Laura J. Hunt

laura.hunt@arbor.edu

Abstract

Using cognitive metaphor theory to examine the four NT nursing metaphors (1 Thess 2:5–9; 1 Cor 3:1–3; Heb 5:11–14; 1 Pet 2:1–3), this article demonstrates that the same nursing frame can be used quite differently. The work of separating the contributions of each input space and then running the blend demonstrates how each metaphor functions and, in 1 Corinthians 3 specifically, the overlaps and gaps that arise in the analysis explain previous discrepant interpretations as well as a new way forward. The nursing frame itself incorporates many different primary metaphors grounded in embodied experiences, but not all of these are activated in every context. Each analysis concludes by pointing out its focus on specific blends and suggests the purpose of this focus through the use of social identity theory.

Keywords

Cognitive metaphor theory; nursing; social identity theory; mother; wet nurse

“What the mischief, then, is the reason for corrupting the nobility of body and mind of a newly born human being, formed from gifted seeds, by the alien and degenerate nourishment of another’s milk?” (Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 12.1.17 [Rolfe, LCL])

The canonical New Testament includes four metaphors that invoke milk and nursing (1 Thess 2:5–9; 1 Cor 3:1–3; Heb 5:11–14; 1 Pet 2:1–3). This article proposes that, although they all rely on the same embodied practice, cognitive metaphor theory (CMT) demonstrates that they project quite different aspects of that practice into the blend, such that meaning in one passage cannot be conflated with another. After setting out some key elements of CMT, each passage will be analysed in a process called running the blend. In each case, a different blend unfolds: Paul and his companions are a tireless, loving mother giving of herself; the Corinthians are unruly and even sassy children eating unhealthy food; the author of Hebrews warns that baby Christ-followers are in mortal danger if they do not grow; Peter’s addressees are to cling to God, drinking the Father’s milk, the Lord.

Cognitive processes that allow human beings to use metaphors are grounded in embodied experiences.[1] In early childhood, parallel neural pathways are constructed for simultaneously occurring experiences, creating the basis for metaphors such as IDEAS ARE FOOD, DESIRE IS HUNGER, AFFECTION IS WARMTH, COMMUNICATION IS FEEDING, ACQUIRING IDEAS IS EATING.[2] Out of these come more complex elaborations such as those that ground nursing metaphors: ACCEPTING IS SWALLOWING, MORAL GROWTH IS PHYSICAL GROWTH, MORALITY IS PURITY, ONGOING CAUSATION IS NOURISHING, SOCIAL GROUP IS A FAMILY, and SOCIAL FUNCTIONING IS PHYSICAL HEALTH.[3] Because each metaphor prompts a different blend, however, each metaphor also invokes different vital relations. Although all rely on IDEAS ARE FOOD, 1 Thessalonians 2:7 is especially keyed to SOCIAL GROUP IS A FAMILY; 1 Corinthians 3:1–3 relies on ONGOING CAUSATION IS NOURISHING and SOCIAL FUNCTIONING IS PHYSICAL HEALTH; in Hebrews 5:11–14, MORAL GROWTH IS PHYSICAL GROWTH is especially important, and 1 Peter 2:1–3 turns on DESIRE IS HUNGER.

After explaining how these metaphors mean what they do, the article will then go on in each case to very briefly suggest why the authors might have expressed their thoughts using these metaphors. As Penniman notes, “early Christian engagement with the ideals of paideia involved complex appeals to nourishment and breast-feeding as a regulatory symbol—a symbol with such structuring power, such capaciousness of meaning, that it could be put to work on behalf of quite divergent configurations of social identity.”[4] However, he never strictly defines this last term. Although there is not space in this article to go into detailed analysis, in each example I will briefly mention some possible effects on the hearers of each text, particularly their cognitive, evaluative, and emotional attachments to their social identity as Christ-followers.[5] These effects can at this stage only be asserted with the hopes of more substantive engagement in the future.

Mapping Conceptual Blends

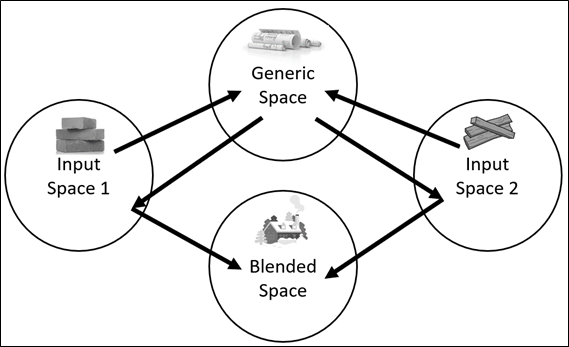

Fauconnier and Turner’s network model involves four conceptual spaces to structure metaphors, rather than the (perhaps more common) terms “source” and “target” (Figure 1).[6]

The first input space provides one set of building materials (represented by bricks in the figure).[7] In this space, the metaphor calls up one culturally known set of objects and behaviours: a frame, or in other words, “tightly linked chunks of conceptual structure which get evoked together.”[8] This potentially limitless set of referents is set alongside another frame in the second input space (represented in Figure 1 by wood). Then, elements of each frame are correlated with one another in the generic space, matched up in an orderly way, following the relations in the input spaces, somewhat like a blueprint (top set of two arrows in Figure 1). Finally, all the elements come together in the blended space. The blend is constrained by the available materials from the two input spaces. It follows the schema from the generic space, but also selectively includes elements from each input frame as its structure emerges (bottom set of four arrows, Figure 1).

In this article, the first input space will always be occupied by nursing, a frame which entails a network of culturally related elements such as mothers, wet nurses, and milk. The second conceptual space contains a second frame, in this case the aspect of reality that the author wants to describe. By using a metaphor, each author selectively projects relationships and affections from a nursing frame and blends them with the situation of the community addressed in the letter. This article will argue that each author does so to quite different effect.

The Loving Wet Nurse Mother: 1 Thessalonians 2:7b–9

As if a wet nurse were tending to her own children, in the same way, yearning over you, we became determined to share with you not only God’s good news but also our very selves, because you became so dear to us. For you remember, brothers and sisters, our toil and moil. While working night and day so we would not burden any of you, we preached God’s good news to you.[9]

This example most particularly demonstrates the way the generic space and the subsequent blended space constrain the elements of the first and second input frames so that certain elements of each frame are selectively projected into the structure that emerges in the blend. Once the blend has been described, the primary metaphors that ground it will become more obvious. These will then guide some preliminary conclusions about the cognitive, emotional, and evaluative work done by the metaphor for the sake of the addressees’ social identity.

In the nursing frame, the word trophos in verse 7b refers to a nursing woman, often a slave or one paid for her services feeding others’ babies, i.e., a wet nurse (Gen 35:8; 4 Kgdms 11:2; 2 Ch 22:11; Isa 49:23).[10] The word order prompts the evocation of a wet nursing frame before Paul adds the phrase, “her own children.” With this redirection, the slave feeding the master’s child becomes a wet nurse feeding not someone else’s baby, but her own.[11]

While the ancient world knew of the love that could develop between a wet nurse and her charges, nursing after childbirth was understood to enhance the affection between a mother and her child.[12] Plutarch points out that Nature’s whole system of reproduction would be useless if she “had not implanted in mothers affection and care for their offspring” (Moralia: On Affection for Offspring 3.496A [Helmbold, LCL]). Philo is aware that a mother will suffer pain if she is not able to nurse her baby. He grounds a mother’s affection for her child in that physical fact and argues that not only baby animals but also infants ought not be separated from their mothers at least for a week, because this milk that nature provides is both “abundant” and a “means of enjoyment” (On the Virtues 25.128–33 [Colson, LCL]).[13] Aulus Gellius gives Favorinus a speech in which he argues that just as the blood that forms a child in the mother’s womb comes from the father’s seed, so does the milk, but this does not negate some contribution “from the body and mind of the mother as well” (Attic Nights 12.1.20). Therefore, to separate a baby from its mother’s milk is to cut off the bond not only between child and mother, but from the father, too. Furthermore, Favorinus argues for a connection between the virtue of the woman who nurses and the subsequent virtue of the child. He strenuously objects to the practice of hiring slaves or women of low status as wet nurses:

What the mischief, then, is the reason for corrupting the nobility of body and mind of a newly born human being, formed from gifted seeds, by the alien and degenerate nourishment of another’s milk? Especially if she whom you employ to furnish the milk is either a slave or of servile origin and, as usually happens, of a foreign and barbarous nation, if she is dishonest, ugly, unchaste and a wine-bibber; for as a rule anyone who has milk at the time is employed and no distinction made. Shall we then allow this child of ours to be infected with some dangerous contagion and to draw a spirit into its mind and body from a body and mind of the worst character? (Attic Nights 12.1.17-20 [Rolfe, LCL])

He wraps up his objections by quoting no less an expert than Vergil on the matter: Dido accuses Aeneas of being heartless because “Hyrcanian tigeresses” nursed him (Aen. 4.366 [Fairclough, Goold, LCL]). In these last two cases, the character of the nurse affects the character of the child through the quality of the milk.[14]

Gellius presents us with this story told from the perspective of a philosopher giving advice to his disciple who has just become a father (Attic Nights 12.1.1–2). It is the viewpoint of an authority, focusing on the milk of the mother as it affects the character and the affections of the child. In all these examples, ancient authors expected mothers to feel a specific attachment grounded in nature to their own children. These expectations were part of the nursing frame in the ancient world.

