Women’s Interpretations of Matt. 15:21-28.” Semeia 73 (1996): 111–29.

Dube, Musa W. “Toward a Postcolonial Feminist Interpretation of the Bible.” Semeia 78 (1997): 11–26.

Explore Heterotopia. Available online: http://foucault.info/documents/heteroTopia/foucault.heteroTopia.en.html (accessed 28 December 2019).

Farisani, Elelwani Bethuel. “Land in the Old Testament: The Conflict between Ahab and Elijah (I Kings 21:1-29), and Its Significance for Our South African Context Today.” Master’s dissertation, University of Natal, 1993.

Farisani, Elelwani and Dorothy Farisani. “The Abuse of the Administration of Justice in 1 Kings 21:1-29 and Its Significance for Our South African Context.” Old Testament Essays 17/3 (2004): 389–403.

Fiorenza, Elisabeth Schüssler. “Between Movement and Academy: Feminist Biblical Studies in the Twentieth Century.” Pages 1–17 in Feminist Biblical Studies in the Twentieth Century: Scholarship and Movement. Edited by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2014.

“The Freedom Charter.” Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand, 1955.

Gifford, Paul. African Christianity: Its Public Role. London: Hurst & Company, 1998.

Gora, Kennedy. “Postcolonial Readings of 1 Kings 21:1-29 Within the Context of the Struggle for Land in Zimbabwe: From Colonialism to Liberalism to Liberation, to the Present.” Master’s dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2008.

Government. 21 December 2018. “Draft Expropriation Bill, 2019.” No. 42127. Department of Public Works. Government Gazette. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201812/42127gon1409s.pdf (accessed 28 December 2019).

Gwala, Sibusiso. “The Impact of Unemployment on the Youth of Pietermaritzburg.” MTh dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2007.

Habib, Adam. Rebels and Rage: Reflecting on #Feesmustfall. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2019.

Heffernan, Anne, Noor Nieftagodien, Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, Bhekizizwe Peterson, Ian M. Macqueen, Arianna Lissoni, Sibongile Mkhabela, Steve Mokwena, Saleem Badat, Sekibakiba Peter Lekgoathi, Makhosazana Xaba, Tshepo Moloi, Franziska Rueedi, Premesh Lalu, Phindile Kunene, Brad Brockman, and Leigh-Ann Naidoo. Students Must Rise: Youth Struggle in South Africa before and Beyond Soweto ’76. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2016.

“The Judicial Commission of Inquiry Into Allegations of State Capture.” Available online: https://www.sastatecapture.org.za/ (accessed 28 December 2019).

Kairos, Challenge to the Church: The Kairos Document: A Theological Comment on the Political Crisis in South Africa. Braamfontein: The Kairos Theologians, 1985.

Kairos, The Kairos Document: Challenge to the Church: A Theological Comment on the Political Crisis in South Africa. Revised Second Edition. Braamfontein: Skotaville, 1986.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1991.

Maluleke, Tinyiko S. and Sarojini Nadar. “Alien Fraudsters in the White Academy: Agency in Gendered Colour.” Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 120 (2004): 5–17.

Masenya, Madipoane and Hulisani Ramantswana. “Anything New under the Sun of South African Old Testament Scholarship? African Qoheleths’ Review of OTE 1994-2010.” Old Testament Essays 25 (2012): 598–637.

Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Mosala, Itumeleng J. Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology in South Africa. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989.

Mtshiselwa, Ndikho. “A Re–Reading of 1 Kings 21:1–29 and Jehu’s Revolution in Dialogue with Farisani and Nzimande: Negotiating Socio–Economic Redress in South Africa.” Old Testament Essays 27/1 (2014): 205–30.

Nadar, Sarojini and Isabel A. Phiri. “Editorial.” Journal of Constructive Theology 14 and15 (2008/2009): 1–8.

Ndlovu, Musawenkosi W. #Feesmustfall and Youth Mobilisation in South Africa: Reform or Revolution? Routledge Contemporary South Africa. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

Nzimande, Makhosazana K. “Postcolonial Biblical Interpretation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: The Gebirah in the Hebrew Bible in the Light of Queen Jezebel and the Queen Mother of Lemuel.” PhD dissertation, Texas Christian University, 2005.