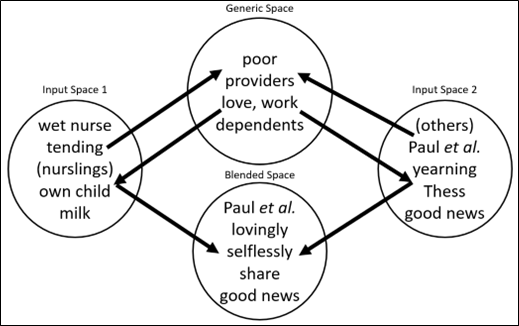

The contrast in the first input space between women who nurse others’ babies and women who nurse their own mirrors a similar contrast between Paul and his adversaries. Verses 5–7b elaborate the distinctions. Weima translates these verses as three denials followed by three parenthetical responses and an affirmation: “For we never came with a word of flattery—as you know—nor with a motive of greed,—God is our witness!—nor were we demanding honor from people, neither from you nor from others,—even though we could have insisted on our importance as apostles of Christ—but we became infants[15] among you.”[16] Thus, Paul repudiates any motives of greed (v. 5),[17] hubris (v. 6),[18] or harshness.[19] A few verses earlier, Paul had distanced himself and his companions from teachers whose deceitful appeals were based on error or immorality (v. 3). Thus, both contrasts are mapped in the generic space: the first between a woman’s care for nurslings versus her own child and the second between the care for the Thessalonians felt by Paul and his companions versus that exhibited by Paul’s opponents (Figure 2).

Note that, in the input spaces, one wet nurse with an unspecified number of charges maps to an unspecified number of false teachers with the Thessalonians. There may be more than one false teacher while there is only one wet nurse, and the number of Thessalonians may not match the imagined number of the wet nurse’s charges. Also in the blend, the one nursing mother with one or more children maps to Paul and his companions (the “we” in this passage) with the Thessalonians. Again, the number of caregivers and care receivers in the first input space does not match the numbers in the second input space. Some scholars argue that Paul is only talking about himself even though he uses the plural.[20] However, compression is a common “vital relation” in mapping mental spaces in CMT.[21] Thus, it is not necessary to assume the metaphor is only about Paul. The roles are preserved in the generic space, even while the number of actors from each input is not (Figure 2).[22] Several teachers are mapped on to just one woman.

Similarly, but projected from the second input space, the many Thessalonians (v. 7b) are mapped to the few children that a mother might nurse at one time. The increased burden on a mother with more than one child highlights Paul’s selfless toil. Paul and his companions as they care for the Christ-followers in Thessalonica have, by means of this blend, become a mother caring not just for one child, but for many.

As the blend proceeds, Paul compounds his expression of love for the Thessalonians with this work done for them. When an infant is drinking milk, of course, the mother is giving of her very body.[23] Paul, similarly, says that he and his companions gave their very selves (v. 8). But Paul also describes their “toil and moil” to not be a burden. The “toil and moil” of “working night and day” of verse 9, especially given its gar (for), I take as part of this metaphor, even though exegetes often move on in this verse to a discussion of Paul’s night and day work at his trade and never connect work with nursing.[24] However, working night and day is not only what Paul et al. do, but what they have in common with nursing mothers.[25]

A blend develops from the overlap of the two input frames as they are defined in the text. The relations in one frame may demand the projection of a similar element from the other frame. The sharing of “God’s good news” (v. 7) alongside the sharing of their “very selves” demands the projection of the milk given by the mother into the blend, although that part of the nursing frame is not otherwise entailed (Figure 2). Yet in the blend, the gospel becomes that which was necessary for the Thessalonians, the food that they required at the beginning of their faith and service to God (1:3, 8–10). The emergent structure highlights the apostles’ exhausting, selfless work done out of love to sustain the lives of the letter’s recipients.[26]

McNeel and Burke suggest that the pain of the mother and the vulnerability of the child when separated may also be entailed in this blend since Paul is now separated from the Thessalonians (2:17–3:5).[27] Certainly, Paul’s language echoes the feelings of parents for their offspring. However, since both father and sibling language come between the two passages (2:11–16), I prefer the slightly more reserved suggestion that Paul is expressing parental love in 2:17–20, rather than specifically maternal love.

The nursing metaphor in 1 Thessalonians 2:7, then, relies on several of the primary metaphors mentioned at the beginning of the article. These primary metaphors raise primary scenes, “early and pervasive correlations—often specifically between physical experiential input and subjective judgment or assessment.”[28] This blend relies on IDEAS ARE FOOD and COMMUNICATION IS FEEDING. “The gospel of God” (vv. 2, 8) or “the gospel” (v. 4) have been mentioned three times in vv. 1–9 as Paul and the apostles spoke it (vv. 2, 4) and shared it (v. 8). The gospel, then, is the food that was as necessary to the Thessalonians as milk is for a baby, and the speaking and sharing of it is the feeding done by Paul and his companions. Furthermore, this passage highlights the primary metaphor SOCIAL GROUP IS A FAMILY. In this case, the Thessalonians are all siblings (v.1), and while Paul and his companions take the role of a mother, the passage carefully highlights the nurturing aspects of motherhood rather than the hierarchical.

Néstor Míguez, in fact, suggests “the strategy of the apostles involves being in their midst providing food instead of being above them, extracting a revenue.”[29] However, the giving of food in the ancient world entailed the authority of the provider.[30] Furthermore, discussions about nursing could be used to extend male authority.[31] Thus, authority is implicated in the nursing frame. Still, by selectively highlighting only the act of feeding, the text focuses on the work and the love of the givers and not on their authority, however implicit it might be. Note, too, that the passage does not mention the response of the infants/Thessalonians at all.[32]

If Penniman is correct that social identity can be implicated in nursing metaphors, what effect does the metaphor just discussed have on the recipients of the letter? There is little additional cognitive information for them in 1 Thessalonians 2:1–9 except to highlight the value of the gospel as the food that they required. Even that, though, is more evaluative than cognitive, raising their estimation of the value of the apostles’ work based on the value of the substance they provide. So, too, is the blend’s emphasis on Paul and his companions as the better mother, better than alternative sources of information as they yearned for the good of their listeners and worked day and night not to burden them. Additionally, the lack of any element of judgment or evaluation of the infants (quite different from other nursing metaphors examined in this article) invites the Thessalonians not only to evaluate the apostles as the better mother, but to emotionally respond to their love. Thus, the addressees are asked to esteem Paul’s teaching, his and his companions’ time among them, and their mutual bond of affection. This increases the likelihood that the addressees will continue to imitate Paul and “the Lord” (1 Thess 1:6).[33]

Children Sassing Mother: 1 Corinthians 3:1–3

And as for me, brothers and sisters, I could not speak to you as spiritual but as fleshy people (sarkinos), as babies in Christ. I fed you milk, not food; for you were not yet able. But you are still not able now, for you are still fleshly (sarkikos). For where there is jealousy and strife among you, are you not fleshly and living according to human standards?[34]

In the 1 Thess 2:7 nursing metaphor, quite a bit of the structure that emerged in the blend came from the first input space where the mention of a wet nurse entailed a contrast between nurslings and a mother’s own children. Structure, however, can be projected from either input space.[35] In 1 Corinthians 3:1–3, in fact, incomplete structural relations within the input spaces leave much in the metaphor undefined. The apparent mismatch between input spaces (see below) often leads to confusion in the commentaries. Furthermore, the tendency to explain a metaphor by using it sometimes complicates the discussion.

James M. M. Francis, for example, says that “Paul is rebuking his readers not because they are babies still, and had not progressed further, but because they were in fact being childish, a condition contrary to being spiritual.”[36] This, however, does not define what it might mean for Paul’s readers to be babies, and childishness is not clearly part of either input space. Similarly, Anthony C. Thiselton asks, “But does Paul have in mind the image of children who need to grow, or that of infantile adults who need to adjust their attitude?”[37] In this case, children, growing, and infantile come from the first input space, and adults and attitude adjustment from the second. The sentence smuggles the image of children from the first input space into the second in the guise of infantile behaviour. Both descriptions attempt to run the blend before the input spaces and the generic structures have been separated and mapped.

A division between more and less spiritual, or more and less mature Christ-followers “became the inescapable temptation and dominant issue” in early readings.[38]On the face of it, 1 Corinthians 3:1–3 can be construed as a critique of the Corinthians who heard the basic story about Jesus, believed, but then did not progress any further, so that Paul cannot give them more advanced instruction.[39] This critique would cohere with Philo’s use of the same metaphor as he calls men to advance beyond “the preliminary stages of school-learning.”[40]

However, a hierarchical structure of advancement for Christ-followers, “pass/fail and honors,” is unlikely in a letter already addressing problematic divisions.[41] Furthermore, it would be odd for Paul to claim that he cannot give the Corinthians advanced knowledge when the rest of the letter contains detailed instructions on a wide variety of topics.[42] Also, a critique of the Corinthians’ lack of progress since Paul’s first presentation of the gospel does not take into account some of Paul’s other statements, such as in 1:4–7, where he confirms the Corinthians’ partnership with Christ.[43]

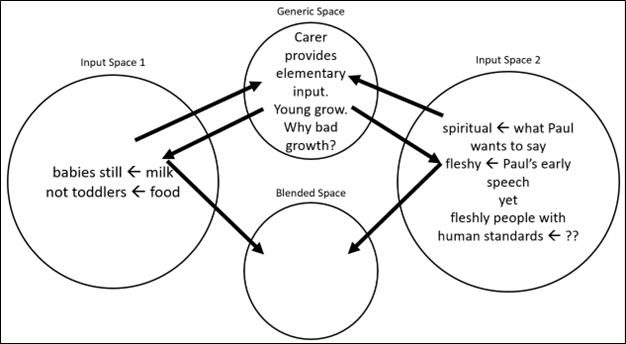

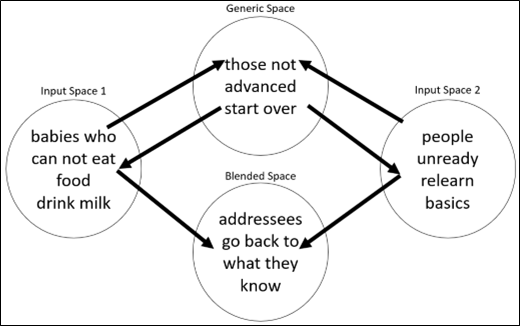

The first input space (Figure 3) includes babies, milk, food, and the word eti (yet, still, v. 2) which implies that the babies at some point will eat food. The relations that connect these are simple: babies must still be fed milk because they are not able to digest food, but that state is not permanent. The second input space includes the speech suited to spiritual people that Paul wants to make, Paul’s early speech that was tailored to the Corinthians as fleshy people, and the fleshly and human results of their choices that make them unsuitable for Paul’s desired speech to them now.

Before meeting Paul, the Corinthians were sarkinos, living on their own without the God of Israel.[44] Paul’s preaching brought them into the realm of Christ, the realm of the Spirit. However, they are still not spiritual. They are sarkikos. More than just fleshy, the Corinthians are displaying fleshly selfishness (jealousy and rivalry, v. 3), showing that they have rejected Paul’s wisdom.[45] So while, after their initial faith in Christ, they might have been expected to grow from new disciples into spiritual people, instead they have grown from new disciples into fleshly people who are still arguing over status, dos and don’ts, and loyalty to various leaders.

The “yet” in the second input space requires explanation. One might have expected Paul to say, “But you are still not able now, for you are still fleshy (sarkinos),” implying that Paul has to keep explaining the basics to them over and over again. This interpretation would cohere with Philo’s previously-mentioned use of the same metaphor (n. 40). Instead, Paul calls the Corinthians not “still fleshy,” but “still fleshly” (sarkikos). This reference to a fleshliness, related to their original fleshiness (eti) yet also somehow different (sarkikos not sarkinos), opens a conceptual spot in the second input space.

Since “scalar, causal, and aspectual structure must be preserved in metaphoric mappings,” relations project slots into the generic space that demand to be matched from the other input space to create the emerging structure.[46] Thus, in the first input space, those who are still babies drink milk but are expected to eventually be ready for food (Figure 3). In the second input space, though, those fleshy people heard Paul’s words and were expected to eventually become spiritual and therefore ready for Paul to speak to them as spiritual people. They have instead grown into fleshly people living according to human standards. In both cases (generic space), the carer first provided elementary input and the young ones grew. However, since the ancient world knew that good input causes good growth, the metaphor raises the question: what caused the bad growth? As mentioned above, in the ancient world, the milk one drinks provides not only physical nourishment but also passes on the character of the woman producing the milk. If the Corinthians are not behaving in ways that are aligned with Paul’s character, what milk, what speech, has prompted this unhealthy growth?

This dilemma can be solved by unpacking a Hebrew Bible allusion not usually noted, Isaiah 28:7–13. Literary allusions require, minimally, (1) a marker, (2) pointing to a known text, (3) an interpretation of that known text, (4) a re-interpretation of the known text in the new (immediate) context, and (5) a re-interpretation of the new text as a whole based on broader contrasts and comparisons that now appear between the known text and the new use of that text.[47] There is no question that Isaiah is a known text for Paul.[48] Furthermore, he has just quoted Isaiah 40:13 (1 Cor 2:16) before moving into the metaphor under discussion. With the activation of Isaiah as an “evoked text,” the whole of the book becomes available for further allusions.[49] Thus, the mention of weaned babies can become a marker for the passage in Isaiah referring to weaned babies. Paul, in fact, comes back to an adjacent section of Isaiah in 1 Corinthians 14:21 where he quotes Isaiah 28:11–12.[50]

The interpretation of Isaiah 28 is debated, however, both with regards to who is intended to speak each of these phrases, and the meaning of the phrases themselves (particularly 28:10, 13).[51] For the purposes of the allusion, verses 9–10 seem most relevant, and the CEB helpfully preserves the sound of the Hebrew:

To whom will God teach knowledge? To whom will he explain the message? To those just weaned from milk? To those who have hardly outgrown the breast? It is “tsav letsav, tsav letsav; qav leqav, qav leqav,” a little of this, a little of that.

According to Dekker, whose allocation of speakers I follow here, the prophet Isaiah is mimicking the Jerusalem priests who mock Isaiah’s attempts to teach them the word of the Lord.[52] Isaiah repeats their complaints as they accuse him of treating them like just-weaned babies. The priests claim they are too mature for the way Isaiah is speaking to them.[53]

The sound pattern in verse 10 could simply be baby talk, a series of meaningless sounds one makes to infants.[54] This, it seems to me, fits the context better than Dekker’s paraphrased translation, “For it is all filth that he vomits over us,” which minimises the significance of a repetition of sounds in the context of the hendiadys in verse 9 referencing just-weaned children.[55] But if John Emerton’s suggestion (on which Dekker relies) that tsav alludes to tso’ah (v. 8; filth, excrement) and qav alludes to qay’ (v. 8; vomit) is correct (and note that it is supported by several second-century CE witnesses), the patterned repetition of sounds indicative of baby talk points to the way parents speak around little ones about their bodily functions: “For ‘poopoo and poopoo, poopoo and poopoo; spit up and spit up, spit up and spit up, a little here, a little there.’”[56] Isaiah does not specify why these infants might be producing so much poo and spit though.

Yet Galen notes that “everyone, even if poorly endowed intellectually, is aware that just as experience teaches many other things, so too it teaches about foods that are digestible and indigestible, wholesome and unwholesome, and laxative and constipating” (On the Properties of Foodstuffs, 1.457).[57] Connections between the food eaten and the working of the body were clear in the ancient world. Soranus, furthermore, suggests that upon weaning, “One should not alienate the child from anything: neither from the drinking of wine, water, cold and hot things, nor from anything fatty, for it is good to create a habit for useful things straight from the beginning” (Gynecology 11.21.48 [41.117]).[58] Neither Isaiah, obviously, nor Paul, of course, can be expected to have read Galen or Soranus. Still, these quotes reassure us that connections between eating and digestion are not uniquely a product of the modern age.

The last phrase of Isaiah 28:10 may also parallel verse 8: “without [a clean] place” (8); “a little here, a little there” (10, 13). The assertion that there is no place without filthy vomit around the priests and prophets (v. 8) suggests that verse 10 refers to all the cleanup required around infants, cleaning up some poo here and some spit up there.[59]

To summarise the metaphorical blend in Isaiah 28:7–10:

- First Input Space: toddlers who poo and spit up and need someone to come after them cleaning up. The metaphor does not specify why the toddlers are not digesting properly.

- Second Input Space: Jerusalem leaders get sick but mock the idea of following Isaiah’s messages which would require cleaning up their behaviour as well as their environment. Their sickness happens because of the wine and beer they are drinking.

- Generic Space: people produce filth with some tension around whether it needs cleaning up. The filth is produced because of poor input.

- Blended Space: Isaiah points out that the Jerusalem leaders are stubbornly insisting that they do not need correction, while behaving like toddlers with poor eating habits, who need someone to clean up after them.