Nzimande, Makhosazana K. “Reconfiguring Jezebel: A Postcolonial Imbokodo Reading of the Story of Naboth’s Vineyard (1 Kings 21:1-16).” Pages 223–58 in African and European Readers of the Bible in Dialogue: In Quest of a Shared Meaning. Edited by Hans de Wit and Gerald O. West. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

Okure, Teresa. “Feminist Interpretation in Africa.” Pages 76–85 in Searching the Scriptures: A Feminist Introduction. Edited by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza. New York: Crossroads, 1993.

“Pass laws in South Africa 1800–1994.” South African History Online. Available online: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/pass-laws-south-africa-1800-1994 (accessed 28 December 2019).

Preece, Julia. University Community Engagement and Lifelong Learning: The Porous University. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Rabinow, Paul, ed. The Foucault Reader. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984.

“SA has highest youth unemployment rate in the world.” The Citizen. Available online: https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/2025384/sa-has-highest-youth-unemployment-in-the-world/ (accessed 28 December 2019).

Scheffler, Eben. “Royal Care for the Poor in Israel’s First History: The Royal Law Deuteronomian 17:14-20), Hannah’s Song (1 Samuel 2:1-10), Samuel’s Warning (1 Samuel 8:10-18), David’s Attitude (2 Samuel 24:10-24) and Ahab and Naboth (1 Kings 21) in Intertext.” Scriptura 116 (2017): 160–74.

Schreiter, Robert J. Constructing Local Theologies. Maryknoll: Orbis, 1985.

Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1990.

“Study 1: Land Dispossession.” Churchland. Available online: http://www.churchland.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/BibleStudy1.pdf (accessed 28 December 2019).

“Study 2: Women and Land.” Churchland. Available online: http://www.churchland.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/BibleStudy2.pdf (accessed 28 December 2019).

Terreblanche, Sampie. A History of Inequality in South Africa, 1652-2002. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 2002.

Tshehla, Maarman S. “Africa, Where Art Thou? Pondering Post-Apartheid South African New Testament Scholarship.” Neotestamentica 48/2 (2014): 259–81.

Ujamaa Centre. Available online: http://ujamaa.ukzn.ac.za/Homepage.aspx (accessed 28 December 2019).

Vaage, Leif E., ed. Subversive Scriptures: Revolutionary Readings of the Christian Bible in Latin America. Valley Forge: Trinity Press International, 1997.

Vengeyi, Obvious. “Land as an Inalienable Asset: Lessons from 1 Kings 21:1-29.” Pages 59–82 in Land: An Empowerment Asset for Africa: The Human Factor Perspective. Edited by Claude G. Mararike. Harare: University of Zimbabwe, 2014.

Weiler, Kathleen. “Freire and a Feminist Pedagogy of Difference.” Harvard Educational Review 61 (1991): 449–74.

Welch, Sharon D. A Feminist Ethic of Risk. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1990.

West, Cornel. “Afterword: The Politics of American Neo-Pragmatism.” Pages 259–75 in Post-Analytic Philosophy. Edited by J. Rajchman and Cornel West. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

West, Gerald O. Biblical Hermeneutics of Liberation: Modes of Reading the Bible in the South African Context. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 1991.

West, Gerald O. “No Integrity Without Contextuality: The Presence of Particularity in Biblical Hermeneutics and Pedagogy.” Scriptura S11 (1993): 131–46.

West, Gerald O. Biblical Hermeneutics of Liberation: Modes of Reading the Bible in the South African Context. Second Revised edn. Maryknoll: Orbis Books and Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 1995.

West, Gerald O. “Power and Pedagogy in a South African Context: A Case Study in Biblical Studies.” Academic Development 2/1 (1996): 47–65.

West, Gerald O. “Reading Abused Female Bodies in the Bible: Interpretative Strategies for Recognising and Recovering the Stories of Women Inscribed by Violence but Circumscribed by Patriarchal Text (2 Kings 5).” Old Testament Essays 15 (2002): 240–58.

West, Gerald O. The Academy of the Poor: Towards a Dialogical Reading of the Bible. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2003.

West, Gerald O. “Beyond the ‘Critical’ Curtain: Community-Based Service Learning in an African Context.” Teaching Theology and Religion 7/2 (2004): 71–82.

West, Gerald O. “Newsprint Theology: Bible in the Context of HIV and AIDS.” Pages 16–86 in Out of Place: Doing Theology on the Crosscultural Brink. Edited by Jione Havea and Clive Pearson. London: Equinox Publishing, 2011.