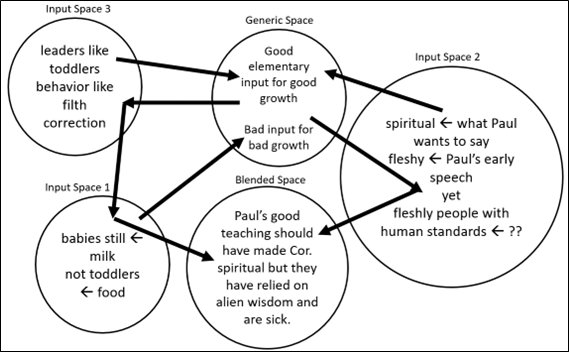

This interpretation of Isaiah 28:7–10 (the known text) suggests that Paul sees in this passage of Isaiah a mirror of his own frustration with the Corinthians. The Corinthians’ self-understanding (at least as Paul deduces it to be) is mapped to an infant who starts out with good milk from a loving mother but grows into a toddler who has rejected mother’s food. Paul responds to the Corinthians as though they, too, are telling him, “We are too mature for this elementary teaching you are offering us.”[60] Just as the priests and prophets in Jerusalem are drinking beverages that make them sick, the Corinthians have found other sources of wisdom which are not leading to the health of the community.[61] The 1 Corinthians allusion to the Isaiah 28 metaphor answers the question the original metaphor asked (Figure 4[62]): What would cause a baby to grow poorly? What would cause Corinthians to grow into fleshly instead of spiritual people? In both cases, absorbing the wrong input makes one sick.[63]

So it follows, then, that the rest of the letter is filled with Paul’s detailed responses to the minutia of Christian living that the Corinthians were arguing over (e.g., 7:1). Furthermore, “Paul’s appeal to milk and solid food was more than just suggestive of paideia but was, in fact, structured by the conceptual framework, social or political sanctions, and embodied practices that made paideia an enduring cultural phenomenon in the ancient world.”[64] If the Corinthians would settle into their relationship with Paul and absorb his paideia, they, and he, would be able to share in a more mature exchange, perhaps such as his more hands-off encouragement to the Philippians (1:9–11; 3:15, 17). Instead, he feels obliged to send the Corinthians detailed directions—perhaps we might even call them a list of no-nos.

The failure of the Corinthians is not that they have remained infants. Rather they have missed the ethical entailments of their knowledge that might propel them into adulthood; they have grown into toddlers who refuse to properly digest the food that Paul, their mother, has provided.[65] The Corinthians have grown beyond both their dependence on Paul and their desire for his teaching because they have found their own sources of so-called wisdom.[66] They are lovers of wisdom (1 Cor 1:17–2:5) but not the right kind (2:6–15). They are therefore living according to human standards (3:3), instead of becoming the spiritual people they claim to be.

Although the metaphor in 1 Corinthians 3:1–3 relies on nursing in its first input space, the primary metaphors that it develops are quite different from those in 1 Thess 2:7b–9. Both highlight IDEAS ARE FOOD and COMMUNICATION IS FEEDING. However, Paul also relies on ACQUIRING IDEAS IS EATING to show that the ongoing reliance of the Corinthians on wisdom from sources other than himself is causing problems with their growth (ONGOING CAUSATION IS NOURISHING). Ultimately, this metaphor highlights the poor choices the body of Christ in Corinth is making for the sources of their food/ideas (MORAL GROWTH IS PHYSICAL GROWTH; SOCIAL FUNCTIONING IS PHYSICAL HEALTH).[67] The Corinthians’ reliance on alternative sources of wisdom is creating unhealthiness within the community. Paul’s good teaching should have made them spiritual, but they have relied on alien wisdom and are sick (Figure 4).

As to the effects on the Corinthians’ social identity, they should understand themselves to have gotten off track (cognitive social identity). They are shamed for their current state of paideia (emotional social identity). And that shame is intended to drive them to re-evaluate themselves as siblings. They were mothered (and fathered; 4:14–21) by Paul and, therefore, they should return to his teaching and to him as their model (4:16).[68]

Babies on Fire: Hebrews 5:11–14

About whom [Melchizedek], there is a speech that is long and difficult for us to give, because you have become lazy listeners. For although by now you should even have been teachers, you need someone to teach you the beginning basics of God’s oracles; you have gone back to needing milk, not solid food. For everyone who enjoys milk is untrained in the word of righteousness; for he is an infant. But adults have solid food; they are those whom age has trained to discern the difference between right and wrong.[69]

As in 1 Corinthians, in this passage, the structure of the generic space hinges on the kind of food eaten.[70] However, instead of three kinds of food, there are only two: Infants drink milk; adults eat solid food. In the second input space, new children of God (Heb 2:10; cf. 3:1) are untrained while the diligent (6:11) know “the difference between right and wrong,” an expression that references maturity particularly with regard to righteousness (v. 13).[71] The perfect verbs in verses 11 and 12 reinforce the suggestion in verse 12 that the best way forward would be to start over at the beginning.[72] Adults who used to eat solid food (6:4–5) not only prefer milk, but need it. The author sets up a metaphor that seems simple:

The first input space contributes babies who should be grown enough for solid food, but somehow are not (Figure 5). The second input space holds the addressees who ought to be able to handle the discussion of Melchizedek to follow, but are, according to the author, too lazy to do so (v. 11). Instead, they require further discussions about God’s oracles.[73] The relationships are preserved in the generic space where those who have not advanced must go back to the beginning instead of moving on as they should. The blend, then, would seem simple: the author will teach his listeners beginning material all over again because they are not yet able to discern right from wrong.

However, Hebrews 6:1–12 does something surprising with this initial nursing metaphor. The nursing frame is carried forward through 6:4–5 with the repeated verb “taste,” as the author brings up the “heavenly gift, the noble word of God, and the powers of the coming age,” and the Holy Spirit in which the listeners have shared. He then introduces an agricultural metaphor.[74]

For the land, when it drinks the frequent rain falling on it, brings forth vegetation useful to its cultivators, too and thus has a share in the blessing given by God. But if it produces thorns and thistles, it is worthless and under a curse; it will end in fire (Heb 6:7–8).

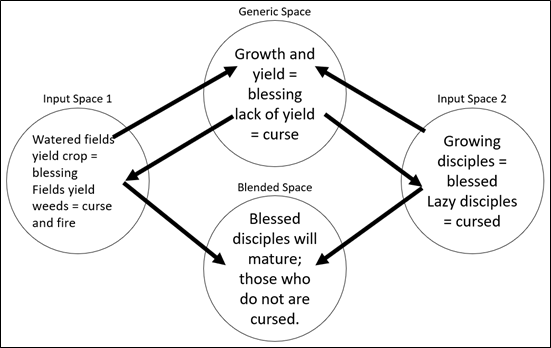

The verb “to drink” echoes the tasting from verse 4 connecting the first input space from this new metaphor to the first input space of the nursing frame.[75] Babies taste milk; the addressees of the letter absorb God’s gift; the ground absorbs water. These parallel relationships allow the metaphors to be mapped one to another. In the agricultural metaphor, however, the structure hinges not on different inputs, as in the nursing metaphor, but rather on different outputs (Figure 6). When the land produces a crop, it evidences God’s blessing, but when it produces thorns and thistles, it evidences a curse. In the second input space of the agricultural metaphor, the parallel focus is on the output from the disciples.

The reference to the ground bringing forth also overlaps with the first metaphor as “to bring forth” fits the nursing frame as well. However, a mismatch of relations in the two input spaces causes difficulty. In the first metaphor, the addressees of the letter are mapped onto the babies who were born. In the second metaphor, however, the addressees of the letter are mapped onto the ground which brings forth. In this case, the inputs are redoubled.[76] Disciples who were born now give birth themselves. But the author questions whether what is born of them is blessing or curse.

Blessings and curses connect the agricultural metaphor with the blessedness of the garden of Eden in which life began, and the curse on the earth with which it ended (thorns and thistles, Gen 3:18 LXX).[77] “Dead works” (6:1), too, may refer not to cultic practices but to sin (9:14) which in the garden led to expulsion and death.[78] Death, in fact, is a key adversary in Hebrews (as is sin).[79]

In this complex passage, then, the structures of the two metaphors are contrasted to shame the addressees for believing they could repeatedly listen to basic instructions without wrestling with difficult teaching or challenging ethics.[80] In the nursing metaphor, those who have not advanced see no harm in lazily (5:11; 6:12) going back to their beginnings (Figure 5). The outcome of this choice is the comfort of going back to more milk. In the agricultural metaphor, however, ground that drinks the rain and only produces weeds will be burned (Figure 6). By switching metaphors, the author declares the first metaphor invalid. He shuts the door completely on the possibility that the disciples can stay forever babies enjoying milk by demonstrating that regression does not mean more milk, but fire. After this shock, the author cajoles them (6:9–11) to move forward in both learning and application.[81]

The structures of the two metaphors carry the bulk of the contrast, but the viewpoints contrast as well. In the first, the author stands outside the family, judging the adults who prefer to be infants, using 2nd person plural verbs (5:11–12).[82] As the text moves from the first metaphor to the second, the author joins the auditors with 1st person plural verbs, committing himself to staying with the addressees as they mature (6:1–3).[83] The fire metaphor is mitigated somewhat by the author’s use of the 3rd person plural (6:4–6), which allows him then to go on to reassure his auditors that they are not among those whose end is fire.[84] He then firmly expresses confidence (6:9) that God will allow the auditors to attain the maturity they need to handle the upcoming discussion of the author’s new information, Jesus as “a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek” (7:20).[85] And he personalises his appeal briefly in 6:11 with the use of a 2nd person singular pronoun. He is sure that, if they are not lazy, but “demonstrate the same zeal towards assuring [their] hope until the end” (6:11–12), they will mature into the kind of productive faith that lets them “become imitators of those who, through faithfulness and patience, are inheriting the promises” (6:12).[86]

This passage relies on common cognitive connections such as IDEAS ARE FOOD, COMMUNICATION IS FEEDING, and ACQUIRING IDEAS IS EATING. These cover the situation at the beginning of Hebrews 5:11, where the author complains that despite his having provided information that the addressees absorbed, they have not grown as expected. Thus, the dispute centers around two further cognitive metaphors: MORAL GROWTH IS PHYSICAL GROWTH (and its corollary, POOR MORAL GROWTH IS POOR PHYSICAL GROWTH), and SOCIAL FUNCTIONING IS PHYSICAL HEALTH.[87] When the passage shifts to social functioning, however, the cognitive basis shifts to agricultural metaphors, such as PEOPLE ARE GROUND, PRODUCTIVE GROUP PARTICIPATION IS CROP PRODUCTION, and IMMATURITY IS WEED PRODUCTION.[88] These basic components provide the grounding which allows the author to communicate his concerns in ways that cognitively connect with the addressees’ embodied experiences.

In addition to these cognitive effects, the social identity of the addressees is activated both emotionally and evaluatively. The addressees are shamed for their lack of maturity, and the second metaphor pits the horror of fire against the comfort of warm milk. This emotionally charged passage is designed to push those who hear it away from their previous unwillingness to deepen their group commitment, and to categorise themselves more firmly among those about whom the author “is convinced of better things” (Heb 6:9).

The Milk of God: 1 Peter 2:1–3

Therefore, having stripped off all malice and every deceit and hypocrisies and jealousies and all evil speech, like new-born infants long for the reasoning (logikos), unadulterated milk, so that with its help you might grow into salvation, assuming you have tasted that the Lord is fine (chrēstos).

Input spaces in metaphors can clash, and these clashes can be resolved in several different ways. In 1 Thessalonians, the relations in the first input space became the primary structure of the blend.[89] The teacher-student connection that the Thessalonians might have felt was amplified by the affection and investment of a wet nurse for her own child. In the 1 Corinthians metaphor, clashes between the first input space with only two types of children (babies and toddlers) and the second input space with three types of Christ-followers (spiritual, fleshy, and fleshly) required another input space from Isaiah to creatively solve the clash.[90] In Hebrews, two consecutive metaphors clashed with each other. In the first, the structure of the nursing frame controlled the description of the followers of Christ and proposed that they could continue to be treated as beginners as long as necessary. In the second, the structure of the agricultural frame responded that those who do not mature within the Christ-following community are under a curse. Clashes between input spaces can be resolved in all of these ways: by choosing one structure over another, by creatively merging the two, or by bringing them both separately into the blend.[91] In each case, the communicative impact of the blended structure is enhanced by the projection or combination of relations from the originating frames.[92]

It is helpful, for this last metaphor, to examine the initial clash first. The first input space echoes many discussions in the ancient world where men gave advice on the proper nursing of infants.[93] In the second input space, Peter, as a trusted friend, advises the Christians. The mapping of Christians to babies clashes around the issue of agency: the agency available to the Christians Peter addresses does not directly correspond to the helplessness of the infant in the first input space.[94] This creates two distinct possibilities for the generic space: people who are given sustenance, or people who choose their own sustenance. Yet the author does not seem to want his readers to choose between the two. This same paradox is evident throughout 1 Peter: Christians are both responsible for their own growth and dependent on God.[95]

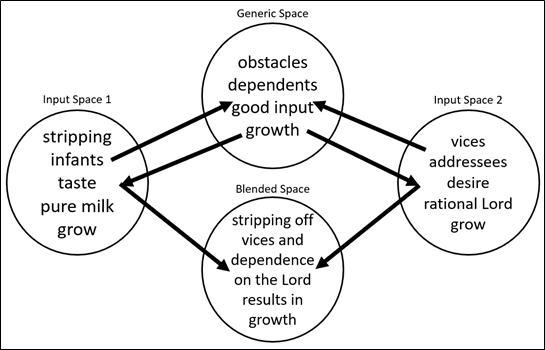

Another clash arises with reference to apotithēmi (v. 1), which I have translated “stripped off” to hint at the polysemy of the word whose frames of use include that of undressing.[96] The difficulty in the mapping of the metaphor, however, is that the participle refers to the addressees of the letter, who are then also compared to newborns. Newborns, of course, do not yet know to pluck at mother’s peplos in the universal sign for, “I’m hungry!”[97] Furthermore, the undressing that happens in the first input space is of the mother, while in the second it is the Christians who are told to remove their own vices. Still, the previous compression of helplessness with agency suggests compression in this case, too, such that the insistent tugging of babies (aided by mothers) corresponds to the necessity for Christians to remove vices from their own lives (aided by God).[98]

The first input space, then, includes the removal of clothes, newborns who desire milk which causes them to grow, and milk that must be unadulterated (Figure 7). “Unadulterated” fits this first space as a quality more realistically adhering to milk than to the Lord. However, since rationality is not a usual evaluation of milk, logikos will go in the second input space to be discussed below. Purity, the positive attribution of milk that is unadulterated, is an initial characteristic of the milk desired (v. 2), but it is also evident in the milk’s taste (v. 3). Chrēstos, fine (v. 3), was used by Plutarch, for example, to describe high quality wine (Mor. 240D2).[99] In this space, then, newborns desire the unadulterated milk which causes them to grow. The milk is fine, which the babies know because they have tasted it.

The second input space is only briefly sketched out: the addressees (second person plural verbs), salvation, the Lord, and logikos.[100] The Christians are to long for something that will cause them to mature in their salvation, but this something, the logikos unadulterated milk, has been variously construed as the Scriptures, the eucharist, or the Lord himself. Before discussing these options, the generic space can now be mapped: partially dependent people are getting rid of obstacles to acquire good input for growth (Figure 7).

Some commentators hesitate to map breast milk directly to the Lord and avoid this by turning the adjectives in the text into nouns: “Car désirer le lait de la Parole de Dieu est goûter le lait savoureux de la bonté de Jésus Christ.”[101] Logikos has become “the word,” and “unadulterated” shifts to “goodness.” There is no need to add these nouns, however. The reference to Lord (kurios) and the play on words with chrēstos—Christos (Christ) make the connection clear, especially when mapping the phrase in the first input space: The missing noun in “assuming you have tasted that the <blank> is fine,” is surely milk. Thus, in the blend, the Lord is the milk of God.[102]

What remains unclear, however, is the meaning of this blend. The reference in verse 3 to Psalm 33 LXX underlines the goodness of God for salvation. But if Peter’s resident aliens (1 Pet 1:1) from the second input space are to “drink” the Lord they have already tasted, in order to grow into salvation, what might that mean? Whereas the broader context of the letter is often brought in to the second input space to provide a mapped element for the milk, I have argued that “Lord” is sufficient for the metaphor. The broader context, however, is needed to unpack the metonymy of dependence on the Lord.[103] For, what does it mean to experience the Lord, or to rely on the Lord for maturity? How, exactly, do the new Christians have access to the Lord?

At this point in the analysis, some of those proposals mentioned above become relevant, not as elements of the second input space to map in the metaphor, but as referents for the metonymy, “the Lord”: does drinking the Lord refer to listening to the Scriptures, taking the eucharist, or something else? The adjective logikos may help since it has not yet been accounted for in this discussion. While it ought not map the milk to the Scriptures since that spot in the structure is taken by “the Lord”, it could possibly explain the metonymy. If logikos points to logos, and if logos refers to the word of God (as it does in 1 Pet 2:8 and 3:1), then perhaps to drink the Lord is to absorb “God’s living and enduring word” (1 Pet 1:23).[104] But I am wary of faux amis.[105]

Troy Martin argues that it is, rather, the eucharist that is referred to as the tasting of the Lord.[106] Following ancient understandings of physiology, he connects the new birth of the Christians to their continuing eucharistic practices: a baby Christian formed by the blood of the Lord, fertilised by the seed of the word of God (1:23–25) could continue to be nourished by the same blood now in the form of the eucharist-as-milk.[107] This structure does neatly map the seed of the father that fertilises the mother’s blood to form first the child, then the milk.[108] However, blood is only mentioned in 1:2 and 1:19 and Christ’s body is not mentioned until 2:24, so Martin’s analysis, while not without foundation, is not directly prompted in the blend. And 1 Peter 1 suggests instead that it is “the sanctification of the Spirit” that combines with the blood of the Lord to bring about the obedience of the Christians (1:2) which is the evidence of their new birth (1:14–16).[109]

Ian W. Scott has conducted an exhaustive study of the meanings of logikos from approximately the 3rd century BCE to the 2nd century CE.[110] His range of meanings includes seven categories: “[t]he substantive for ‘reasoned thought’”; “[d]istinguishing rational beings from irrational animals”; “[d]istinguishing reasoning human beings from irrational people”; “[d]istinguishing the reasoning aspect of the soul from other aspects”; “[o]bjects that consist of, result from, or are employed in reasoning”; “[a]ctivities performed by or guided by reason”; and “[d]istinguishing what is related to discourse in general.”[111] He notes that “[t]o the ancient mind, spoken discourse and reason were often so intertwined as to be indistinguishable,” a comment that relates more broadly to cautions against assuming the same semantic range for a Greek word and its English gloss.[112] To that point, Scott rejects “logical” or “rational” as appropriate glosses because these, in English, can refer to a judgment according to some objective or socially constructed ideas of rationality. Logikos is better glossed as related to “one’s own reasoned deliberation,” or “performed by reasoning,” or simply, “reasoning.”[113]

One text that illustrates both Scott’s meaning of logikos in context and also a different relationship between logikos and logos than a reference to the word of God comes from Plutarch’s Beasts Are Rational. Odysseus is speaking to Gryllus, a Greek whom Circe has turned into a pig:

Odysseus.