West, Gerald O. “Deploying the Literary Detail of a Biblical Text (2 Samuel 13:1-22) in Search of Redemptive Masculinities.” Pages 297–312 in Interested Readers: Essays on the Hebrew Bible in Honor of David J.A. Clines. Edited by James K. Aitken, Jeremy M. S. Clines, and Christl M. Maier. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013.

West, Gerald O. “The School of Religion, Philosophy, and Classics: Doing Contextual Theology in Africa in the University of Kwazulu-Natal.” Pages 919–26 in Handbook of Theological Education in Africa. Edited by Isabel Apawo Phiri and Dietrich Werner. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2013.

West, Gerald O. “The Biblical Text as a Heterotopic Intercultural Site: In Search of Redemptive Masculinities.” Pages 241–57 in Bible and Transformation: The Promise of Intercultural Bible Reading. Edited by Hans de Wit and Janet Dyk. Semeia Studies 81. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2015.

West, Gerald O. “Reading the Bible with the Marginalised: The Value/s of Contextual Bible Reading.” Stellenbosch Theological Journal 1/2 (2015): 235–61.

West, Gerald O. “Recovering the Biblical Story of Tamar: Training for Transformation, Doing Development.” Pages 135–47 in For Better, for Worse: The Role of Religion in Development Cooperation. Edited by Robert Odén. Halmstad: Swedish Mission Council, 2016.

West, Gerald O. The Stolen Bible: From Tool of Imperialism to African Icon. Leiden: Brill and Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2016.

West, Gerald O. “The Co-Optation of the Bible by ‘Church Theology’ in Post-Liberation South Africa: Returning to the Bible as a ‘Site of Struggle’.” Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 156 (2017): 185–98.

West, Gerald O. “Redaction Criticism as a Resource for the Bible as ‘a Site of Struggle’.” Old Testament Essays 30/2 (2017): 525–45.

West, Gerald O. “Senzeni Na? Speaking of God ‘What Is Right’ and the ‘Re-Turn’ of the Stigmatising Community in the Context of HIV.” Scriptura 116/2 (2017): 260–77.

West, Gerald O. “Facilitating Interpretive Resilience: The Joseph Story (Genesis 37-50) as a Site of Struggle.” Acta Theologica Supplement 26 (2018): 17–37.

West, Gerald O. “Contextual Bible Study and/as Interpretive Resilience.” In That All May Live: Essays in Honour of Nyambura J. Njoroge. Edited by Ezra Chitando and Esther Mombo. Forthcoming.

West, Gerald O. and Thulani Ndlazi. “‘Leadership and Land’: A Very Contextual Interpretation of Genesis 37-50 in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa.” Pages 175–90 in Genesis, Texts@Contexts. Edited by Athalya Brenner, Archie Chi Chung Lee, and Gale A. Yee. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010.

“You strike the women, you strike the rock!” South African History Archive. Available online: http://www.saha.org.za/women/national_womens_day.htm (accessed 28 December 2019).

* Both authors are on staff at The Ujamaa Centre. The Ujamaa Centre was established in 1989. It is located on the campus of the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Central to its liberation-theological ethos is the interface between, on the one hand, biblical and theological scholars and, on the other, local communities, particularly of the poor and marginalized. Contextual Bible Study (CBS) is a method characteristic of the Centre. For more information, see the Ujamaa Centre website.

1 Gerald O. West and Thulani Ndlazi, “‘Leadership and Land’: A Very Contextual Interpretation of Genesis 37–50 in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa,” in Genesis, Texts@Contexts, eds. Athalya Brenner et al. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010), 177–81. See also “Study 1: Land Dispossession” on the community-based website Churchland.

2 For an overview of CBS, see the Ujamaa Centre website and Gerald O. West, “Reading the Bible with the Marginalised: The Value/s of Contextual Bible Reading,” Stellenbosch Theological Journal 1/2 (2015): 235–61.

3 Gerald O. West, “Contextual Bible Study and/as Interpretive Resilience,” in That All May Live: Essays in Honour of Nyambura J. Njoroge, eds. Ezra Chitando and Esther Mombo (forthcoming).

4 West, “Reading the Bible with the Marginalised,” 236–37. The Young Christian Workers movement, with which we have worked, uses both the See-Judge-Act formulation and the “Bible Enquiry” formulation of Reality-Faith-Action; Sibusiso Gwala, “The Impact of Unemployment on the Youth of Pietermaritzburg” (MTh diss., University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2007).