…

Do you attribute reason (logikos) even to the sheep and the ass?

Gryllus.

From even these, dearest Odysseus, it is perfectly possible to gather that animals have a natural endowment of reason (logos) and intellect. For just as one tree is not more nor less inanimate than another, but they are all in the same state of insensibility, since none is endowed with soul, in the same way one animal would not be thought to be more sluggish or indocile mentally than another if they did not all possess reason (logos) and intellect to some degree—though some have a greater or less proportion than others. Please note that cases of dullness and stupidity in some animals are demonstrated by the cleverness and sharpness of others—as when you compare an ass and a sheep with a fox or a wolf or a bee. It is like comparing Polyphemus to you or that dunce Coroebusa to your grandfather Autolycus. I scarcely believe that there is such a spread between one animal and another as there is between man and man in the matter of judgement and reasoning (logizomai) and memory. (Plutarch, Moralia. Beasts Are Rational 10.992C–E [Cherniss, Helmbold, LCL]).

This passage illustrates both the use of logos to refer to reason and the use of logikos and logizomai in supporting that discussion.

If Scott is correct, then the milk of God, i.e. the Lord, carries the ability to reason. And since the ancient world understood that a mother’s character was passed on to her children through her milk, so would God’s reasoning character be passed on through the milk which is the Lord.

One last point: some of Scott’s categories relate to a distinction between reasoning and non-reasoning humans, or between reasoning and non-reasoning aspects of the soul. For Philo, as well as for Arius Didymus (1st century BCE), it was the reasoning part of the soul that controlled the passions.[114] Similarly, “reasoning milk” is mentioned in 1 Peter 2:1–3 in the context of an absence of vice. How does this affect the metaphor?

To come back to the blend, the emphasis on the purity of the milk, where “unadulterated” in 2:2 maps onto the absence of the vices listed in 2:1 (see also 4:3–4) compresses clothing and impurities together as obstacles to access good milk. Thus, the vices in the second input space entail an unfit wet nurse producing “alien and degenerate” milk in the first input space (not in figure).[115] Drinking adulterated milk maps onto obedience to former desires (1:14–16).[116] So, in order to grow, infants need access to pure milk which they recognise by taste. Similarly, Christians grow into salvation as their continued access to the Lord’s reasoning allows them to remove vices from their lives.[117]

While several basic metaphors ground this blend including IDEAS ARE FOOD, the most emphasised are DESIRE IS HUNGER, MORAL GROWTH IS PHYSICAL GROWTH, and MORALITY IS PURITY.[118] The vice list and the reference to unadulterated milk also imply the existence of the opposite of that last: IMMORALITY IS IMPURITY. I find DESIRE IS HUNGER particularly interesting. While hunger arises spontaneously in infants, the author of 1 Peter tells his addressees that they should desire the Lord. The compression of helplessness with agency mentioned at the beginning of this section can be found even at the root of the metaphor. The giving of agency would be important for those suffering oppression.[119]

The social identity of this community is being formed by the knowledge of vices they are expected to abandon. They also are being asked to evaluate their own desire for the Lord, particularly his reasoning as put forth by the letter as a whole (e.g., 2:13–3:22). This evaluation of themselves with regard to their emotional commitment to the priority of the group will, if responded to positively, help to weaken their previous commitments to other identities and become more conformed to the ideal of the group.[120]

Conclusion

This paper demonstrates the variety of ways nursing metaphors are used in canonical texts as well as the helpfulness of cognitive mapping for unpacking each use. Cognitive metaphor theory has provided the tools to take apart the workings of the four nursing metaphors in the New Testament. While all four rely on IDEAS ARE FOOD as a basic ground for setting up the blend, each passage then focuses on a different cognitive aspect of the nursing frame. Based on the SOCIAL GROUP IS A FAMILY, 1 Thessalonians 2:7 focuses its blend on the love and self-sacrifice of Mother Paul (and his companions). For 1 Corinthians 3:1–3, the blend ONGOING CAUSATION IS NOURISHING in the context of the expectation that character is passed through milk put the onus on the Corinthians to make better choices about where they are getting their information for the sake of the health of their community (SOCIAL FUNCTIONING IS PHYSICAL HEALTH). Hebrews 5:11–14 sets up a metaphor that is then contradicted by another metaphor in Heb 6:7–8. The blend MORAL GROWTH IS PHYSICAL GROWTH allows the author to make clear that a lack of moral growth will not be tolerated in God’s family. Finally, in 1 Peter 2:1–3, DESIRE IS HUNGER comes to the fore. While the contents of the teaching is important, and the author mentions behaviours to avoid, the metaphor in this passage renews the Christians’ desire for and dependence on the reasoning of the Lord for their community. The parsing of each of these metaphors into their component parts reveals the unique configuration of each. And while this article has focused on CMT, each metaphor also worked to enhance the social identity of its auditors by communicating cognitive content, by prompting heightened emotions, and by enhancing their self-evaluation as part of the ingroup.

Bibliography

Alkier, Stefan. “New Testament Studies on the Basis of Categorical Semiotics.” Pages 223–48 in Reading the Bible Intertextually. Edited by Richard B. Hays, Stefan Alkier, and Leroy A Huizenga. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2009.

Ascough, Richard S. 1 and 2 Thessalonians: Encountering the Christ Group at Thessalonike. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014.

Attridge, Harold W. The Epistle to the Hebrews: A Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress, 1989.

Bartchy, S. Scott “Who Should Be Called Father? Paul of Tarsus between the Jesus Tradition and Patria Potestas.” Biblical Theology Bulletin: Journal of Bible and Culture 33 (2003): 135–47. doi:10.1177/014610790303300403

Ben-Porat, Ziva. “The Poetics of Literary Allusion.” PTL: A Journal for Descriptive Poetics and Theory of Literature 1 (1976): 105–128.

Best, Ernest. The First and Second Epistles to the Thessalonians. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1986.

Boring, M. Eugene. I & II Thessalonians: A Commentary. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2015.

Buchanan, George Wesley. To the Hebrews: Translation, Comment and Conclusions. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1972.

Burke, Trevor J. Family Matters: A Socio-Historical Study of Fictive Kinship Metaphors in 1 Thessalonians. London: T&T Clark International, 2003.

Collins, Raymond. First Corinthians. SP 7. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 1999.

Dahl, N. A. Studies in Paul: Theology for the Early Christian Mission. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2002.

Dancygier, Barbara and Eve Sweetser. Figurative Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Dasen, Véronique. “Childbirth and Infancy in Greek and Roman Antiquity.” Pages 291–314 in A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Edited by Beryl Rawson. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2011.

Dasen, Véronique. “Des nourrices grecques à Rome.” Paedagogica Historica 46 (2010): 699–713. doi:10.1080/00309230.2010.526330

Davis, Phillip A., Jr. The Place of Paideia in Hebrews’ Moral Thought. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2018.

Dekker, Jaap. Zion’s Rock-Solid Foundations: An Exegetical Study of the Zion Text in Isaiah 28:16. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

deSilva, David A. Perseverance in Gratitude: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on the Epistle “to the Hebrews.” Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans 2000.

Donelson, Lewis R. I & II Peter and Jude: A Commentary. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Donfried, Karl P. “The Epistolary and Rhetorical Context of 1 Thessalonians 2:1–12.” Pages 31–60 in The Thessalonians Debate: Methodological Discord or Methodological Synthesis? Edited by Karl P. Donfried and Johannes Beutler. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000.

Easter, Matthew C. Faith and the Faithfulness of Jesus in Hebrews. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Eco, Umberto. Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Elliott, John H. First Peter: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New York, NY: Doubleday, 2000.

Emerton, John A. “Some Difficult Words in Isaiah 28.10 and 13.” Pages 39–56 in Biblical Hebrew, Biblical Texts: Essays in Memory of Michael P. Weitzman. Edited by Ada Rapoport-Albert and Gillian Greenberg.Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 2001.

Esler, Philip F. “An Outline of Social Identity Theory.” Pages 13–39 in T&T Clark Handbook to Social Identity in the New Testament. Edited by J. Brian Tucker, et al. London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Fauconnier, Gilles and Mark Turner. The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2002.

Francis, James M. M. “‘As Babes in Christ’: Some Proposals Regarding 1 Corinthians 3:1-3.” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 2 (1980): 41–60. doi:10.1177/0142064X8000200703

Furnish, Victor Paul. 1 Thessalonians, 2 Thessalonians. Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2007.

Gaventa, Beverly Roberts. “Apostles as Babes and Nurses in 1 Thessalonians 2:7.” Pages 193–207 in Faith and History in the New Testament: Essays in Honor of Paul W. Meyer. Edited by John T. Carroll, Charles H. Cosgrove, and E. Elizabeth Johnson. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1991.

Gaventa, Beverly Roberts. “Our Mother St. Paul: Toward the Recovery of a Neglected Theme.” Princeton Seminary Bulletin 17 (1996): 29–44.

Gillman, John. “Paul’s ΕΙΣΔΟΔΟΣ: The Proclaimed and the Proclaimer (1 Thes 2,8).” Pages 62–70 in Thessalonian Correspondence. Edited by Raymond F. Collins. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium. Louvain: Leuven University Press, 1990.

Goodrich, John. Paul as an Administrator of God in 1 Corinthians. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Hays, Christopher B. “The Covenant with Mut: A New Interpretation of Isaiah 28:1–22.” Vetus Testamentum 60 (2010): 212–40. doi:10.1163/156853310X486857

Heil, John Paul. Hebrews: Chiastic Structures and Audience Response. Washington, DC: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2010.

Hooker, Morna D. “Christ, the ‘End’ of the Cult.” Pages 189–212 in The Epistle to the Hebrews and Christian Theology. Edited by Richard Bauckham, et al. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2009.

Hooker, Morna D. “Hard Sayings: I Corinthians 3:2.” Theology 69 (1966): 19–22. doi:10.1177/0040571X6606954705

Hoppin, Ruth. “Priscilla and Plausibility: Responding to Questions about Priscilla as Author of Hebrews.” Priscilla Papers 25 (2011): 26–28.

Horsley, Richard A. “How Can Some of You Say That There Is No Resurrection of the Dead: Spiritual Elitism in Corinth.” Novum Testamentum 20 (1978): 203–231. doi:10.1163/156853678X00092

Hunt, Laura J. “1 Peter.” Pages 527–42 in T & T Clark Social Identity Commentary on the New Testament. Edited by J. Brian Tucker and Aaron Kuecker. London: T & T Clark, 2020.

Hunt, Laura J. Jesus Caesar: A Roman Reading of the Johannine Trial Narrative. WUNT II 506. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2019.

Jobes, Karen H. 1 Peter. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2005.

Jobes, Karen H. “Got Milk? Septuagint Psalm 33 and the Interpretation of 1 Peter 2:1–3.” Westminster Theological Journal 63 (2002): 1–14.

Johnson, Luke Timothy. Hebrews: A Commentary. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2012.

Keener, Craig S. 1–2 Corinthians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Keener, Craig S. 1 Peter: A Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2021.

Koester, Craig R. Hebrews: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New York, NY: Doubleday, 2001.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Lee, Mireille. “Constru(Ct)Ing Gender in the Feminine Greek Peplos.” Pages 55–64 in The Clothed Body in the Ancient World. Edited Liza Cleland, Mary Harlow, and Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2005.

Malherbe, Abraham J. “‘Gentle as a Nurse’: The Cynic Background to 1 Thess 2.” Novum Testamentum 12 (1970): 203–217. doi:10.1163/156853670X00243

Martin, Troy W. “Christians as Babies: Metaphorical Reality in 1 Peter.” Pages 99–134 in Reading 1–2 Peter and Jude. Edited by Eric F. Mason and Troy W. Martin. Atlanta, GA: SBL, 2014.

McNeel, Jennifer Houston. Paul as Infant and Nursing Mother. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2014.

Menken, M. J. J. and Steve Moyise. Isaiah in the New Testament: The New Testament and the Scriptures of Israel. London: T&T Clark, 2005.

Michaels, J. Ramsey. 1 Peter. Waco, TX: Word, 1988.

Míguez, Néstor. The Practice of Hope: Ideology and Intention in First Thessalonians. Trans. Aquíles Martínez. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2012.

Nagel, Peter. “1 Corinthians 14:21—Paul’s Reflection on Γλωσσα.” Journal of Early Christian History 3 (2013): 33–49. doi:10.1080/2222582X.2013.11877274

Neil, William. The Epistle of Paul to the Thessalonians. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1950.

O’Reilly, Matthew P. “1 Thessalonians.” Pages 421–33 in T&T Clark Social Identity Commentary on the New Testament. Edited by J. Brian Tucker and Aaron Kuecker. London: Bloomsbury, 2020.

Osborne, Grant R. 1 & 2 Thessalonians: Verse by Verse. Bellingham, WA: Lexham, 2018.

Palmer, Darryl W. “Thanksgiving, Self-Defence, and Exhortation in 1 Thessalonians 1–3.” Colloqium 14 (1981): 23–31.

Penniman, John David. Raised on Christian Milk: Food and the Formation of the Soul in Early Christianity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017.

Perkins, Pheme. First Corinthians. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012.

Puig Tàrrech, Armand. “Le milieu de la première épître de Pierre.” Revista Catalana de Teologia 5 (1980): 331–402.

Rice, Gene. “Isaiah 28:1–22 and the New English Bible.” Journal of Religious Thought 30 (Fall 1973): 13–17.

Sanders, John. Theology in the Flesh: How embodiment and Culture Shape the Way We Think about Truth, Morality, and God. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2016.

Scott, Ian W. “‘Your Reasoning Worship’: Λογικός in Romans 12:1 and Paul’s Ethics of Rational Deliberation.” The Journal of Theological Studies69 (2018): 500–32. doi:10.1093/jts/fly117

Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990.

Sparreboom, Anna “Wet-Nursing in the Roman Empire: Indifference, Efficiency and Affection.” MPhil. Free University Amsterdam, 2009.

Thiselton, Anthony C. The First Epistle to the Corinthians: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000.

Thompson, James W. Hebrews. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2008.

Tite, Philip L. “Nurslings, Milk and Moral Development in the Greco-Roman Context: A Reappraisal of the Paraenetic Utilization of Metaphor in 1 Peter 2.1–3.” Journal for the Study of the New Testament31 (2009): 371–400. doi:10.1177/0142064X09104957

Tucker, J. Brian. “You Belong to Christ”: Paul and the Formation of Social Identity in 1 Corinthians 1–4. Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2010.

Wanamaker, Charles A. The Epistles to the Thessalonians: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990.

Weima, Jeffrey A. D. 1–2 Thessalonians. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2014.

Weima, Jeffrey A. D. “‘But We Became Infants among You’: The Case for Νηπιοι in 1 Thess 2.7.” New Testament Studies 46 (2000): 547–64. doi:10.1017/S0028688500000321

Westfall, Cynthia Long. A Discourse Analysis of the Letter to the Hebrews: The Relationship between Form and Meaning. London: T & T Clark, 2005.

White, Adam G. Where Is the Wise Man?: Graeco-Roman Education as a Background to the Divisions in 1 Corinthians 1–4. London: T&T Clark, 2015.

Willis, Wendell. “The ‘Mind of Christ’ in 1 Corinthians 2,16.” Biblica 70 (1989): 110–22.

Witherington, Ben, III. Conflict and Community in Corinth: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on 1 and 2 Corinthians, Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans 1995.

Witherington, Ben, III. Letters and Homilies for Jewish Christians: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on Hebrews, James and Jude. Westmont: IVP Academic, 2010.

Zuiddam, Benno A. “Die eerste beginsels van die woord, die implikasie van Heb 5:12 vir kerk en teologie.” Scriptura: International Journal of Bible, Religion, and Theology in Southern Africa 108 (2011): 238–48. doi:10.7833/107-0-139

[1] George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 270.

[2] John Sanders, Theology in the Flesh: How embodiment and Culture Shape the Way We Think about Truth, Morality, and God (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2016),20–23: Barbara Dancygier and Eve Sweetser, Figurative Language (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 25. For more on Neural Theory, see Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors, 254–59.

[3] Dancygier and Sweetser, Figurative Language, 25 and ICSI Metanet Metaphor Wiki (tinyurl.com/2y6p7acz).

[4] John David Penniman, Raised on Christian Milk: Food and the Formation of the Soul in Early Christianity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017), 8. Note that Penniman defines paideia as “the constellation of social ideologies, medical traditions, and educational and curricular standards that contributed to the proper formation of the human person … [t]ypically reserved only for the elite” (6–7).

[5] Philip F. Esler, “An Outline of Social Identity Theory,” in T&T Clark Handbook to Social Identity in the New Testament, edited by J. Brian Tucker, et al. (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), 13–39.

[6] Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2002), 35–36, 40–50, 293. Note that for the sake of simplifying the terminology, I have identified the relations that constrain the blends as they arise in the discussion but not the type of network being used (simplex, mirror, single- or multiple-scope).

[7] The building metaphor is admittedly imperfect but will hopefully be helpful to those unfamiliar with this material.

[8] Dancygier and Sweetser, Figurative Language, 18. A domain is similar: a general aggregate of concepts and symbols clustered around a topic. Frames, however, add a cognitive structure that organises part or all of the domain. Note that the boundaries of domains and frames are fuzzy and can be creatively extended.

[9] Author translations unless otherwise noted. In this case, William Neil suggested “toil and moil” to get at the assonance of the Greek in verse 9; William Neil, The Epistle of Paul to the Thessalonians (New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1950), 40–41.