5 West, “Reading the Bible with the Marginalised,” 40.

6 Teresa Okure, “Feminist Interpretation in Africa,” in Searching the Scriptures: A Feminist Introduction, ed. Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza (New York: Crossroads, 1993), 77.

7 See again, for example, Gerald O. West, “Deploying the Literary Detail of a Biblical Text (2 Samuel 13:1-22) in Search of Redemptive Masculinities,” in Interested Readers: Essays on the Hebrew Bible in Honor of David J. A. Clines, eds. James K. Aitken et al. (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013).

8 Madipoane Masenya and Hulisani Ramantswana, “Anything New under the Sun of South African Old Testament Scholarship? African Qoheleths’ Review of OTE 1994–2010,” Old Testament Essays 25 (2012); Maarman S. Tshehla, “Africa, Where Art Thou? Pondering Post-Apartheid South African New Testament Scholarship,” Neotestamentica 48/2 (2014).

9 Tinyiko S. Maluleke and Sarojini Nadar, “Alien Fraudsters in the White Academy: Agency in Gendered Colour,” Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 120 (2004).

10 Gerald O. West, The Stolen Bible: From Tool of Imperialism to African Icon (Leiden: Brill and Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2016).

11 Gerald O. West, Biblical Hermeneutics of Liberation: Modes of Reading the Bible in the South African Context (Maryknoll: Orbis Books and Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 1995), 216–38.

12 Sharon D. Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1990), 123–51.

13 Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk, 150.

14 Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk, 150.

15 See for example Irene Diamond, et al., Feminism & Foucault: Reflections on Resistance (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988).

16 Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk, 150. Welch is here engaging with Foucault’s “What Is an Author”; see Paul Rabinow, ed., The Foucault Reader (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984), 101–20.

17 Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk, 150.

18 Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk, 150; see also Seyla Benhabib and Drucilla Cornell, Feminism as Critique: On the Politics of Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

19 Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk, 150.

20 Gerald O. West, Biblical Hermeneutics of Liberation: Modes of Reading the Bible in the South African Context (Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 1991), 12–26; West, Biblical Hermeneutics of Liberation, 24–41.

21 Cornel West, “Afterword: The Politics of American Neo-Pragmatism,” in Post-Analytic Philosophy, eds. J. Rajchman and Cornel West (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 270–71.

22 Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk, 150.

23 Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk, 151.

24 West, Biblical Hermeneutics of Liberation, 69, 89-90.

25 See for example Gerald O. West, “No Integrity without Contextuality: The Presence of Particularity in Biblical Hermeneutics and Pedagogy,” Scriptura S11 (1993): 134; Gerald O. West, “Senzeni Na? Speaking of God ‘What Is Right’ and the ‘Re-Turn’ of the Stigmatising Community in the Context of HIV,” Scriptura 116/2 (2017): 271–72.

26 See for example West, “Reading the Bible with the Marginalised.”

27 “SA has highest youth unemployment rate in the world,” The Citizen. For background, see Abhijit Banerjee, et al., “Why Has Unemployment Risen in the New South Africa?,” Economics of Transition 16/4 (2008).

28 Anne Heffernan, et al., Students Must Rise: Youth Struggle in South Africa Before and Beyond Soweto ’76 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2016); Susan Booysen, Fees Must Fall: Student Revolt, Decolonisation and Governance in South Africa (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2016); Musawenkosi W. Ndlovu, #Feesmustfall and Youth Mobilisation in South Africa: Reform or Revolution? (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017); Adam Habib, Rebels and Rage: Reflecting on #Feesmustfall (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2019).

29 “The Freedom Charter,” (Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand, 1955).

30 ANC, “Economic Transformation: ANC Discussion Document 2017,” (politicsweb, 2017).

31 Government (2018), “Draft Expropriation Bill, 2019” (Government Gazette).

32 See the Abahlali baseMjondolo website and also West, The Stolen Bible, 545–55.

33 John L. Comaroff and Jean Comaroff, Of Revelation and Revolution: Christianity, Colonialism and Consciousness in South Africa (2 vols.; vol. 1; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 200–06.

34 James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1990), xii, 113–15.

35 James R. Cochrane, Circles of Dignity: Community Wisdom and Theological Reflection (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1999), 163–69.