[10] For an example of a contract, see BGU 1107. Note that although Dasen suggests that trophos designates a dry nurse, with titthē more properly used for a wet nurse, evidence from a broad swath of time shows that trophos was used for a wet nurse as well (Hippocrates of Cos, De morbis 4.24; Nonnas, Dionysiaca 9.220–23, 302–311); Véronique Dasen, “Des nourrices grecques à Rome,” Paedagogica Historica 46.6 (2010): 700. doi:10.1080/00309230.2010.526330

[11] M. Eugene Boring, I & II Thessalonians: A Commentary (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2015), 87; Jeffrey A. D. Weima, 1–2 Thessalonians (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2014), 147; Richard S. Ascough, 1 and 2 Thessalonians: Encountering the Christ Group at Thessalonike (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 36; Karl P. Donfried, “The Epistolary and Rhetorical Context of 1 Thessalonians 2:1–12,” in The Thessalonians Debate: Methodological Discord or Methodological Synthesis?, edited by Karl P. Donfried and Johannes Beutler (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000), 52.

[12] Space does not allow me to discuss the assumptions about a wet nurse’s feelings made by the elite in contrast to the true feelings of at least some wet nurses whose affections must be performed, genuine or not, for their own physical and economic security. Some relevant references on the topic of affection both genuine and performed include Beverly Roberts Gaventa, “Apostles as Babes and Nurses in 1 Thessalonians 2:7,” in Faith and History in the New Testament: Essays in Honor of Paul W. Meyer, edited by John T. Carroll, Charles H. Cosgrove, and E. Elizabeth Johnson (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1991), 201; Abraham J. Malherbe, “‘Gentle as a Nurse’: The Cynic Background to 1 Thess 2,” Novum Testamentum 12(1970): 211. doi:10.1163/156853670X00243; Anna Sparreboom, “Wet-Nursing in the Roman Empire: Indifference, Efficiency and Affection” (MPhil, Free University Amsterdam, 2009), 37–38, 44–48; Jennifer Houston McNeel, Paul as Infant and Nursing Mother (Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2014), 77–80; James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990), 28–36, 86–87.

[13] Although Philo’s discussion is generally focused on suckling animals (Lev 22:27), he eventually uses the word mastos (breast), which LSJ suggests is rarely used of animals. That he has moved into addressing human behaviour is made especially likely because he begins a lyric description of milk as nature’s gift for infants (130) and then continues by berating parents who kill or abandon their newborns (131–34), arguing that if God intends for newborn animals to suckle, much more should a human mother not be separated from her child. The pain of a mother who is unable to nurse also features prominently in the story of Romulus and Remus, although in this case it is a she-wolf substituting for the woman (Plutarch, Moralia 320 D, On the Fortune of the Romans 8).

[14] For a more detailed description of this understanding, as well as further discussion on Favorinus, see Philip L. Tite, “Nurslings, Milk and Moral Development in the Greco-Roman Context: A Reappraisal of the Paraenetic Utilization of Metaphor in 1 Peter 2.1–3,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament3 (2009): 382–84, cf. 389, doi:10.1177/0142064X09104957; Dasen, “Des nourrices,” 701–703, 706.

[15] I follow Weima for the variant reading here; Jeffrey A. D. Weima, “‘But We Became Infants among You’: The Case for Νηπιοι in 1 Thess 2.7,” New Testament Studies 46 (2000): esp. 554–560. doi:10.1017/S0028688500000321

[16] Weima, Thessalonians, 138.

[17] Ascough, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, 36–37.

[18] Ernest Best, The First and Second Epistles to the Thessalonians (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1986), 99–101; so, too, Neil, Thessalonians, 39.

[19] Darryl W. Palmer, “Thanksgiving, Self-Defence, and Exhortation in 1 Thessalonians 1–3,” Colloqium 14 (1981): 25–26.

[20] Victor Paul Furnish, 1 Thessalonians, 2 Thessalonians (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2007), 56; John Gillman, “Paul’s ΕΙΣΔΟΔΟΣ: The Proclaimed and the Proclaimer (1 Thes 2,8),” in Thessalonian Correspondence, edited by Raymond F. Collins, Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium (Louvain: Leuven University Press, 1990), 64.

[21] Compressions allow metaphors to bring large or complex concepts down to “human scale”; Dancygier and Sweetser, Figurative Language, 84–96; McNeel, Paul as Infant, 8 n. 26; Grant R. Osborne, 1 & 2 Thessalonians: Verse by Verse (Bellingham, WA: Lexham, 2018), 42.

[22] Fauconnier and Turner, The Way We Think, 98.

[23] McNeel, Paul as Infant, 59, 134.

[24] Furnish, Thessalonians, 60; Osborne, Thessalonians, 45. The following scholars connect verse 9 with the preceding material; however, for the most part they do not recognise the continuation of the nursing metaphor: Boring, Thessalonians, 88; Weima, Thessalonians, 149; Best, Thessalonians, 103; Charles A. Wanamaker, The Epistles to the Thessalonians: A Commentary on the Greek Text (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990), 102; Neil, Thessalonians, 40.

[25] Both Boring and Neil helpfully envision a fluidity between Paul’s work and preaching quite different from our contemporary experiences; Boring, Thessalonians, 88; Neil, Thessalonians, 41.

[26] Note that as mentioned, above, the virtue of the mother would be passed on through her milk. This relation is not referenced by the passage in either input space, so it should not be carried into the blend, although some auditors might have drawn that conclusion from the reading of the passage.

[27] McNeel, Paul as Infant, 103–104, 136–37; Trevor J. Burke, Family Matters: A Socio-Historical Study of Fictive Kinship Metaphors in 1 Thessalonians (London: T&T Clark International, 2003), 153–54.

[28] Dancygier and Sweetser, Figurative Language, 25.

[29] Néstor Míguez, The Practice of Hope: Ideology and Intention in First Thessalonians, trans. Aquíles Martínez (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2012), 99, emphasis original.

[30] Penniman, Raised on Christian Milk, 16. See also the continuing influence of nurses on their charges; Dasen, “Des nourrices,” 709–712.

[31] Penniman, Raised on Christian Milk, 50–51. Note that in this blend, women are not necessary for the provision of the gospel, bringing love and joy (1 Thessalonians 1:3, 6; 3:12).

[32] McNeel, Paul as Infant, 134–135.

[33] Cf. Míguez, The Practice of Hope, 101. For self-categorisation theory, an important aspect of social identity, see Esler, “An Outline of Social Identity Theory,” 22–26. For more on social identity in 1 Thessalonians, see Matthew P. O’Reilly, “1 Thessalonians,” in T&T Clark Social Identity Commentary on the New Testament, edited by J. Brian Tucker and Aaron Kuecker (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 422–33.

[34] I have chosen “fleshy” and “fleshly” as glosses that reproduce a closeness in sounds similar to that between sarkinos and sarkikos.

[35] Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors, 260–61.

[36] James M. M. Francis, “‘As Babes in Christ’: Some Proposals Regarding 1 Corinthians 3:1-3,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 2.7 (1980): 43.doi:10.1177/0142064X8000200703

[37] Anthony C. Thiselton, The First Epistle to the Corinthians: A Commentary on the Greek Text (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000), 289.

[38] Penniman, Raised on Christian Milk, 74.

[39] John Goodrich, Paul as an Administrator of God in 1 Corinthians (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 128–29.

[40] “But seeing that for babes milk is food, but for grown men wheaten bread, there must also be soul-nourishment, such as is milk-like suited to the time of childhood, in the shape of the preliminary stages of school-learning, and such as is adapted to grown men in the shape of instructions leading the way through wisdom and temperance and all virtue. For these when sown and planted in the mind will produce most beneficial fruits, namely fair and praiseworthy conduct. By means of this husbandry whatever trees of passions or vices have sprung up and grown tall, bearing mischief-dealing fruits, are cut down and cleared away, no minute portion even being allowed to survive, as the germ of new growths of sins to spring up later on” (Philo, De agricultura 2.9–10 [Colson, Whitaker, LCL]). Cf. Pheme Perkins, First Corinthians (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 72–73.

[41] Wendell Willis, “The ‘Mind of Christ’ in 1 Corinthians 2,16” Biblica 70 (1989): 113; J. Brian Tucker, “You Belong to Christ”: Paul and the Formation of Social Identity in 1 Corinthians 1–4 (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2010), 184–87.

[42] Thiselton, Corinthians, 292.

[43] Francis, “As Babes in Christ,” 43.

[44] Thiselton, Corinthians, 288–89. Thiselton calls this “moved by entirely human drives” and understands sarkikos as “moved by self-interest.” While I agree, I have reworded the same idea to avoid confusion with Paul’s characterisation of sarkikos as “according to human standards” (v. 3) (which Thiselton mentions), but also to recognise that the Corinthians were not previously without gods.

[45] N. A. Dahl, Studies in Paul: Theology for the Early Christian Mission (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2002), 48; Morna D. Hooker, “Hard Sayings: I Corinthians 3:2,” Theology 69, no. 547 (1966): 21–22. doi:10.1177/0040571X6606954705; Ben Witherington, III, Conflict and Community in Corinth: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on 1 and 2 Corinthians (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans 1995), 131–32; Thiselton, Corinthians, 292–93.

[46] Dancygier and Sweetser, Figurative Language, 74.