36 Robert J. Schreiter, Constructing Local Theologies (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1985), 66.

37 Michel Foucault, Of Other Spaces: Heterotopias (1967), see “Explore Heterotopia”.

38 West, Biblical Hermeneutics of Liberation, 216–38; Gerald O. West, The Academy of the Poor: Towards a Dialogical Reading of the Bible (Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 2003), 15–45; Gerald O. West, “Newsprint Theology: Bible in the Context of HIV and AIDS,” in Out of Place: Doing Theology on the Crosscultural Brink, eds. Jione Havea and Clive Pearson (London: Equinox Publishing, 2011). Sithembiso Zwane is also reflecting on Diana Ali’s concept of “brave spaces”; Diana Ali, “Safe Spaces and Brave Spaces. Historical Context and Recommendations for Student Affairs Professionals,” NASPA Policy and Practice Series 2 (2017). Ali overtly links the concept of “safe spaces” with an emerging concept of “brave spaces”. Though Ali tends to use the “brave spaces” within the context of the classroom environment, Zwane recognizes resources here for our work within the community-based environment, and for intersecting community-classroom activism.

39 For a historical overview of the missionary-colonial dimensions of “development” see Comaroff and Comaroff, Christianity, Colonialism and Consciousness in South Africa and Of Revelation and Revolution: The Dialectics of Modernity on a South African Frontier (2 vols.; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997). For a historical overview of the colonial and postcolonial economic dimensions of “development” see Sampie Terreblanche, A History of Inequality in South Africa, 1652-2002 (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 2002).

40 For further reflections on “time” see Gerald O. West, “The Biblical Text as a Heterotopic Intercultural Site: In Search of Redemptive Masculinities,” in Bible and Transformation: The Promise of Intercultural Bible Reading (Semeia Studies 81), eds. Hans de Wit and Janet Dyk (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2015).

41 Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1991), 26.

42 Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 26.

43 Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 26.

44 Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 26.

45 Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 26.

46 Andrea Cornwall, “Introduction: New Democratic Spaces? The Politics and Dynamics of Institutionalised Participation,” IDS Bulletin 35/2 (2004): 1, 6. See also Andrea Cornwall and Vera Schatten P. Coelho, Spaces for Change? The Politics of Citizen Participation in New Democratic Arenas (London: Zed Books, 2007).

47 Gerald O. West, “Facilitating Interpretive Resilience: The Joseph Story (Genesis 37-50) as a Site of Struggle,” Acta Theologica Supplement 26 (2018).

48 Cornwall, “New Democratic Spaces?,” 2.

49 Cornwall, “New Democratic Spaces?,” 6.

50 Gerald O. West, “Recovering the Biblical Story of Tamar: Training for Transformation, Doing Development,” in For Better, for Worse: The Role of Religion in Development Cooperation, ed. Robert Odén (Halmstad: Swedish Mission Council, 2016), 136–42.

51 Paul Gifford, African Christianity: Its Public Role (London: Hurst & Company, 1998).

52 The Kairos Document of 1985 constituted an important theological articulation of protest through the collaboration of ordinary South African activists and socially engaged theologians at the height of apartheid brutality. See Kairos (1985, 1986) and West, The Stolen Bible, 445–542.

53 West, “Recovering the Biblical Story of Tamar,” 146.

54 Elelwani B. Farisani, “Land in the Old Testament : The Conflict between Ahab and Elijah (I Kings 21:1-29), and Its Significance for Our South African Context Today” (Master’s diss., University of Natal, 1993); Elelwani B. Farisani and Dorothy Farisani, “The Abuse of the Administration of Justice in 1 Kings 21:1-29 and Its Significance for Our South African Context,” Old Testament Essays 17/3 (2004); Makhosazana K. Nzimande, “Postcolonial Biblical Interpretation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: The Gebirah in the Hebrew Bible in the Light of Queen Jezebel and the Queen Mother of Lemuel”” (PhD diss., Texas Christian University, 2005); Makhosazana K. Nzimande, “Reconfiguring Jezebel: A Postcolonial Imbokodo Reading of the Story of Naboth’s Vineyard (1 Kings 21:1-16),” in African and European Readers of the Bible in Dialogue: In Quest of a Shared Meaning, eds. Hans de Wit and Gerald O. West (Leiden: Brill, 2008); Kennedy Gora, “Postcolonial Readings of 1 Kings 21:1-29 within the Context of the Struggle for Land in Zimbabwe: From Colonialism to Liberalism to Liberation, to the Present” (Master’s diss., University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2008); Ndikho Mtshiselwa, “A Re–Reading of 1 Kings 21:1–29 and Jehu’s Revolution in Dialogue with Farisani and Nzimande: Negotiating Socio-Economic Redress in South Africa,” Old Testament Essays 27/1 (2014); Obvious Vengeyi, “Land as an Inalienable Asset: Lessons from 1 Kings 21:1-29,” in Land: An Empowerment Asset for Africa: The Human Factor Perspective, ed. Claude G. Mararike (Harare: University of Zimbabwe, 2014); Eben Scheffler, “Royal Care for the Poor in Israel’s First History: The Royal Law Deuteronomian 17:14-20), Hannah’s Song (1 Samuel 2:1-10), Samuel’s Warning (1 Samuel 8:10-18), David’s Attitude (2 Samuel 24:10-24) and Ahab and Naboth (1 Kings 21) in Intertext,” Scriptura 116 (2017).

55 Though focussing on a different CBS within the series, the following essay provides a detailed analysis of this tripartite collaboration: West and Ndlazi, “Contextual Interpretation of Genesis 37-50 in Kwazulu-Natal.”

56 See “Study 2: Women & Land” on the community-based website Churchland.

57 The line-spacing between groups of questions indicates both how we group questions for report-back from small groups and how questions are grouped in textual and contextual clusters.

58 Leif E. Vaage, ed., Subversive Scriptures: Revolutionary Readings of the Christian Bible in Latin America (Valley Forge: Trinity Press International, 1997).

59 Nzimande, “Postcolonial Biblical Interpretation in Post-Apartheid South Africa”.

60 Nzimande, “Reconfiguring Jezebel.”

61 Farisani, “Land in the Old Testament.”

62 Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, “Between Movement and Academy: Feminist Biblical Studies in the Twentieth Century,” in Feminist Biblical Studies in the Twentieth Century: Scholarship and Movement, ed. Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2014), 9–12.

63 Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo (“You strike a woman, you strike a grinding stone”). For more on this rallying cry, see below.

64 For an analysis of these four phases, see West, The Stolen Bible, 318–62.

65 Itumeleng Mosala, Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology in South Africa (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989).

66 Nzimande, “Reconfiguring Jezebel,” 230.

67 Mosala, Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology, 153.

68 Nzimande, “Reconfiguring Jezebel,” 234.

69 Nzimande, “Reconfiguring Jezebel,” 234–37.

70 Nzimande, “Reconfiguring Jezebel,” 243.

71 Nzimande, “Reconfiguring Jezebel,” 243.

72 Nzimande, “Reconfiguring Jezebel,” 246–48.

73 Nzimande, “Reconfiguring Jezebel,” 243.

74 For a fuller discussion see West, “Reading the Bible with the Marginalised.”

75 Kairos, Challenge to the Church: The Kairos Document: A Theological Comment on the Political Crisis in South Africa (Braamfontein: The Kairos theologians, 1985); Kairos, The Kairos Document: Challenge to the Church: A Theological Comment on the Political Crisis in South Africa (Braamfontein: Skotaville, 1986).

76 Gwala, “The Impact of Unemployment on the Youth of Pietermaritzburg”.

77 West, The Stolen Bible, 532–35.

78 In papers presented at the Council for World Mission (CWM) Discernment and Radical Engagement (DARE) Global Forum, 19–21 June 2019 (Taipei, Taiwan), Beverley Haddad and Gerald West sought to find a phrase that would reflect aspects of “patriarchy and/as economic power”. They have coined the term “econo-patriarchy”, riffing off the more familiar “hetero-patriarchy”.

79 Mosala, Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology, 185.

80 Mosala, Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology, 40.

81 Mosala, Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology, 134.

82 Mosala, Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology, 188.

83 See Gerald West’s engagement with Mosala’s analysis, pushing beyond the prophet to forms of “people’s theology”: Gerald O. West, “Redaction Criticism as a Resource for the Bible as ‘a Site of Struggle’,” Old Testament Essays 30/2 (2017).

84 Mosala, Biblical Hermeneutics and Black Theology, 188.

85 Kairos, The Kairos Document, 34-35, note 15.